Skein and Bone – V.H. Leslie

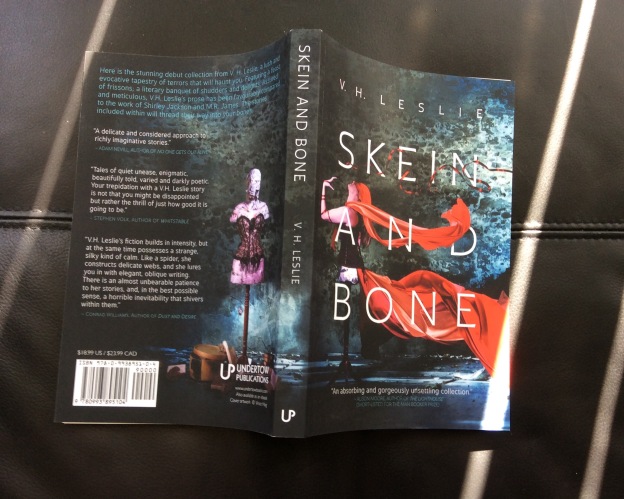

This collection is published in 2015 by Undertow Publications. My previous real-time reviews of books by this publisher HERE.

Book purchased from Amazon UK.

When I real-time review this book, my comments will be found in the thought stream below or by clicking on this post’s title above…

Namesake – V.H. Leslie

“…it was about finally being shot of her name.”

A story with an engaging plain style about a Plain Jane who is known throughout by the initial J that makes me strobe between her being her and I as I enter her world of her Internet dating, and a dancing club’s spiral staircase and a rope ladder coiled up in the supposedly empty “attic space” and those who inhabit the Internet, the crossing of names with nicknames, double-barrelled named marriages, Rapunzel, and Hitchcockian birds from the air now enclosed, birds from an air that literally and literarily becomes Jane’s Eyre. Or Eyrie. A plain style that packs a truly effective and arguably complex horror punch. Eerie as well as visceral. And messages for all us ‘puddle-jumpers’ in modern life.

With telling echoes of Leslie’s own Cloud Cartographer story.

“Laura reached for a leather-bound copy of Proust’s LE TEMPS RETROUVE…”

I think the clue is there, and the cakes and cake stands. The main character in that huge Proustian novel had Proustian selves that were independent of each other as the central character went through life and looked back at each autonomous self that he had once been. This concept is extended here by the characterisation of two sisters, the older one more flighty and less bookish than the younger, as if two halves of the same person.

On one level, a satisfyingly page-turning, disarmingly simple narrative of the two sisters In France randomly leaving a train at a random station to visit a chateau one of them had just seen in a magazine, a place that turns out to be an eerie place.

But there emerges a mixture of an almost doorless library of books, and corseted costumes, mannequins, an overgrown garden, dreams of birds and a strange housekeeper perhaps becoming a symbol of the original Eve following an earlier vision of Eve, the Apple and a sinuous serpent, from which situation all selves have been created, without normal birthing, as selves of the universal self, symbolised by beautifully frightful mutations of the boned corsets (or the storybooks or library which they are trapped within), mutations as red web-like skeins shelling out or dividing further selves toward new storybooks, in contrast to the snake releasing the birds to fly….only to swallow them again. As the story, I infer, finally threatens to swallow our own current selves after our short flight within it.

“Its skin developed a milky film of mucus that seemed to encircle it like ectoplasm,…”

The pond seems to be in some symbiotic relationship with Annette’s dead husband Fergus who used to look after servicing its filter etc. Filters can work both ways, I guess, and there are some very poignant moments in comparison with the cause or nature of his death, vis a vis Annette’s dreams, her three daughters wishing to make a patio over what they see as a stinky pond, her grandchildren, a net or membrane like a scab, all such factors in interface with this story of a ghost that becomes more of a (brilliantly described) fish creature than a ghost, with, echoing Skein and Bone, its own margins of ‘self’ accretively divided from its environment, “Solitarily haunting what was left of the pond.”

“About time to exorcise those extra pounds she’d put on, which she inevitably did at the beginning of a new relationship.”

….as if to flay herself for full sensitivity of being touched, absorbed?

Her ‘baggage’ is under the bed, but what else is there? An amusing short short that is a fable with a moral regarding accumulation of objects and people throughout life but with the inevitable, if intermittent, preserving of a solitary self.

