WRAITHS and ERITH

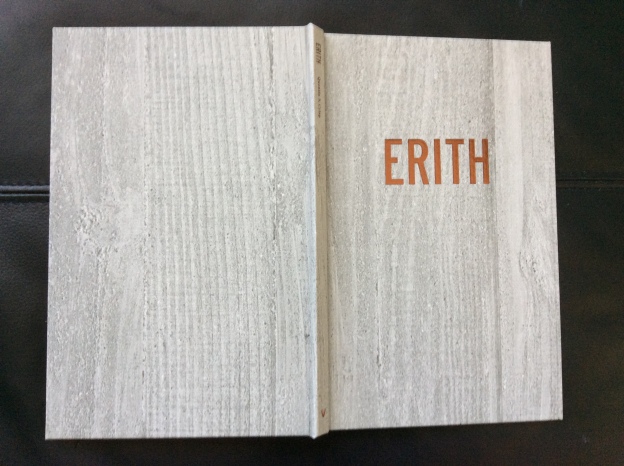

I have just received the two books from ZAGAVA

ERITH by Quentin Crisp

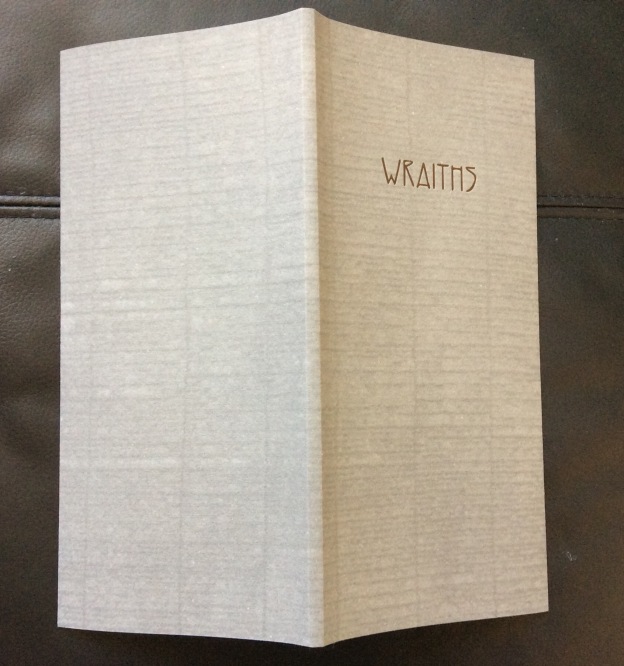

WRAITHS by Mark Valentine

My previous reviews of ZAGAVA books are linked from HERE.

…and of Mark Valentine works HERE

…and of Quentin S. Crisp works HERE.

If I real-time review these books, my comments will appear in the thought stream below or by clicking on this post’s title above.

The new publication on the right seems to be a revised second edition of the edition on the left, the text and nature of which I have already reviewed HERE. The new one (mine is numbered 7 out of 50) has an even more tenuous quality that befits its wraith-like slim volume status that is central to its mythos. Both have their luxurious moments, though. Both will vanish before you can read them, I sense, like ghosts of books. A verve with a nerve.

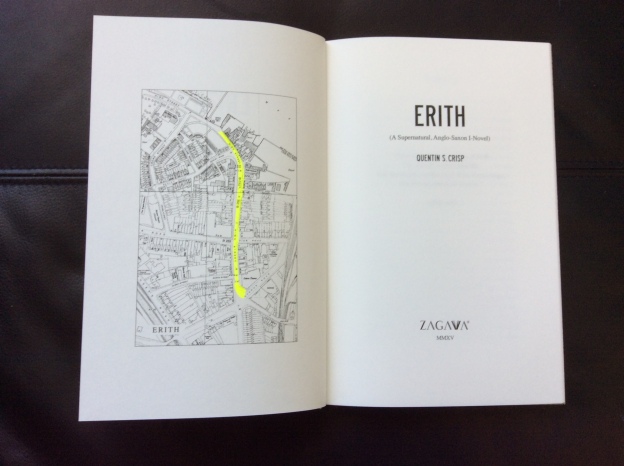

(A Supernatural, Anglo-Saxon I-Novel)

By Quentin S. Crisp

“…without this little patch of Erith I might not be putting pen to paper at all.”

