Des Lewis’ ‘real-time’ reviews are unique, thought-provoking and always a treat to read. They’re packed with word play and poetry as they unearth associations and currents in the work that I might miss myself when I’ve been so close to it. Other writers describe similar experiences of discovery and regard a Des Lewis review as a work of literature in its own right. I second that. Perhaps you can call this a review of a review. I always feel very honoured by the attention and thought Des puts into his reviews.

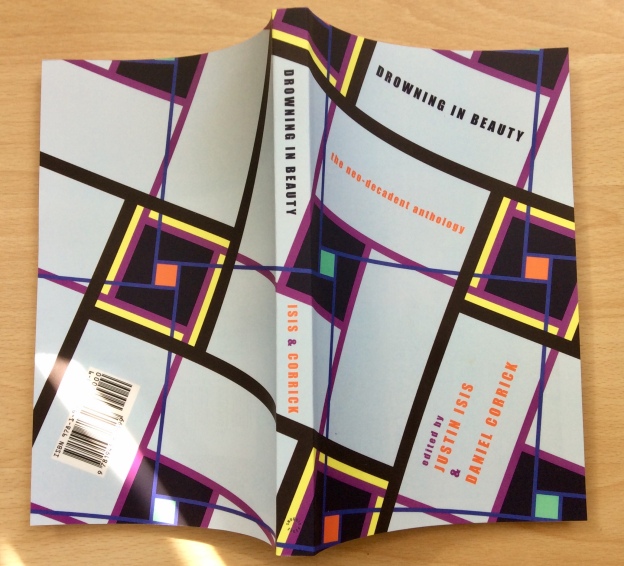

They are usually beautifully illustrated as well. I’ve included his cut-out of the tiles from “Lambeth North” that appears on the cover of R&R below, which he connects with the avatar he uses on website. After his exploration of each story, Des sums up:

“Resonance & Revolt. From Didcott to Didactic, a grail or Rosannation for socialist outreach but made even more palatable as percolated by truth and inspirationally infused by the book’s creative tapping of histories, myths and alternate visions, transfigured from rustblind through to silverbright. Some very important stories in this book transcending any didacticism. And a gestalt of them all that will be enduring. And a book cover that sings out with all these things.”

“Resonance & Revolt. From Didcott to Didactic, a grail or Rosannation for socialist outreach but made even more palatable as percolated by truth and inspirationally infused by the book’s creative tapping of histories, myths and alternate visions, transfigured from rustblind through to silverbright. Some very important stories in this book transcending any didacticism. And a gestalt of them all that will be enduring. And a book cover that sings out with all these things.”

“, the bird emerges, one puzzle piece after another.”

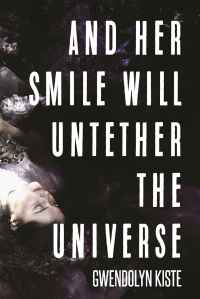

A fluke that I read this today only a couple of hours after the Royal Wedding. Not only because of the place name of that Wedding – Windsor – but also I can imagine the bride being taken across the threshold like a newly wed, borne like a bird-bride, with great hope, for a fluke’s flight, but the sharp-eyed bride in Windsor, will she, too, give spiky bird-birth and relegate her husband elsewhere? And then fly with the fluke of the birds that re-impregnate themselves within her. Tried to catch this story in my dreamcatcher net. But it keeps flying out again. Each puzzle piece bird reaching endlessly through each unconfinement upon the sore winds for their gestalt? To untether their universe?

“I dream of marking the right answers. But not Tally. She’ll never color the correct circles. She’ll score a fifty—the worst number—and she’ll laugh and I’ll laugh too. Because if anything’s contagious in that town, it’s her.”

This starts with a comforter as a bed tether, to prevent vanishment. Vivienne and her co-special friend Tally grow past 16 in this story, a story disguised as a freehold, if feelfree, set of Vivienne’s written responses to ten test questions that are supposed to reveal grades of vulnerability to vanishment or untetherment, as those of us in our world or universe seem to be vanishing, possibly in response to the gestalt of things growing worse in that same world. We, as readers, are meant to join in, thus tallying, as it were, our own scores of vulnerability or susceptibility as we go through the questions. But some of us will, by its own logic, never finish reading this story. Vanishing before the end.

Contagious ‘hoisting’ or hawling.

“Now we know for certain where I’m going.”