Family Tree – V.H. Leslie

“People shouldn’t be so scared of embracing their bestial natures.”

This is a telling outcome of the gestalt of ‘Black Static #27’ stories in the form of, for me, a hilarious account of the human-animal ‘chain’ in the sheer explicitness of reaching its own Bestwickian mid-‘churn’ of a “missing-link” – here upon the brink of some challenging form of ‘Cuckoo-Spit’ stickiness and symbiotic feral ‘were’-ness. ‘The Good Life’ sit-com’s fashionable mock-sophisticated natural food and self-sufficiency – in family form – taken to the logically absurd gap-jumping along its chain of cause-and-effect, with the schoolboy protagonist (on the brink of going out with girls) coping with the reaction of his peers to the sudden revelation (after their ball is kicked into the long grass) of a highly embarrassing incident in one of their regular “parent share” evenings at his own house (NB: the Jacob Ruby story’s own ‘parent share’ concept as an illuminatory comparison!). Yes, hilarious: potentially repulsive, too – but with a skilful sense of thought-provoking seriousness as it touches on ‘mental illness’ in a similar way to ‘The Churn’ and, familially, to the Jacob Ruby story with its treatment of bodily-change and family-links via a semi-genealogical ‘Tree’ of sloughed-off connections. The ending allows our protagonist to make a sudden absurd jump which is, in the context, perfect: making me, in a vaguely metaphorical parallel way, proud openly to read Horror fiction, whatever people think of me. But does Gord Sellar’s ‘Frankenstein’ conceit come into it?

Another great statically dynamic group of blackstories. (21 Feb 12 – two hours later)

“I don’t understand why stories have to hack at time so much, fancy flashbacks and leaps forward in the narrative is plain and simple cheating in my opinion.”

I cannot complain in a similar manner about this story, although it exploits the devices in the above complaint by one of its own characters! This is an inspiring story of a man who feels he is responsible for time’s keeping to time, and his life is spent – between brief sexual encounters – using clocks, watches, hourglasses and special fabricated sand running as a source of time, and bending his own habits into routines to match such disciplines – until he meets Helen, a woman with whom he begins to have a deeper relationship, although at times their love making is akin to his manipulation of a fleshy clockwork within her, leading to a horrific climax.

I can’t do justice to its plot and style with that summary, but I do recommend your reading it as well as a story by Elizabeth Bowen (probably my favourite of her stories from which I provide a fulsome quote below). The Bowen story is quite different from the Leslie story; it is rather an inverted illuminatory form of it.

The Leslie story is, for me, a masterclass in the realm of what I have long called ‘the synchronised shards of random truth and fiction.’

———————

The skeleton clock, in daylight, was threatening to a degree its oddness could not explain. Looking through the glass at its wheels, cogs, springs and tensions, and at its upraised striker, awaiting with a sensible quiver the finish of the hour that was in force, Clara tried to tell herself that it was, only, shocking to see the anatomy of time. The clock was without a face, its twelve numerals being welded on to a just visible wire ring. As she watched, the minute hand against its background of nothing made one, then another, spectral advance. […]

‘I’ll tell you something, Clara. Have you ever SEEN a minute? Have you actually had one wriggling inside your hand? Did you know if you keep your finger inside a clock for a minute, you can pick out that very minute and take it home for your own?’ So it is Paul who stealthily lifts the dome off. It is Paul who selectsthe finger of Clara’s that is to be guided, shrinking, then forced wincing into the works, to be wedged in them, bruised in them, bitten into and eaten up by the cogs. ‘No you have got to keep it there, or you will lose the minute. I am doing the counting – the counting up to sixty.’ . . . But there is to be no sixty. The ticking stops.

From ‘The Inherited Clock’ (1944) by Elizabeth Bowen

“If you were to shout out here, your words would be snatched away, hungrily absorbed into the void. The muffled syllables would lie dormant under the ice, waiting for a thaw that never comes.”

That quote seems to have a frightening resonance with the considerations I made above about the Proustian self – this being an SF-like extrapolation featuring a mother and daughter warm inside looking outside at Winter’s snowmen, a poetic claustrophobia mixed with Christmas excitement, an extrapolation, indeed, of climate change, a musical ‘dying fall’ of eternal winter mingled with hybrid snowmen ineluctably emerging from or merging with the traditional snowmen childhood once made with carrot noses etc.

