Best British Short Stories 2012

Series editor NICHOLAS ROYLE

(My previous reviews of this writer are linked from HERE)

SALT PUBLISHING

(My previous reviews of this publisher are HERE)

Featuring stories by: Socrates Adams, AK Benedict, Neil Campbell, Ramsey Campbell, Stella Duffy, Julian Gough, Joel Lane, Stuart Evers, Will Self, Michael Marshall Smith, Alison MacLeod, Dan Powell, Jo Lloyd, HP Tinker, Robert Shearman, Jaki McCarrick, Jonathan Trigell, Emma Jane Unsworth, Jeanette Winterson.

I hope to gestalt real-time review this book over the next few months in the comment stream below…

where it was the last story!

================================

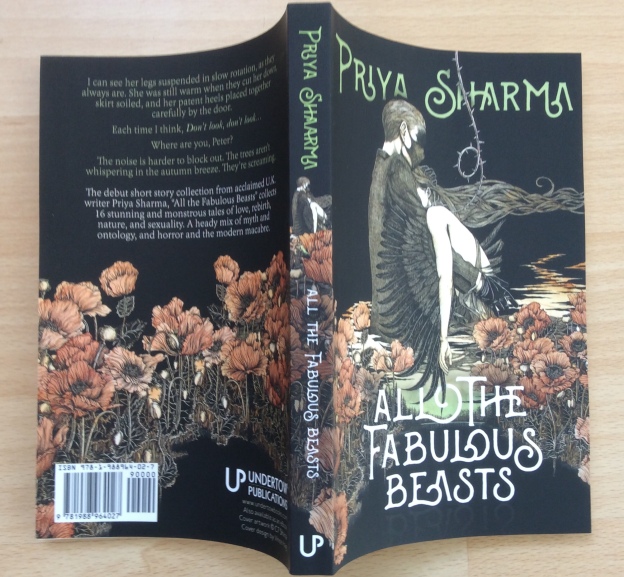

The Crow Palace

“That’s where I found her, a jay perched on her back. It looked like it had pushed her in. That day the crow palace had been covered with carrion crows; bruisers whose shiny eyes were full of plots.”

Full of plots, say, from the Malik and Littlewood, the choosing between chicks, whether up or down, or, as here, in or under? The counted Corvids of McGuire and the absorbing or being absorbed of O’Driscoll.

This story about twin sisters, one special needs through physical illness, like Littlewood’s underchick. And McGuire’s. The death of the sisters’ mother, quoted above. And now the story’s story proper, the death of their Dad, when the sisters are older and at least one of them tellingly greyer. The funeral guests. And the story being built from the past and what may have happened. The business-like narrator is the healthy sister-chick and has to endure the unwanted clinging of her boy friend whom she then ditches by phone, whilst later she is given Llewellyn’s version of hedonistic erotic (tantamount to mindless) penetration in the garden by someone from the funeral, happening near the Crow Palace, that structure Dad built for the birds. The other, the special sister, still oblique. We gather more about them both before they do themselves…. the whole backstory seemingly given to us, but, for me, with the seemingly reliable narrator, as in the O’Driscoll, now as unreliable or, even, maddened as you need her to be to reconcile truth with fiction: as to which is which chick? Even who the narrator and whom the narrated? (The word ‘chick’ used as in the Littlewood story.) And finally who is impregnated and with what, eventually to hatch and fly?

“Coins and bottle tops. Odd earrings. Screws. Watch parts. The tiny bones of rodents, picked clean and bleached by time. I used to have a collection of my own, the crows left us treasures on the crow palace in return for food.”

And there are many other such lists in this work. In this book, too. Lists and connections, some more real than they at first seem, whether intended or not. Keys and secrets. With a tutelary bird’s nurturing wings around this book, enabling those within it to hatch, then to fly as one.

“I know there’s more chance that the Liver birds will fly than of me leaving here.”