A sororal message left in a vintage bathroom vessel, beyond any Mason and Dixon line of the soul? The border dispute of death. Whether natural or induced. Induced by self or a busybody aunt or both. This is a very disturbing, poetic, eventually inspiring tale that adumbrates such things. But I have tried not to open the casket of this story.

“But if I arranged for a closed casket, they’d invent scenarios far grislier than the truth.”

So, yes, I will need to open it at least partly. I am not that unknown man who visited the ‘wake’, amid the surviving guilt of the sister left behind as she nurtured the vesseled-blood component of the sister’s gestalt, a component itself left behind outside the casket by dint of the retentive clawback in the bathroom where the stoical death had taken place. Nor am I Joseph, whom the surviving sister built into a gestalt of recognition from his many strange, unrecognisable parts. Parts of her own sin? I am certainly not the aunt who thought the first man to be the dead sister’s sin. The aunt who said: “She was a ghost even when she was alive.” All aunts once had to be a sister to be an aunt at all. Not one of those visiting flies that came to settle upon the blood that linked one to another.

A powerful story and the mannered cynicism of mourning at last transcended.

A Corinthian Clawfoot Bath

“They’re busy cooing over satin and white stallions, and tethering rusted tin to the tail-board of the royal carriage.

The young ladies cry because it’s all so romantic.”

“She married a prince. What more could a poor village girl desire?”

From the point of view of an, initially, 5 year old girl, this is a memorable dark fairy story, during her growing-up years, where she sees that one bite of an apple by the other girls is tantamount to their being kissed by each Prince or other male dignitary who arrives, not kissed as Sleeping Beauties but as poisoned brides-to-be and then taken in marriage. All constrained by a difficult relationship with her father who thus earns match-making money from owning the orchard where these apples grow, and we are subsumed as readers by a recurrent witnessing of this curse and the way everything is described, a universal curse eventually relieved or untethered for us by our imagining this universe not being kissed by a Prince but being Kiste by this story.

Meghan Markle the apple of her father’s eye

“Mice,” I told him. “It’s only mice.”

Dear Story (if that is what you are),

Mice in the wall, and a man, if not exactly mice and men?

At first, the sixteen year old girl writes letters to what we assume to be an imaginary friend in the ‘ambry’ or cabinet in her bedroom. A man she eventually calls Andrew, by imagined responses as to his name. But she grows up still writing to him, leaving the reader privy to these letters. But I wonder if he is the real one, and she the imaginary friend, a sort of pyramidal Eucharist or Pyx, that the ambry and her are sharing as a single synergy. But of course all imaginary friends in fiction (or even faith) are unreliable narrators, I guess.

Yours, your reader.

“She mourned too long,” my husband says. “She mourned until something came back.”

A brief, simple, haunting and touching story of a mother’s wishful thinking of playing hide and seek with her daughter and thus bringing her back out of death’s hiding. Perhaps still as small as her shadow? But not simple at all, when seen in this book’s context or gestalt?

“Yours, Now & Forever,”

And ‘Forever’ must continue beyond the end of Kaylee’s story, the progress of her pregnancy still a healthy one. In fact, with this story, the previous AMBRY becomes Kaylee’s AUDREY, a retributive ghost in the shape of Audrey, Audrey who did away with herself when Kaylee married Audrey’s boy friend and now Kaylee is pregnant with his child. Audrey’s ghost leaves grooves in the carpet when its body slithers towards Kaylee at night, sometimes even when tethered by daylight. Another story that is deceptively simple with short paragraphs, but one that is so powerful by transcending, one senses, some complexity, a complexity hidden in plain sight. Embryo developed and primed in the Ambry.

“, tales that usually made her smile.”

Two young sisters, in hopeful make-believe synergy, often sleeping in proximity, in never let me go bouts of girly small talk. But a dark irony overhangs this whole haunting, sometimes precarious smileability, the men in peacoats at the camp officiating, the trial and error, red days, red light surveillance, connivance by their parents, a wilted ponytail, visits to the moon or Mars, videos of inculcation… yet, I shrugged off such irony and joined with their smileability, still trying to untether, uncouple the fragmentary make-believe power of hope from emoticon reality – and make such potential power whole, all that there is. A pea green boat not a peacoat.

“This tourist town dies a little each day, and with our bodies always wilting, so do we.”

I live in such a place, with a pier, and a sea that’s made of several skins. And a wife who quilts many quilts. Including the quilt that is my avatar. Like Honey and Sea. Meanwhile, this story is an astonishing, unmissable tour de force. It has the premise of our bodies shedding many skins over the years, but here they stick together and can be mutually rifled, intra-gender, too, with much of today’s mores of such sexual or emotional or spiritual or bodily exchanges, amid a scenario of Sapphic loves and jealousies, amid flays and flensings, in a genius loci simply to die for. I was highly moved. And reskinned, if not rejuvenated. Untethering.