I notice that the page numbers in the table of contents don’t always relate to the actual numbers of where to find the stories. I was wondering if this relates to the time-slips mentioned in ‘Time Keeping’? Or reference self and actual self not exactly synchronising?

There are a few of VHL’s own nicely naive illustrative sketches in this book. The book’s cover is by Vince Haig.

“There was so much blue in the world, she’d never noticed it before.”

A truly haunting story of a woman, having been widowed by her artist painter husband, staying at a hotel and discovering herself in a room – not of magnolia and tired flat pack furniture as she expected – but of various shades of blue. Also bearing on its wall a painting of a woman and a crow, a painting by Picasso.

This is a strong portrait of Proustian selves not only of people but also of things, rooms and places.

The fact that the hotel is called Hyde Hotel is, for me, no accident.

The inter-mutual sucking of colours in pecking orders of strength and will power or deliberate passiveness between people as well as selves within each person.

The vision of an orgy towards the end is a striking case in point, which I will leave you to read to discover its significance within the interpretation I have set out above in a broad brushstroke.

This is an original concept of the ‘blue mist’ as another form of ‘red mist’ (red mist as an expression of sudden, implacable anger.)

I’ll leave you to guess what the blue mist represents.

I am left with one question: was the Picasso a print or an original?

Ulterior Design by V.H. Leslie

“…the carpet laden with paper strewn like a hundred glittering leaves.”

The old ghost-story ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’, for me, concerns Feminism, when verities of gender and loyalty were more fixed, with period pains rather than the more positive pregnancy in this new Wallpaper story because, here, it is indeed a different world where, almost gratuitously, both male and female need to fight back against an indifferent rage of reality, as well as against each other willy-nilly in a form of inversely self-destructive ‘Humanism’ – and, effectively mixing images, within a seemingly modern casual relationship that now promises a child, this story deals with today’s immersion in material possession like property, flanked by frostbite / brittle shelter by glass, bird aggression (portending a plague of Bird Flew-mindlessly-into-glass where even nature has become the enemy rather than a nurturer?), and this is life as we know it, internally and externally not just road-rage but the road to life-rage itself. [The wallpaper here also reminds me personally of the carpet motif in the forthcoming ‘Nemonymous Night’ in a strangely oblique and coincidental way.] (26 Feb 11)

The Cloud Cartographer – V.H. Leslie

“Lucy couldn’t imagine the world like Ahren. She couldn’t see it in a map […] she couldn’t see the bigger picture.”

Holbein’s Ambassadors have grouped and sorted their objects, many of them used in early terrestrial and celestial cartography and, for me, strangely , by some chance synchronicity of random truth and fiction, that painting has now seemed to act as an inspiring backdrop to this poignant story of grown-up Ahren and some past events concerning his sister Lucy that become clear by the end of the story as he maps the clouds – not really dealing with these clouds in a fabulous or absurdist fashion as Rhys Hughes’ protagonists often famously do in his inimitable style but, in VH Leslie, actually walking upon them, exploring them in a credible form of that deadpan way of expression exemplified by the previous story, exchanging real ground for the variously constituted (tenuous or more sturdy) ‘cloudstraits’ that have prayer flags and other odd denizens whom he meets. A sense of the Piligrim’s Progress. Deadpan and straight-faced, yes, as a literal hanging suspension of disbelief, but with yearnings and visions that add a sense of spirituality to his task. This story will be sure to stay with me. It has together a firmness and gossamer quality that escape many who strive for such a blend.

“There are no footprints in the clouds.”

Preservation by V.H. Leslie

“That’s what she had here; her own curiosity shop.”

I read this story in a single supreme semantic-symphonic sitting and it was distilled perfectly into my brain in one fell swoop almost without notice: but much more went in than I could ever credit at the time of reading it – a few minutes ago – with pickles and preserves and post-rations and lactations and sadnesses and failing marriages all lined up in each set of printed word-jars along the larder shelves: reminding me of idyllic adverts from the Fifties when my Mum and other Mums had their flowery, floury aprons on and, fresh from turning the mangle, gave us makedoandmend recipes for their menfolk fresh from the war, any war.

