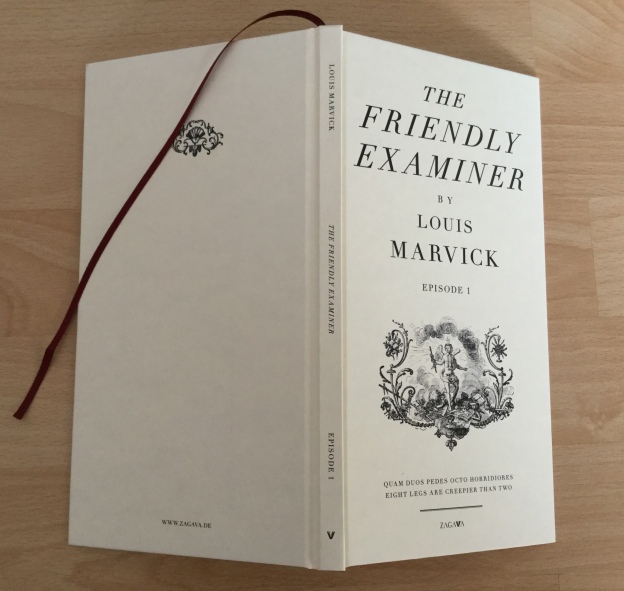

The Friendly Examiner, Episode 1 – Louis Marvick

ZAGAVA MMXVIII

When I review this publication, my thoughts will appear in the comment stream below…

www.nemonymous.com

Des Lewis - GESTALT REAL-TIME BOOK REVIEWS

A FEARLESS FAITH IN FICTION — THE PASSION OF THE READING MOMENT CRYSTALLISED — Empirical literary critiques from 2008 as based on purchased books.

Read up to: “He is only twenty-three, but he feels sixty-two.”

Read up to: “He is only twenty-three, but he feels sixty-two.”

Bernard’s wife’s relationship with him, as well as the duties of the Bistro job, conjugate a gradual descent into Binnish catchphrasitis consumingly conveyed by Campbell … and later a Binn live performance in the local area that Bernard attends as a disciple and doppelgänger whom Binn recognises from the stage. The ‘dying-fall’ repercussions make me wonder if most writers have their own doppelgängers, just slightly off-kilter, and, if so, perhaps better, perhaps worse, their fountain pen as well as their smartphone-camera reversing or swivelling between? “Can we start again?”

Bernard’s wife’s relationship with him, as well as the duties of the Bistro job, conjugate a gradual descent into Binnish catchphrasitis consumingly conveyed by Campbell … and later a Binn live performance in the local area that Bernard attends as a disciple and doppelgänger whom Binn recognises from the stage. The ‘dying-fall’ repercussions make me wonder if most writers have their own doppelgängers, just slightly off-kilter, and, if so, perhaps better, perhaps worse, their fountain pen as well as their smartphone-camera reversing or swivelling between? “Can we start again?”

My previous reviews of ZAGAVA: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/zagava/

“The assassination of Donald Trump.”

A very moving account of the narrator’s dead brother and painterly words channelled between them, their barely surviving mother of 90 now vicariously channelling for her sons the vistas of the Glasgow flightpaths above their home, and this first piece of prose itself channelling towards the book’s next story that they all will now tell us, via the dead one, I guess. We shall see.

“In surprising but enlightening connections, forged across your memory and conscience, across time and space.”

A smoothly stylish and, for me, inspiring portrait of the shop — told by the resurrected dead brother in their mother’s attic to the surviving brother (guilt-ridden by that brother’s death) who in turn re-tells us here as part of this book — the eponymous shop which is a miraculous hardware shop run by a sterling Sikh, magically providing all your needs crucial, trivial and crazy, but only if you are the right sort of customer, a shop as a sort of Tardis with things blooming like books, a wisdom, a sense of battling with and against politics such as good and bad referenda, historic partitions, even the scourge of Nigel Farage, a Far Age of Righteous Dysfunction, I guess, all of these factors often out of keeping with your beloved homes and homelands that are intrinsic to your strength of inner and outer imagination as sown with cosmopolitan riches.