The Literature of Hesitancy, I always find this author uniquely radiating on stiff paper pages that no Kindle could manage to convey, dwelling on the pronunciation of this South East London place, its spire, its Christian cafe bookshop…

The narrator is looking for the Town Hall to claim Housing Benefit, and I can empathise with the mazy wordy clause structures of heuristic Hesitancy and its maze of subways where it is easy to get lost, with strange mentionable areas cut off by such subways. I’ve been there, done it, got the Tea Shirt. Except not in Erith. Yet.

“At least three people – I could name three now – have warned me that I weaken my writing by including too many literary allusions and self-conscious references.”

When I advertised this real-time review of ‘Erith’ on my Facebook page, one of my ‘friends’ claimed that Erith is the least likely place on Earth to be deemed ‘supernatural’. I then took a look at Erith and Earth and the ‘patch of Erith’ in this dual carriageway underpass…

Meanwhile, this text’s heuristic hesitancy continues apace with a style to die for, as we absorb the narrator’s impression of the insides of the Town Hall that he eventually finds. A masterstroke in description, making a heuristic hesitancy a new-found literary tool that actually works well, despite that quote above.

I see the reality and superreality of such a local authority office embedded in buildings not originally meant for them and the nature of the beings who officiate in them at various levels of pecking order – and the internal accoutrements and decorations range from Baronial to Whovian. And the electronic duties or sought fealty entailed by screens today. No time to be hesitant with paper forms but STRAIGHT IN THERE.

This text also reminds me of the scavenging amid a palimpsest London laced with dark existentialism of another book I reviewed recently HERE (‘The Haunted Sleep’ by Jonathan Wood.)

“Whether Pagan, Christian, or some other thing, my spirit had been excited, my imagination set astir.”

Although that quote does not demonstrate the phenomenon, there are many en dashes in this section of text. One short sentence with three of them, for example. They seem to replace colons or commas. It is a good job I like such use of en dashes, although, defiantly, I will not use them in this review. Exploring this particular text, for me, is like examining the behaviour of the observed customer in the Town Hall and the officious woman manager in charge of the young men employees, so young they look like boys and, then, after leaving the Town Hall, trying to negotiate one’s way to the spire, having a densely packed array of wordy thoughts about this church and perhaps about joining the church as a vicar because of the nature of the mud and trees and their smell and sense of shelter from the spatters of rain, after passing through the “thewy lintel.”

The reading of these passages is just like that. And as in all my reviews I pencil in the margin of the books I am processing in real-time, just like this narrator is doing.

No sarcasm intended, but I am enthralled, and I intend to continue slowly savouring it again tomorrow.

I may not continue itemising the plot for fear of spoilers.

“The true sources of life have been buried.”

There is something sad here, not now so much a heuristic hesitancy, but more a bookish bewilderment, as we share the narrator’s miserable circumstances of living quarters, and the nature of itches and floaters. (I can certainly sympathise with the floaters (a swirl of which have, at least twice, abruptly and alarmingly attacked one of my eyes in recent years) whilst I can empathise with the miserable living quarters and the question of itches). The text evolves as marginally opaque or clumsy, deliberately so (I infer), but also , in a paradoxical miracle of style, marginally smooth and clearly evocative. I don’t think you will ever read another book quite like this one. It makes the reader feel somewhat different. Not sure of the nature of this new somewhat but I am hovering on the edge of transfiguration into someone else, with the matters concerning the Chesterton book about Francis of Assisi, one of the three books bought in the earlier cafe bookshop. I happen currently to be reading Chesterton’s Father Brown stories and real-time reviewing them HERE. I consider this to be a striking coincidence, and strengthens the surreal and philosophical eye-opener quality of the Father Brown stories that I had already noted, but also of these two Chesterton books now floating about together in the ether of my consciousness.

There is something inescapable going on here, drawing me into it. Something methodically and naively clever. Such a detached soul encircled or oppressed by ‘them’ – which brings us back to THEIR disguise as ERITH?

“Hell, I thought, and Heaven, are the same thing.”