From the earlier birds above with black feathers, here I visit a para-Liverpool in a way that my cat’s meat man Blasphemy Fitzworth worked the streets of Victorian London. Here it’s Tom with cry of “Ra Bon! Ra Bon!” amid recognisable scousers, even the Philharmonic pub I visited in recent years. Trans-time Tom it achronically seems, other bodily things, too, perhaps. Here the Liver in Liver birds, is one of such items as the liver itself or kidney or piece of skin that the Peels want for nefarious or queer medicine amid riot threats and trade disputes and oppression of the fleshy masses. Tom is such a contracted carrier, and the plots and machinations are addictive reading, making you feel you can’t leave, here, too. At least in one piece. A language to match, cloying but thrill narrative. A rat gnawing your toes. A Priya story that might say to itself: “Oh, to wield so much power that you don’t have to exert it.” Meanwhile, I am on the side of the masses.

“A game of Rock, Paper, Scissors was frank porn.”

A story obsessed with perfect hands as erogenous, and their flensing. Ultimately shocking, but seasoned with codes of remembering the parts of the hands in human biology – as well as in palmistry, always a mystery. Or is Sam more obsessed that even the story itself pertains? It’s just that match-making – like bringing a sister along to meet someone at a dinner party – actually takes on a new meaning here within even a smaller group! Begs some questions, though, that will delightfully nag at you. And relates tellingly to the previous story’s hints of grafting after trading parts. But I was particularly impressed by the plot’s earlier obliquely subtle signalling of the later plot by reference to the ‘Richard of York’ mnemonic bringing colour to the woman’s face. (My boyhood version of that mnemonic was always ‘ROY Got Bashed In Vienna.’)

“I read her Machiavelli and Chomsky; I play her Debussy and Chopin.”

Debussy died 100 years ago today. Also today’s the birthday of my late father. Debussy composed a piece called Syrinx that my son has often played on the flute. Syrinx somehow seems appropriate to this story, fusing more than one of its meanings. It is a sad story. I was highly moved by it. It tells of woman suffering from endometriosis (a condition that has blighted the life somewhat of someone else in my family) and she seeks ways and means of motherhood. I do not wish to further adumbrate her methods and the result. Or her daughter’s wishbone and the decision to be made about it. It is seriously charged material. I was thankfully and significantly inspired by the story’s ending, however. A landmark read for me. Fiction made religion, although somewhere in the story, I recall, there is an ironic mention of religion made fiction!

==============================

“…sheltering in his groin.”

I was wondering why I feel urged to find a gestalt or a meaning beyond meaning – and indeed this story of a nuclear one child family involving the touching treatment of the death of the husband and then the arrival of some Jack ‘beanstalk’ sunflower monster from the seeds he left behind is genuinely frightening as a straight horror tale and, if you can actually envision it happening, even more frightening. But then I thought of Pip the wife as a sort of seed name, the sunflower seeds, and the seeds around the testicles and then the very thought of the biblical umbilical ‘child’, the crow, the mule, the pig from the previous texts, and it becomes even even even more frightening by implication.

==============================

“Nothing in this world fits together quite right.” (24 Apr 12 – 8.25 pm bst)

The Ballad of Boomtown – Priya Sharma

“I stand on the threshold of the past.”

