The ship’s captain had “a black uniform set out with rusty gold lace”, but surely gold doesn’t rust? — from my recent review of ‘The Ghost Ship’ by Richard Middleton, a story chosen by Aickman for the Fontana Great Ghosts series.

THE BREAKTHROUGH by Robert Aickman

“‘I’m not sure that gold does rust, Slow,’…”

This story’s gold does also rust, as slowly as what I have recently discovered to be Aickman’s instinctive absorption by Zeno’s Paradox in his writing of fiction and editing of Fontana, a story’s rusting, that is, from the gold of the first three-quarters towards its final quarter?

My contention is that the first three-quarters approximately of this story represents the finest horror or strange or weird or ghost story in literature; and it would now be lauded as such high and low, but only if Aickman had rounded it off before reaching the more ludicrous aspects in the last quarter, aspects of purging or catharsis, leadership-and-individuals, the ‘crowd power’ of pitchfork locals who are out for hangings or murder, and the narrator’s clumsy dealing with a particular woman or philosophising about women in general…

Meanwhile, therefore, I deal below with the earlier main body of this work, one that is intrinsically disturbing and revelatory: the Aickman masterpiece, in fact. We slowly become aware of the narrator, Mr Walmen van Goort, “a man difficult to surprise either by angel or by devil”, being the village’s educated man, a man of the world, who had travelled in many cities, like loving the ladies of Madrid and having what he describes as his “years of illusion”, and much more — and we also meet the nose-prominent, shrimp-like Reverend Mr Stooling, and the dogged ‘Old Slow’, both classic characters. We also learn of the vital reconstruction of the church and the huge heavy lead globe that the workmen accidentally drop to the church floor, smashing the floor and releasing what fell force by such a fell breakthrough? …

I then sense a clinching redefinition or prophecy, here, of what exactly the nature of today’s co-vivid dream is, and it firstly resides between these two items of dialogue:

“‘Then, you are telling me that all these different fully grown people are having the same nightmare, and a child’s nightmare at that?’

‘No. In this case it is a nightmare for none. It is a reality for all. A reality that is new to most. It is the nightmare come to life.’”

And then this dialogue is interrupted by the narrator seeing a big bee “reclining in the deep dust of the table.”

The co-vivid dream then is said to be “Also about forms of whom people see only the backs and never the faces. Also about rooms turned inside out or upside down: rooms moving from the ground floor to the floor upstairs, or substituting what had been a window for what had been a door.”

All of us can visualise what we see in this story, our own bespoke ghosts, beasts and other horrors — as the characters in the story also do. And we are made to see theirs, too. Horrifically or spiritually nightmarish at the highest point of this master’s conception.

Recognising Hell, while realising you are still in it.

“The truth was so greatly worse that he had suggested, and so greatly different from it, and so greatly greater in all ways.”

Whether the distance of time or the division into quarters are exact, I still wonder. From gold to rust.

“‘I’m not sure that time is the essence, Slow,’….”

***

PS: a quotation from what I consider to be the apocrypha of this story’s final variable quarter:

“‘No, sir,’ said Lewis. ‘It’s not that. We all know that’s in good hands.’”

All my reviews of Aickman: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/robert-aickman/

