Bastards of the Absolute – Adam S. Cantwell

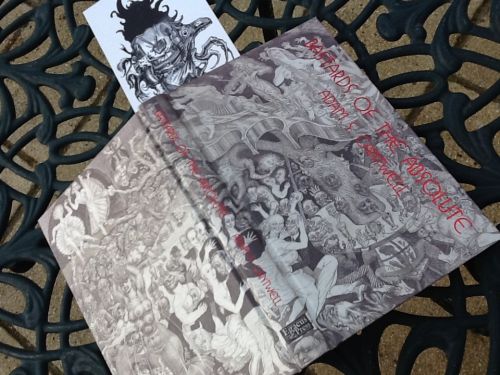

BASTARDS OF THE ABSOLUTE by Adam S. Cantwell

Egaeus Press MMXV

I recently received this book as purchased from the publisher.

CONTENTS – THE LINKS SHOWING MY EARLIER REVIEWS OF THESE WORKS WHEN FIRST PUBLISHED:

The Face In The Wall

The Filature

Offal

The Notched Sword

Beyond Two Rivers, A Symphonic Poem*

Only For The Crossed-Out

The Curse of Desert and Flesh

Moonpaths of the Departed

The ‘Kuutar’ Concerto

Symphony of Sirens

Orphans on Granite Tides

*first publishd in my own published Book of Classical Music Stories (2012)

Introduction by George Berguño

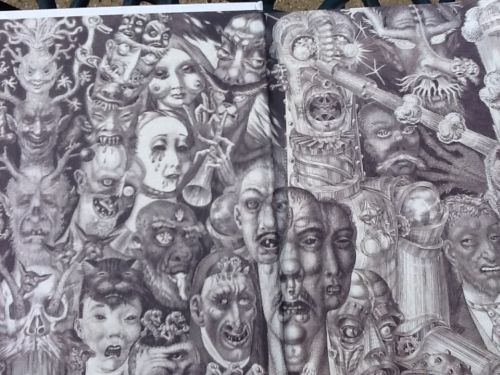

Above cover and endpapers: Eduard Wiiralt

Internal artwork by Charles Schneider

.

My previous Egaeus Press reviews HERE.

One day, I may real-time review the whole book, by (re)-reading all works and, if I do so, that review will appear in the comment stream below.

Filed under Uncategorized

A densely textured, like the prisoner himself, text about a prisoner’s ‘enmuralment’ in the city wall (from his own point of view), punished for a crime (I don’t think he tells us what the crime is) to sit out what becomes a longer period perhaps than he would otherwise have lived, for reasons one infers from the text he is imprisoned within is to to do with the city, its passing strictures, plagues, wars, and petty graffiti and taunts upon his person, et al. I was intrigued by many things, such as some of the city’s outer walls having prisoners within, too, but with their hands and arms left free, as if to fight off marauders of the city that they have become. With our narrator, we can only ‘see’ his face, a solitary one unlike those on the book’s endpapers. His crime? Punished retrocausally for outliving the city itself? And creating by his narrative words this upstart of a replacement wall of text itself? A cross between Clark Ashton Smith and Lord Dunsany, well decanted by Cantwell with new flavours that are himself.

============================

It seems meaningful that this story follows one with ‘Bloody Silk’ in its title…

With the vessels, vats and cocoons of a silkworm farm in China, this story is, for me, with only one other story in the book yet to read, the most memorable vision so far and the one that, I suspect, conveys the soul of our Ewers with most force. This is managed by giving us the chance of reading, with carefully, believably increasing horror, the discovered diary of a German man visiting China as a representative of a firm supplying filature equipment… Despite misgivings, the German repeats sexual relationship indiscretions (here with a feisty filature-working Chinese girl) that seems to have caused his German firm abandoning him here in China in the first place. The Christian converted Chinese man in charge of the filature takes his revenge for this and the diarist’s other misdemeanours… I can’t repeat the intricacies of the denouement here, but it is a remarkable interwoven metaphor of Christianity as transfigured, in (partheno)genesis, by that very interweaving. I don’t know if this story won a literary award for 2011, but if it didn’t, it deserved to do so for its own seemingly autonomous transfiguration from a traditional-seeming horror-pulpish plot as if written in the mid-twentieth century (exciting and enthralling as a plot in itself) to a newly inspiring archetype or myth for our times. From vat to silk.