On this very day, the UK has officially entered a double-dip recession: and Adam Smith (once author of ‘The Wealth of Nations’) resigns his position so as to create a political firebreak. And this story is a symptom of our era’s enduring financial f**kbubble: here now taken literally as a bubble crime of both passion and omission, a crime that brings down retribution upon the story’s female protagonist even from those mythic beings (The Three Sisters) who should support her. With which I feel emotional empathy. Like the first story, we have roots to and as well as from the past, turning ‘pastilential’ just as human motives and yearnings are subsumed by entropy. But where does entropy start, when does it end? Towards another ‘cold sore’-type of facial condition from the first story, & we are stirred by the effective prose that has its own roots in the paper on which the text is stained like tiny articulate shadows. Here we truly inhale shadows. In the previous two stories, shadows inhaled shadows, perhaps. Then a bird, now an owl or horse. Although humanity always reaches the ultimate endgame of encroaching amnesia, myths exploit a special athanasy. The Three Sisters. And tantamount to a type of Lady Macbeth, our heroine inhales the sorrow that always follows a false certainty. A debt crisis of the soul. Like starting to build a housing estate in the more positive sectors of a cycle only to be aborted by the boom’s busting…here evocatively conveyed. And she will herself be turned to stone, no doubt, rooted to the earth’s core: potentially becoming her own myth: a myth towards which future women might return or seek out again and again through each feminine cycle of existence, an existence that is actually created by means of the thing that such existences originally incubated (a thing that in this story is also seen to be unwelcome and invasive depending on context or consent), a thing that the woman here also brings into being by desperately (mindlessly?) unravelling a man’s belt (compare and contrast the almost autonomous phallus in the first story). Just inferring. A great story, even without such inferences. Cycles of passion, as well as cycles of finance, set against the eternity of myth. Boom and big bang. (25 Apr 12 – 2.35 pm bst)

“Something was missing from this nether, neither world.”

A sort of Ghostwatch TV programme turns gory with this book’s sometime bodily sense of flensed calligraphy or surgical graffiti, and Martha, tutored originally by those already passed, now possessed by them, her mother Iris and sister Suki, and somehow, while lacking their medium skills, exceeds them, as the camera and TV politics of showmanship explore a cellar bar that was once a cruel prison. A tale with the heft of touching distances, I guess. Neither here nor there, but both as real as each other. With blade-nicked names named.

“I wanted you to see the water. It’s just like your eyes.”

A modern urban story with elements of Greek mythology and with a miscegenative affair that makes this 2012 story the perfect accompaniment for the recent film ‘The Shape of Water’. Pearls of Priya. With the fabulousness of beasts.

===========================

The Absent Shade by Priya Sharma

“…no idea just how important, how long a shadow those days would cast.”

You will need to read this original and charming Charwoman’s Shadow tale of tea and Proustian cakes, in order to see quite how clever the words in that quote from it actually are. This is a sinuous, sometimes sexual text interweaving a boy and the boy as man, within the striking ambiance of Hong Kong, with jealousies of women as mistresses and servants, as well the boy’s with mother and father and the one who taught him to cast independent silhouette shapes upon the walls of time. A telling tug upon the fast-vanishing tail of one’s otherwise slowly fleeting life, or a tug upon that of others. As in the previous story, we believe there is always something to hang on to.

“I’m going to hell when I die and it’ll be Sandbach Motorway Services. What was once a beacon of convenience for modern travellers is now a carbuncle.”

When I first read that bit, I misread ‘beacon’ as ‘bacon’! Also, as perhaps intended by the author, I wrongly assigned the Peter (referred to by Cheryl the narrator as ‘you’) to quite a different and real Peter… in fact, it is a dysfunctional story, in an effective way, about Cheryl’s dysfunctional life and family, from the 1970s up to the present, but mainly the 1980s, not in a linear way, but dotted about, but the trend and the ultimate outcome become clear – and clearly devastating, at that. A story of a place around Sandbach, its people, a place also as a symbol of many of our lives amid social change and inborn intellectuality deprived. And sudden crimes of passion. And moments of young passion, too, in fitful starts. From analogue records with hiss to digital, under a Cloud. (Bosley).

This book migrates its dreamcatch or haul from earlier flaying and flensing towards, here, an act of filleting fish. It is the sea-steeped story of another Peter, with whom a fishing life’s random chances of good and ill smashed his leg but brought to him — on tantamount to the next tide and to his small fishing community — the beauteous slow-drawn nakedness of Marianne. She chose Peter. And I see this story as another of barrenness sorrow, earlier in this book caused by endometriosis, here perhaps a sorrow assuaged by the eventual mutual donning masquerade of the mer-ry and the fishtailed. There is always, I guess, another means of dressing for partnered sex, keeping it fresh, despite that sorrow. Also a constructive synergy with some stories by Caitlín R Kiernan I reviewed recently. That slippery gestalt with vestigial gills like ears. The fabulousness of beasts. And a further shape of water.