“, a wallflower sapped by congenital anaemia, compared to its swelling trunks and swooping vines, the constant symphonies of birdsong…”

A heady mix of connections with Escher stairways between them, connections such as a French sentence repeated from the previous story, and the shop’s Tardis like qualities transposed here, and this book’s ‘dead brother’ addressed again, and the earlier attic with its stories passing down to us, is now represented by the sieve-like irrigation from the top of this story’s House’s top storey, a house in France as a Huysmans, an arguably anthropomorphised house man with decadent or pessimistic philosophers as part of its structure. It starts as the narrator unexpectedly inherits this large rambling house in France and, with increasingly manic intent, as supplemented by another inheritance of money, he rebuilds it almost with defiant counterintuitive Green purpose towards a new Hanging Gardens. I found it a breathless journey unexpectedly revealed here. With an idiot dunce called Desmond to aid and abet the narrator.

Towards Nature by Douglas Thompson

“I was encouraged by the lawyer to maintain the services of my uncle’s erstwhile housekeeper Madame Le Lancourt and her slow-witted son Desmond,”

At the time I last read and reviewed a story by this author here, I wrote: “Whenever I read a Douglas Thompson story, I feel as if I am looking through a fiction-microscope where physically beautiful words of all lengths and mineral or jellyfish or orchid qualities shimmer or prick one into a special magic reality, then miraculously turning such microscopic visions into a vast macroscopic imaginarium that one can ‘bank’ as if within some accreting noumenon-sump that is somewhere inside yourself even if you do not always consciously remember the process.”

— and this story does not disappoint in this light, if anything I ever write can be deemed to be ‘light’!

This story of the first person protagonist’s inheritance of an effectively ‘listed’, ‘preservation-ordered’ Villa Duendelle and his constructive desecration of it by Nature into a wondrous Hanging Garden is a perfect gem of Decadent Literature, rest assured. It does also serve to “cross-pollinate” with Wood’s earlier pollen-in-the-pocket and the London Bridge crossing civil servant or financier (like I was once myself): “He was an odious little jobsworth in a black suit and pince-nez, exactly the kind of world-hating nature-hating petty bureaucrat that we picture the writer JK Huysmans masquerading as for most of his life in the civil service, without, of course, the redeeming imagination.”

“…from where the mind of every living soul far above us can be glimpsed like stars in the night sky […] What do I fear most? To meet God. The light of god, falling towards me, probing out the contorted bowels of the earth, […] peering past the ruby red lips and the rotten teeth, of young and old.”

My previous review of the next story is shown below from when it first appeared in WOUND OF WOUNDS (Ex Occidente Press), an anthology inspired by Emil Cioran and this story features a character called Emil.

It seems highly significant that I re-encounter this story on the same day as I read and reviewed (about half an hour ago!) this co-resonant, but fundamentally different, work, THE CIRCLES OF GODS by Holly Heisey here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2018/11/11/humanagerie/#comment-14236

===================================

In ‘Wound of Wounds’:

BACH’S MARIONETTES

“The light of god, falling towards me, probing out the contorted bowels of the earth in search or me, his huge eye burning above me like an accursed sun,…”

A Parisian genius loci to die for.

The above quote and a flea market above the bowels of the earth and the beats from under the pavement, a mention of Proust, and this makes me feel at home in some Nemonymous night of my own… but, beyond this, I think I can safely say the Douglas Thompson story is a literary classic that you will remember, where Emil meets God in His deux or deus chevaux car, God who is also Bach, in charge, He claims, of all we marionettes of humanity. It is wondrously acceptable as some intrinsic poetic truth that only inspired works can own. I also happened to be listening, coincidentally, to Bach (Orchestral Suite No. 2, the famous flute solo in which is significant to my earlier life), listening to it from before I picked up this book today and started reading this its next story.

====================================

I shall now read TORLOISK, ISLE OF MULL that seems to represent a new set of passages added to the end of ‘Bach’s Marionettes.’