“…though they often resisted it, all men stood to benefit from change –“

“No room for history in a hoard. They are altars to an immobilized future, built out of the dead and conquered past, on which are offered futile prayers for an undisturbed eternity of acquisition and neglect.”

If you can conceive of the most rarefied portrayal –

of hoarding as a horrendous tipping-point, and, after you have seen all those unbelievable TV documentaries about individual hoarders and their mind-boggling possessions as hoards, then if you can imagine a portrayal spiritual as well as utterly ‘deep’ in all senses of that word, with you as reader feeling implicated as the multi-consistency rubbleshooter, too, simply by reading about it

– then this tangled cocoon of symbiotic pollution and polluted as extruded by a filature of text is that portrayal.

Has echoes, too, of the burying of self in the first story’s time-layered city piles…

“…the story was no different now, nothing really happened in its pages, but I had changed…”

A fascinating diary as a story as a diary as a story, involving writers Bruno Schulz and Witold Gombrowicz, involving 1939-1941 MittelEuropean matters, race and writing, that seems to involve imprisonment in history as war (history against history as halves of a whole?), trapped like a face in a (ethni)city wall, and later released as the offal hoards of self, that can be halved without changing or blaming each half of self (or absolving each other)… An absurdity for all histories, with puppets as puppeteers, and vice versa. When does absurdity cease and wisdom begin? Upon the cusp of this book? Thinking aloud.

I wonder if my previous review of this story a few years ago resembles what I have just said in any way? Half and half, I guess.

“…I had never had any gift at all, and that anyone who encouraged my writing — the publishers who wrapped it in lurid covers, the bored young students and clerks who bought it hoping for a glimpse of blood or flesh, the distracted critics and poseurs like Gombrowicz — did so for trivial, evanescent reasons of their own or more likely no reason at all.”

“Hand-painted in rich and atrocious acid hues, it depicted the President in some historical mode of costume riding at the head of a horde in peaked helmets and armed with bows and curved swords. Around the border, scrolls and florets of a quasi-baroque type clashed with Islamic calligraphy.”

There are some stories that, however many times you read them (and you will understand why I have already read this one several times), will always produce something new, indeed something so radical as well as new, it becomes its own metamorphosis, preternaturally providing a literature that is akin to all great non-programmatic ‘classical music’ such as symphonic poems. This work relates to three of my favourite pieces, Sibelius 4 and 5, and Shostakovich 4, and a new, as yet unheard, symphonic poem that is ASIF it is this story as a symphonic poem itself. Hoards now become hordes, walls with faces like the first story and the endpapers and bookcover, a wall that is the orchestral performance that becomes its own music you conduct as the story’s reader as maestro, then, as conductor, cloying through it, towards a vision of Islamic history that has really only become obvious in the last year or so (a new state) since this story was first written before its publication in 2012?

“Men were satanically clever animals who reveled in the exercise of their guile beyond the point where there was any gain to be had. In this they formed a whole with the stupid, striving, wastefulness of creation, its uncountable stones and clouds, the irreducible shapes of bare tree branches in the fall.”

Hordes and hoards, and, now, having just re-read this story after reading for the first time its author’s OFFAL, new piles of osmotic books fall into now neat rather than disordered place in the piles around me, having fallen down a chute into this Kafkaesque basement. (Realbooks (not ebooks) are the only ones that can be injected directly into the reading-vein, I propound.)

I cannot do justice to the weird reality in the guise of historical satire going on above this basement, because it no doubt means something different to different readers and, so, why cross-out or redact your understanding of it with mine? You should just read what has now become, to my mind, a classic story.

“The secret policeman never traveled alone, but those who accompanied him were rarely seen — they were presences on the margins of rooms, whisperers in stairwells, shapes behind pebbled glass.”

An extended prose poem combining the ‘metamorphosis’ I mentioned earlier within a story (here ‘the two rivers’ converge as human and animal ‘offal’?) and within ‘the half horse / half man’ in The Notched Sword – becoming an amorphous centaur? I do not think I have read such perfect prose perfect for what it describes, almost beyond my imagination of anyone being able to write such densely pitched coagulations of readable text. And I don’t say that lightly.