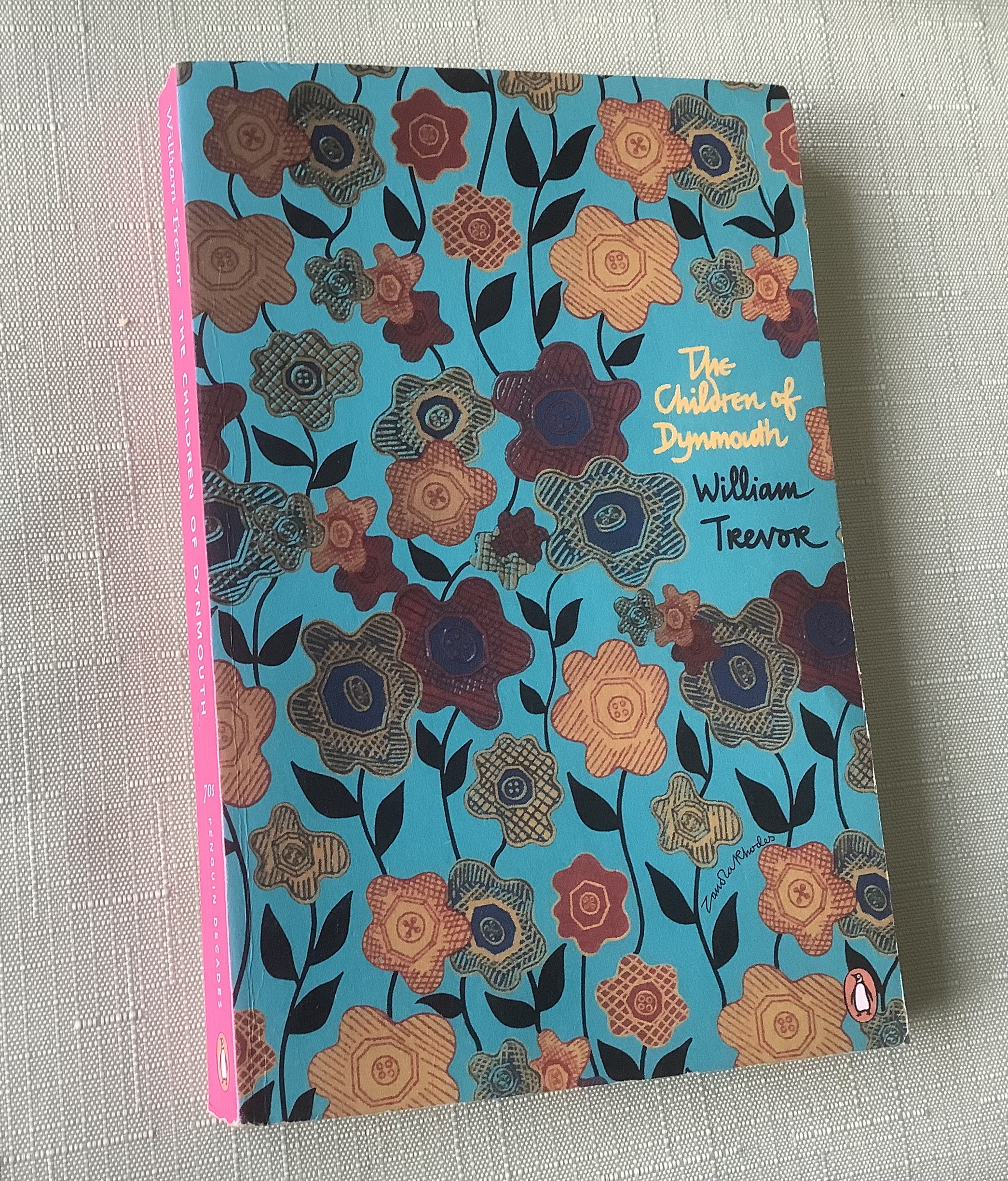

Chapter 1

Pages 1 – 11

“The children of Dynmouth were as children anywhere. They led double lives; more regularly than their elders they travelled without moving from a room.”

Or moving from a town like Dynmouth? And we receive an engaging portrait of this Dorset seaside town, a town that to many would be unengaging to live in for any length of time! A town with a pier and a hill called Once Hill ….and a sandpaper factory! We meet the Featherstones of the Rectory, with twin 4 year old daughters who seem to believe that jam can fall. To be their only children following a miscarriage.

And we meet other characters whom I shall not list here, including, for at least the time being, the one whom I anticipate being this book’s central character, one who calls the vicar ‘Mr Feather’ without the ‘stone’.

Pages 11 – 27

These pages are honestly stranger or better than even some of the best or strangest of Aickman. I can’t itemise all the ingredients here, but it seemed the essence of some 1960/70s era when people seemed to act or behave like this, and watched Benny Hill or Hughie Greene or Crossroads. And when everyone was most peculiar. Today hasn’t got a patch on those days. We can no longer act or behave at all, but simply oscillate between the ends of a spectrum of awarenesses and various incorrectnesses that we hate or think we hate.

I will never do justice to this book, so perhaps I won’t try!

See how I go, while I read on to the end of this book, as I definitely will — whether or not I report any further on it here.