“You’ll think it’s safe. You’ll bring her into this place where you and I danced together, where we pretended to believe in forever.”

That ‘forever’ again – probably.

Here, a museum’s stasis-in-aspic as emblem of a eureka moment crystallised by this exorcisable narrator knowing she will never be exorcised, knowing this by dint of some Zeno’s Paradox of spirit, here speaking with her widower about a forever forever, not any shortened forever she was promised before this real one started. Now, a promised ‘love triangle’ of unexorcisables whereby any ‘probably’ is impossible in the avenging hindsight she has created.

A hate triangle, for ever and ever, amen.

“But here inside these walls, where lonely children live, you aren’t supposed to care about spells or magnetic sand or dream-catchers in windows. Magic can’t be yours. That’s what the unsmiling women tell you.”

Two sisters, one marries. Now the unmarried sister has magic without the synergy of magic with the other. Her sister’s husband to be magicked and tallied for what he does, for what he did. Part of the avengement embodied in the previous story. Another man, her sister’s grandson, to be dreamcaught by this work, I guess, by a pantheistic witchery that my own dreamcatcher still tussles with and perhaps tussles with, forever till forever ends, if forever can out-tally its own Zeno’s Paradox. Some of you will cherish such hopes and battles and honourings, and read yourselves into a good synergy with it, taking your just deserts and the rough with the smooth. A rhapsody of love or “just another tally mark.” Probably, both.

======================

THE TOWER PRINCESSES

“I tell myself the wind swallows the paper, or a mama bird stuffs my handwriting in her nest as fodder.”

Tower princesses reminding me at first of the earlier Rapunzel-like Princess called Ellie – but soon becoming, here, a deadpan taking-for-granted that there are some girls in Mary the narrator’s school, girls who are within towers like burqas, I thought, but not really burqas at all, but the very thought about burqas does resonate with the earlier Allah version of mendicants in the Larson…. No, these are like vertical shells, of different materials, and Mary strikes up a relationship with one of them, via the slits of the girl’s tower. The story also deals with bullying as well as incestuous rape upon Mary. This work I treat on its own. Startlingly provocative, enough.

“She’s a mosaic, and I have to cobble together the pieces”

But the Kiste also conveys the rite of passage of a young girl as the Devlin does, each tower princess left alone at home like Cinderella but inside her own bespoke mobile home, having become the princess through fitting this body shell (cf the body gloves in the Larson) as Cinderella’s foot fitted a slipper. But once out, what do they become. Born from themselves as mother shed to become child, so as to migrate…and then the shed tower to be used by others for incubation like within Ellie’s earlier chrysalis husk – or like the cyborg trigger within Larson’s Marina. Build up your own brainstorming in the comments below if you have been excited, like me, by this clutch of stories, each awaiting its own further migration.

“You don’t want to see what they do to her, those monsters hiding in plain sight.”

And the ‘And’ in the title is all important. That forever AND. Here, I can imagine a reader of this story — reading about its “urban legend” of an otherwise obscure actress in a handful of hard to get films and of the ‘you’ with which the reader is addressed by this haunting description of such a phenomenon — who might also see its author smiling at him or her through the ‘fourth wall’ of the text. Probably.

The chance is to try synchronise them like a secret palimpsest. A needle judiciously placed in each groove. As the story itself infers. A story to become vintage Kiste, I predict. Not obscure at all.

“I was there for the art. That was what I told myself. But I was really there for you.”

We ever recur to the beginning. And I started reading this book on the day of the Royal Wedding. And here we return to a morphed version of it, as if the bride of this story painted it. Gaunt tower-princesses and pillars of salt.

But still a “fairy tale wedding.” ‘Transforming the beast back into royalty.’ ‘Coaxing the apple-poisoned princess from her grave.‘ ‘The comforter kicked back.’

And the love remains … forever? Probably, I say, despite the recurring bridal pyre. The ash remembers. Healed here in a “claw-foot tub.”

The TED Klein General Store of real life characters and observations, to boot.

I am not one of this story’s “pawing guests”, but still a reader (un)tethered by the containing book’s wonderfully cathartic gestalt. Its emotional and spiritual universe.

“You outfoxed me by a mile, and you grinned over the rim of your cocktail glass, because you knew it.”

end