“What if I could show that, thousands of years before man wrote, he composed music?”

I know it is a spoiler, but it becomes clear towards the end of this lengthy tour-de-force that the narrator is Anton Webern, my favourite composer. As I re-read Moonpaths just now, I felt sure that it had redoubled even what I remember of its incredible power when I first read it – and reviewed here – in 2011. But, since then, I have read Dr Faustus by Thomas Mann, Adam Cantwell’s own Two Rivers story (reviewed above) and (for spelunking cosmic horror references linked to Moonpaths) fiction by Scott Nicolay. (In passing, if Cantwell has not read Nicolay, and if Nicolay has not read Cantwell, then I would recommend each to the other!)

I shall now have blind confidence in my 2011 self and advise you to read (at above link) my original review of this crazy genius Moonpaths story because I am sure that review will improve on how I might be able to express it today, as I am now older and frailer, as well as now being further mind-altered by Thomas Mann’s Faustian version of atonal music madness!

An interesting comparison with Cantwell’s caving scenes is the quite different scene (quoted at that link) of Mann’s exploring the sea like Captain Nemo…

“To tread the ground of myth, however, after Wagner’s masterpieces, [to retail the myths of far Finland to a jaded Decadent Europe,] did not seem to be the way to make his name. What if, instead, he could conjure the old gods onto the city streets through which he staggered and dreamed?”

Like Webern in the previous story, here we have the great Jean Sibelius taken out of his comfort zone. It is manic, it is magic. But this re-reading of it makes me wonder what is an artist’s true comfort zone? What the artists THINK is their comfort zone? Or what is TRULY their comfort zone?

Where madness fights sanity and destructive tradition becomes constructive avant garde, or vice versa? Decadence as Growth? My previous review in 2011 will again no doubt provide a more useful review of this story than this one, as I think I have now entered too much of a confused comfort-zone myself since 2011, my head on the tracks awaiting the locomotif of fate, or in Sibelius’s case, not the tracks, but the staves.

“I have never seen anything like it, and I have been to the Alps. I looked down and watched the clouds change in the wind. The white was so pure. They were like hills, mountains…”

I have not yet revisited my 2011 review of this story, but today the work seems to be an astonishing premonition or metaphor for the two aeroplane events that have horrified and taunted our imaginations since this story was first published: i.e. the Malaysian vanishment and the Alpine imputedly Ligottian ‘suicide’. So, this Q&A session takes on quite a different slant, as well as still musically variating upon the historical geo-political situation of Soviet Russia and Europa, in interface with avant garde aesthetics versus traditional in music. That is all I can think to say about it at the moment.

“I mistook the letter-forms, the gamut of rational and constant gestures — the mere code — for the wisdom. Turned this way or that, they might fall into new and revelatory configurations or into nonsense.”

…this novella, this whole book?

This novella, as a microcosm and metamorphosis of the book it ends, is probably the most difficult work (that potentially seems to have within it a solution to its difficulty) that you will ever read. Or re-read as I have just done now. I have of course added the new context of the whole book, and I recognise that this author has now placed me on one of his ‘edges’ of comprehension. I have now factored in the faces in the wall, the new chutes to books of basement, Verne’s and Mann’s submersible worlds, [and my own (“the earth’s surface is not a great carpet…”) where hawling and Hawler is just another name for Erbil as another pivot of world history] … like the suicidal balloon flight over Reich-threatened Paris… It is also a story of more ‘crossed-out’-ness, with texts missing, rich men’s conspiracies of books and history, and extrapolations upon a nineteenth century Fort Ross when Russia occupied California, and a mythically created submersible land, filtered through the texts of a showman masquerading as a native Indian… There is no way I can even hint at what sort of thing you have in your hand when you read this. You just need to let the whole gamut of mock-möbius contortions flow over you. I suspect it changes the shape of the reader’s physical brain as well as its contents. It is quite capriciously amazing. [Sorry that my pointing out (in my 2013 review here) that there was a typo on this novella’s last page has been ignored.]

This book is about and by mad genius. A Weird Literature classic.