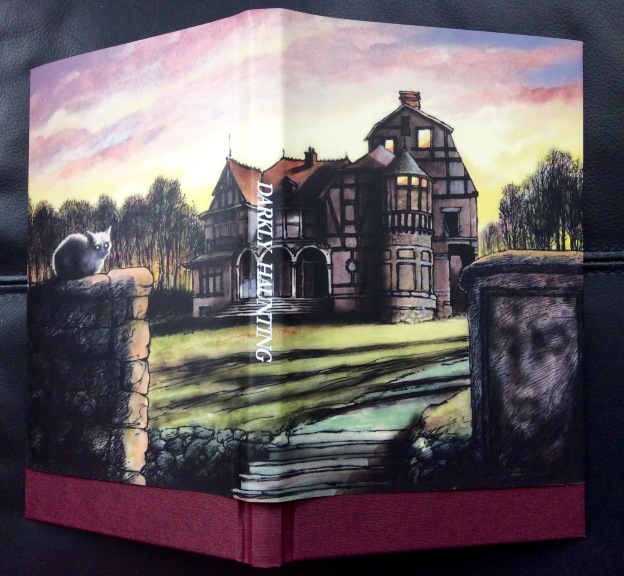

Darkly Haunting

SAROB PRESS 2017

Stories by James Doig, Colin Insole, Rhys Hughes, Peter Holman, D.P. Watt.

Edited by Robert Morgan

My previous reviews of this publisher HERE

I shll be reviewing this book in a few weeks and, when I do, my thoughts will appear in the comment stream below…

“, and in the exaggerated lens of nightmare…”

At first, I was worried this would be too traditional for my tastes, even if it is an adequately accomplished sense of a place, a tragic event and a haunting, and it is. But it gradually took a decided grip on me, the ‘found’-telling by gent to gent in civilised trappings of actually being brought to come there and then the trappings of cordial whiskey, and all this is true, but there is also a strong sense of Norfolk, its stretching back to the Middle Ages, its follies around a large house, the faltering sense of scions and their heritage, the fallibility of lineage and intention, the Christian mythos that underlies us all on this side of England by the North Sea, the ‘early stages’ and ‘chosen fragments’ of Medieval and Elizabethan drama, the early BBC radio documentaries that I recall, and wonderful reel to reel tape recorders, and, yes, that lens of nightmare that this polished text successfully manages to wield.

“It was his land of lost content.”

A land of the past – in rapturous rapport with Fournier’s Grand Meaulnes – with Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock – with H.E. Bates’ nature and war – with the shoals of the dead from Elizabeth Bowen’s blitzed London …. but this is Colin Insole supreme, and those hasty rapports of mine are to just give a hint as to this monumental and momentous work of fiction that is uniquely in-soul. Nobody can really describe this series of cross-sections of Proustian time, as told from various points of view, flirtations as flirtations and flirtations with death, and a recurrent unrequited love circling the cricket field of England’s past pastures and linked railtrack halts or junctions, now a lost domain. The two wars of the 20th century, and those doomed and those still living by haunting each other as told by matchless unforgettable prose with embedded items of verse and resplendent tropes of emotion. This is a genuine classic work to go with Insole’s other fictions (long among my handful of favourite writers), particularly with his other wartime rhapsody of lost time: ‘The Hill of Cinders.’

I can only be grateful I lived long enough to read another Insole work, thanks to this book. This is his newest classic, if not THE Insole classic, even or especially with its haw haws, and its tough cheddar, old cock.

“And she marvelled at how the living and the dead lay down to sleep and rest together, and how their dreams must merge and blur.”

“I just wanted to rebel against insignificance.”

Two consecutive stories in this book where two of my handful of favourite writers appear to produce their potential life classic to date. Both stories with a cricket match. This substantive story is, for me, the culmination of what I have been expecting from Rhys Hughes for over twenty years of reading him (see my reviews in the above by-line link.) It is a work that is recognisably RhysHughesian but with no self-referential authorial metafictions nor constructively child-like items of wordplay. However, there are still many brilliant inbuilt conceits. A story of Colin who is a person himself distinct from the author but with perceived Rhysian autobiographical elements (like a beach party and a dancing club.) It is the telling treatment of someone’s life, its ambitions and its nagging sense of dissatisfaction here in the shape of a recurrently haunting black dog (almost, for me, a kindred spirit of Churchill’s ‘black dog’ syndrome), a beast that turns up every ten years upon each Birthday-Eve’s turn of the numbers of Colin’s age towards something-zero. This is amazingly strong material that will set you thinking, make you reassess your own life, a phenomenon, for me, allied with Zeno’s Paradox. Here Zero’s Paradox? Some strongly depicted characters, too, in his life. And visionary concerns with, say, a snowy avalanche and a cellar trap, plus hair-trigger moments that seem to last forever. The ending is genius.

A telling tale for me personally as I wait patiently for the turning from 69 to 70.

This is major unmissable stuff. No mistake.

“Islanders that end in rebellion (8).”

A very well-characterised, well-written and compellingly believable portrait of an elderly ex serviceman and his friend from the old days, having served in the Irish Troubles of the 1970s, now beset by a haunting paranoia of being pursued by individuals from that past. Including being ambushed in one of today’s supermarkets. Some beautiful turns of phrase: “a face like a clenched fist”, “moping around in a black dress with her hair scraped back like she was dead already.”

A sense of either senile dementia or a retrieved reality as a sign that modernity no long engages him as much as reading John Buchan books once did, and his need to go back to the past even if that past has more dangers to his body if not to his soul.

Loved that Buchan novel serialised on TV in the 1950s.

If Brexit happens, we shall be required to hang famous European paintings upside down. (A quote from a review a few weeks ago.)

Now for what was found in the Ballet Case…

“, like I was in a cupboard while Europe falls apart…”

In some ways, a post-Brexit SF story depicting the foul and fell repercussions some 30 years hence, without using the word Brexit at all.

In another way, an extension of this book’s nostalgia gent-to-gent over cordial whisky factored into by the thwarted ambitions of Hughes in the form of a recurrent Zeno’s Paradox, the haunting of them like the past wars in Holman, then Insole’s cross-sections of war and Meaulnes-type literature and Fern Hill or H.E. Bates type gaia, growing into more of this book’s nagging or sometimes gossamer gestalt.

But in essence, this is a work-on-its-own, a mesmerising tryst with the oblique power of fantasy that is generously dream-like or Sarban-like, even Blakean or Carcosan (a King in a yellow robe) so as to conjure the past and the future’s attempts to transcend it. Despite the strictures of historic Brexit, Englishman Michael lives in Dinan, in a house overlooking the mysterious, seemingly untenanted, ironically-named Maison Anglaise, a vaguely perceived house that seems to haunt him (following the telling departure of his visiting, whisky-sharing old friend David), and somehow, based on the evidence of the diary in his daughter’s Ballet Case, haunting her with its lasting, literally long-standing visions, and his wife, too. It will be hard to forget this moving and gradually grasping work. We shall all need to stand and wait.

————————-

“In the pebbles of the holy streams.”

Fern Hill, Dylan Thomas

end