Except I don’t imagine them! They emerge autonomously, whether transgressing Wimsatt’s Intentional Fallacy or not! I reveal their emergence.

“And the dark beast is abroad again. Roaming this endless dark of self-doubt which surrounds me…”

This TORLOISK section is a moving one about personal relationship matters, beautifully described, also with further references to his dead brother dreaming him, attic dreams, and again the guilt involved with once destroying that brother’s flying saucer. Ending with an intro to the next story that is about Trump…

“, his perpetually grimacing face, as if chewing on a wasp, or like a well-skelped erse, as we say in Glasgow, his red baseball hat, his uncannily dainty little hands.”

This may be the most frightening and poignant few pages you are ever likely to read, involving the eponymous nightmare arrival on the world stage (you will never know Trump to his bottom core till you read this description of him: a necessity to do this for potential catharsis, even if you don’t want to do so) and involving personal Scottish matters, such as the narrator’s mother and the death of his brother. And God’s giant eyeball, to boot, the last ace card as an attempted trumping of Trump himself?

THE SEA

“What are carpets for if not brushing things under?”

“For a Machine it would be no problem. They don’t need the patterns and meanings that we find to delude ourselves, to console and terrify ourselves.”

But a Machine can live, I guess. Absorbing all these stories, processing them, hawling them by feeding back into them. Despite its deceptive size, this is not a novella; it’s just the next staging post as we read alongside the narrator, about another narrator, the written narration of a woman next to his mother in hospital, a woman, as she tells of her job clearing houses in Glasgow, then living in the house she has almost cleared, except for the eponymous hardcore machine, a thing with vents and apertures, not a storage heater or utility convector, but something that almost acts erotically or uterinely, like those people once trusted around her eventually do so, too, a surrogate father (indirectly echoing her real father’s previous abuse upon her), and a woman friend, auto-erotic or two-way sex, somehow mingled with politics like Brexit and the Scottish Referendum. And Russian spooks. And a Russian backstory of a quantum scientist into the paranormal. Who or what is in that machine, what dire effects it has, it will haunt me with this book’s intermittent Tardis quality and hardcore prehensility. Blending in with dreams that could have come from Twin Peaks, Series Three. A conveyor belt that has linear and non-linear qualities of memories and time travel … towards the next stage in this book’s auto-biography, as I shall call it, now complete with the telling hyphen. A machine that is a trope for a dead brother? This is a work where even info-dumps become part of my reviewing machine’s own feedback… make of that what you will.

“What is that President Chump up to? And what on earth is Brexit?”

Very moving and touches me to the core as I read this transcript. As he promised earlier, the narrator interviews his mother, in her ageing version of life’s Tardis, I guess, just as I myself once interviewed on cassette tape my grandmother about her experience of the two World Wars, her difficult marriage, birth of my mother and uncle, and later I interviewed my mother about the Second World War, meeting my Welsh father, then having me…

Of course, I was and still am only an only child. No Ally for me. No failing stare. No falling stair.

“Have you ever paused for a second to consider the idea that everything in the universe is about holes and interpenetration? — Not just the human reproductive system.”

This is the epilogue to the earlier novella-length work and it is also the coda to this whole book’s symphony, its auto-gestalt of fraternal frames in painterly parental palimpsest. As that epilogue, we see things through the pervading mind of this book’s friendly examiner (Voltaire’s best of all worlds dictum), extrapolated as a Russian ‘mad scientist’, who is not mad at all if we can apply our own creative madness to his bodily array of wormhole sores as bouts of time travel making things ‘slightly better’ than worse in any one of our worlds… except we’ve ended up here today with Chump and the fastest ever neologism becoming a real word? As the above mentioned coda, we realise that the Machine Stops with EM Forster or the Hadron Collider and the Internet, and that ‘slightly better’ means a fraternal faint rather than any lethal jump into a Fallen West. A feint or counter-feint. This book is auto-personally monumental and momentous – miraculously meted out, too, for its readers. Somehow a shared journey in more ways than one. The riddle, for me, is in the sands.

end