It was only later when men went on cricket trips, instead of wars, that they were painfully bruised skin-thin by hard red leather balls which later got buried in some poor woman’s womb ready for bodily cooking. That and more came to mind.

It was almost as if Lloyd’s sea-woman creature had been cooking McIntosh’s dodgy shellfish.

The ending is deeply poignant. Still is, never ending.

“…and he told her about the snake and the apple, though she already knew that particular story.”

A parrot called Poe to match the earlier crow in the Picasso, and here, too, a raven glimpsed and the main character’s name as well as ‘raven’ are both almost embedded in the word ‘Nevermore’ given a lost letter, while this story’s ‘Dr Jonson’ of the famous dictionary has a lost ‘h’…

A story that appeals to me in one regard of words being tangible objects, with powers beyond the page where they are written, here planted by the wordsmith Vernon in his garden where he also has rhapsodic liaisons with a young girl called Felicity (and later in his bed), a girl who we assume gathers in age – as well as in scrabble wordage – as the story goes on.

I did not fully understand this story but relished much of its wordplay. A story a bit too inchoate for my taste.

“Everything made more sense as a pair.” This, together with a reference to the book 1984, seems to resonate with the book’s gestalt so far.

“Ava couldn’t conceive of keeping the urn anywhere else. Prue liked the piano apparently and was especially keen on Liszt.”

The ‘story’ or narration to sell something like an antique, here to impart a house.

Sometimes with fiction the reader needs to remain passive and not worry about actively seeking messages from the unfolding events, a sensibility which is part of the usual nature of my dreamcatching of books, I hope. This story – like perhaps this whole book – needs an even more passive, non-preemptive approach, allowing the messages, after finishing the reading of the work, to create their own tapestry, before you even stand back to look at any gestalt. The widower Terry who makes no secret to himself of how glad he is of the death of his estranged wife Prue. The over-large house, one with a silent piano, where he chooses to live with his teenage daughter Ava, a girl who is at one moment typical with loud music in her room and beefcake posters on the wall and at next moment learning to play the piano in sight of the urn containing Prue’s ashes. Prue’s living sister, almost her complementary half, like Laura and Libby earlier in this book, who teaches Ava the piano. Ava’s maturity in being able to argue the case for Cage’s 4’33” against Terry’s scepticism. The agonising memory of the dead body being primped and primed by undertakers for viewing in the coffin, a mixture of memory of that person and of a frightful deathmask. And much more. All coming together, for me, into a wordform of Munch’s scream.

None of it truly makes sense separately. None of it makes sense indeed even as a gestalt with the inchoate images and emotions and hidden nightmares but each desperate for connection with the other into a tapestry or skein that you simply know will eventually come, as it begins already to come as I think about it coming, as I write this about it. The space under the bed. The piano performance and its deadpan audience. The tacit music box.

(Although most people know that “4 minutes 33 seconds (tacet)” is a piece of music composed to be silent, few know of the four and half page story in Nemonymous Two in 2002 with a similar title, what has turned out to be the world’s first blank story.)

“The Lady of Shalott at least had her tapestry to keep her busy.”

This is an exquisite coda to the book’s stories as a gestalt that I have read over the last few days, and to its stories that I once read a year or so ago that still reside in my mind if in a less defined form, with such elements of misty memory and focused immediacy creating, I claim, a theme-and-variations on time keeping and time losing.

A blend of the senility into which I must enter if the body doesn’t get me first, like the lovely time-keeping British lady in this last story, one with a beautiful Japanese ambiance and tone, that passiveness I spoke about above, in her Japanese tower able to view all points of the compass, and with a memory of her time-losing mother in Britain in a similar tower, then the war that affected expatriates in Japan, the outcomes of her marriage, a marriage ever celebrating its Paper anniversary, a husband with whom she made decisions by the game of paper-scissors-rock, as this whole story celebrates paper, the lady’s accreted collection of 1000 origami paper cranes not necessarily the lifting sort but the feathered sort (or perhaps both?), paper’s messages and paper’s cuts (cf the quite different but equally significant paper birds in Cate Gardner’s recent kindred spirit of a Black Static fiction that I very recently reviewed HERE), and snow creating a window’s blankness and perhaps, I imagine, a silent snowman, too… And a different purity as this lady’s ultimate Proustian self?

This highly satisfying book is its own complement. A game of skein or bone.

end