“Don’t close your mind to the idea that beneath what we know there’s a whole world that we can only guess at. There are things in life that we know that we don’t understand. The real danger is the stuff in the blind spot that we don’t know even exists.”

Another flotsam birth like Marianne, here a belated ‘secondary drowning’ by the lungs’ own tenure of a near-drowning’s diminution, as we follow Cariad in her career in Accident and Emergency, the acceptability of wounds that otherwise horrified us in this book’s earlier flensing and flaying, but here the damage is more mental amid the onward rush and diminished resources of such Casualty situations that can so easily allow through the odd lethal mistakes, and then in her Welsh home, one such self-blame comes back to haunt her, along with the terrifying sea itself. Being half-Welsh myself, the story’s scenic ambiance is re-invoked by an easily missed observation of story’s symptom towards its end: the sometimes seemingly random letters of the language my forebears once spoke, now an algebra of meanings that “rearranged themselves.” My Arosfa soon enough to become my Cartref. Cariad’s, too.

A striking portrait, through his own eyes and the saliva sea in his mouth, of this ageing Englishman, not an Englishman with inverted commas but a genuine Englishman, from England, a man of the Indian race, widowered by a once miscegenate-considered marriage with an English rose of a wife and her family and her religion of quiet country churches. He once promised to show her India, but now too late, because she is dead, and in hindsight, this outcome is probably best. He has himself returned, however, but feeling paradoxically nostalgic for the hierarchical mœurs of India sixty years ago, absorbed now with the smells and colours and poverty and subsidal constructions, and India’s godly pantheism that parallels his own willing subsidence or subsuming within a new pantheism of self, as India claws him back, not as the shape of water, but the shape of India. Not an oxymoron so much, as a new spiritual oxygen to help him breathe when experiencing whatever fabulous realm resides within the veneer of detritus. Or its Marabar Caves.

“, the Om that underlies the universe.”

A simple story of honey-rapture and bees and a woman in the ripe summer of her body and her chance taking of the beekeeper’s cottage and the ‘rotten door’ leading to the orchard and the man and his ‘family’ that take her up as intrinsic to the objective-correlative of the hierarchies of a hive, with ironic reference to this book’s treatment of barrenness, now assuaged by the arrival of her singular royal ripeness. Coveny as well as hivey.

“He wasn’t to know the ways in which I’m made for water.”

A narrator, a dreamer of the sea and what is in it, can hold his breath for half an hour under it, a young footloose man, working in island bars, seahorses ground up for erectile dysfunction germane to his thoughts, and he is called back to a genius-loci Hong Kong where his ‘father’, if a foundling can have a father, has, on sudden death, left him their flat there and a fortune or so it is supposed. But there are other machinations, a destiny beyond these surface facts, germane to this book’s parenthood or lack of it, its now definite Shape of Water, with ‘giant wetroom’ trappings, as well as human-fish trappings, then through the previous story’s ‘rotten door’, here rotten houses on stilts, to hear “humming”, and not towards a Queen Bee but as a King of the sea to spread his now unendo seed. Having first been fed sharkfin soup, I infer. Some magnificent descriptions here, and emotions reaching beyond spirituality and sex and sea. A major work, still soughing around me.

“There it was. The great mystery. We were synchronised. Our rhythm was primal. Tidal.”

“So it is that serpents are reviled when it’s man that is repulsive.”

Strange that repulsive echoes with reptiles. Reviled, too. And Bill Shankly was shamefully never made into a Sir…

This story grows increasingly shocking as its East Enders type soap opera — of a dysfunctional family in Liverpool, with diamond rogues, their women as princesses, between prison visits — accretes in our mind, and the incestuous and weresnake implications. A chronologically non-linear patchwork backstory of itself, with slithery transformations.

end