Chapter 2

“…she had been caught at midnight by Miss Rist performing rituals culled from a television documentary about the tribes of the Amazon.”

…Kate, that is, in the school dorm, one of two 12 year olds, the other being Stephen in a separate school, now joined as brother and sister by dint of his widowed father marrying her divorced mother; we learn of the earlier sad circumstances of Stephen’s loss of his mother, and that Kate hopes one day she and Stephen will will marry….

Travelling to Dynmouth on a train to be looked after there until their parents come back from honeymoon.

We also learn about Stephen’s boarding shoot, and that one of his teachers nickname Dirty. Because he once confessed never to have washed his hair, we are led to believe!

I have an ominous sense, knowing what I already know from the previous chapter.

This is trepidatiously wonderful, entering the world of William Trevor again after my real-time reviewing in detail all of his many stories a year or two ago…

Chapter 3

“It was sticking to your guns that had made England, once, what England once had been. Nowadays it was like living in a rubbish dump.”

This chapter is a veritable tour-de-force. I have never quite read anything like it before — accessible, simple, complicated, too, very disturbing, being a series of streams of consciousness of those inhabitants, young and old who dyncopate Dynmouth, and it is something in synergy with Ramsey Campbell from his Grin of the Dark mood. And much more, with us actually experiencing the thoughts of an awkward adolescent boy getting gradually drunk having been offered a series of alcoholic drinks by an adult who should have known better, and other acts of clumsy dressing up or charades, oven cleaning, plus much talk of others’ indecencies, and there are autonomous believable incursions from Hughie Greene, Benny Hill and Bruce Forsyth! And it all makes sense. Nonsense, too. And this opportunity knocks for any new reader of William Trevor to read a book that may have been overlooked….and especially for those who already know my real-time reviewing, this opportunity cannot be readily sneezed it.

Pingback: Grins in the Dark | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time Reviews Edit

Chapters 4 & 5

“The best place for Dynmouth people is in their coffins.”

This compelling novel that one resists to find quite so compelling miraculously conveys believable plot elements bordering on grotesque or comic behaviour, while summoning aspects of truly felt sadness involving a lifetime’s disappointment suddenly poking its head into your twilight — and of shame as well as shamelessness, in various characters. Including the blackmail invoked by our awkward adolescent to gain stage curtains, a wedding dress as costume and a tin bath for his proposed ‘Spot the Talent’ ambitions when that event takes places at the forthcoming fête, and his insidious befriending of Stephen and Kate at a special cinema performance of Dr. No… There are aspects here that I do not enjoy countenancing, but still I turn the book’s pages, on and on. The delayed delivery of now lukewarm or congealed Meals on Wheels, followed by two boiled eggs in eggcups talking to each other, notwithstanding … or did I get that last bit wrong?

Chapters 6 and 7

“The most marvellous smile they’d ever seen, the biggest in the world.”

This is just as disturbing as I feared. Or hoped.

I shall now make this a voiceless review, except perhaps for chuckles off-stage, upon the raising of the Hughie Greene eyebrow. And, yes, insidious shifting sounds of an adolescent thick-skinned poltergeist. A rustling wedding dress and a cliff side, sea side scream.

“After all this ugliness, like a slime around them,…”

To be continued in due course…

https://vaultofevil.proboards.com/post/70482/thread

Pingback: Like a smile around them | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time ReviewsEdit

Chapters 8 – 12

Amid God’s ‘shades of grey’ and His machinations of ‘chance’, we are led to explore many things we fail to understand, while actually fully understanding them in a steady-state conduit of ourselves of which we are rarely conscious. Much here, meanwhile, leaves a bad taste in the mouth, but much of this is cured by stoicism and facing the secrets in all our lives, even secrets we keep from our own conscious mind, secrets kept in that hidden conduit of the self where we direct emotional overflow, where any blockages would otherwise fester. This potentially dangerous book cannot be placed there, as the state of being in-denial is what it tries to destroy. Helps clear the blockages, counterintuitively? Including always liking Petula Clark’s ‘Downtown.’ A mischievously comic book by a god of tragic literature. While siphoning cheap entertainment of an era, it is also a book that helps dredge dread.

“…his smile still giving her the creeps.”

But whose smile? The author’s?