“When a task makes me especially anxious, I will often try to cope with it by breaking it down into stages like this.”

Heuristic, hesitant, passive, bookish, bewildered, anxious (encapsulate all that as ERITHIAN?) – I, too, feel I am Erithian, hence my methodical real-time nature of episodic book-reviewing like this one.

Intrigued by the nature of this narrator’s Erithian reaction to the bus numbers in the Erith area of Earth, and that none seem to want to go to Erith as a destination.

The nature of the underpass, too, is wonderfully described (can’t do justice to it here, rarefied, down-to-earth mystical, shangri-la?) and the special quality of cut-offedness reminds me of when being on a Narrow Boat on a canal within a city…

The notebook phenomenon of collecting what-you-hear-people-saying, where middles are more approximate than ends, at least partially explains what I was trying to describe earlier of the appealing awkward-smooth nature of this book’s text. And its en dashes?

My caps and squared-off word below…

“How does one ever describe a colour, a taste or a scent, especially if the method of comparison to other colours, tastes and scents is disallowed? Only by THEIR effect,…”

“They [people] do not fascinate me because of THEIR behaviour, but because of THEIR atmosphere.”

“His grip on English words was firm, but curiously at the wrong angle,…”

Erithian’s encounter with an East European beggar, where generosity is generosity whatever garb of intention it wears, I guess. Change and relief.

Erithian now adds – to the previous list of epithets above in my review – ‘self-hatred’, plus a complex naivety and a belief in epiphany as a sort of möbius loop – unlike the train’s loop from Erith to Bexleyheath (where he lives) because it is resolved or jumped after rumour and pointing. Trains and buses in London, a symbol for what looks out from them: everyone’s ‘I’.

That “Anglo-Saxon I” of this book’s subtitle?

I loved the ineffable oasis of ‘Nothing matters” where the earlier coordinates mentioned in this book are conclusively triangulated at least for a nonce – by dint of my own triangulations of dreamcatching it here? (Four en dashes slipped in above!)

“There is a sense in which my story is already over. I have completed its arc inside myself and it only remains to go through the outward motion of a dying fall -”

…but one senses that this authorial voice is just as likely to remove a paragraph here and there from the pages I have already read so that any such arc is never set in stone.

I think I said earlier – unless I have since removed it as if gutting the part of a sentence that is contained between a pair of middle not end en dashes – that you will never read another book quite like this one. And I felt – and still feel – I was certainly correct in that assessment, as I reached, this evening, the end of this physically luxurious book’s text some 20 pages beyond its above mention of a promised ‘dying fall’ (a phrase I have used a LOT in my own real-time reviewing, this review included.)

It is as if Erithian does indeed come from another planet with strange, yet engaging, angles upon thought and language, while also his admitting to some misrepresentations about what he has told us about Erith and his visits to it, this last section being the third such visit so as to complete his Housing Benefit claim. He now uses the word ’empirical’ where I myself earlier used the word ‘heuristic’. What does that make me? Stranger than him? As writers, as he infers, we can only compare ourselves against ourselves not against each other. Delusions, error, fictionalisations about Erith? I believe not a word what he says about that. That’s because I believe every word he says about Erith.

Well, meanwhile, Erithian adds to my earlier list of epithets about him, like extrapolative, skilful at making imagination real – not seem real but actually real – with his walk down the jetty, the half-submerged pier, the Boiiler Room, the hooded figure he finds there, and a final encounter with the beggar in the underpass. It all rings true. As does the origin of the name Erith, in Saxon, Old Haven (Eyr Hythe). As a boy, I lived very close to an area of Colchester (Essex) named Hythe, a place that was mainly an old small port or harbour on the River Colne, a port that then in the fifties and sixties had jetties and piers. Perhaps, Erithian is another version of myself (except I don’t have a ragworm round my wrist.)

This book is a methodical struggling to overcome hesitancy and naivety, a struggle by means of conscientious trial and error, to discover why we are here and where we are going. Towards a haven called death?

This book is a supreme example of the “preternaturally secular”, to use a phrase from ithe book itself. Occasionally, there is a sense of automatic writing, but an automatic writing not like Andre Breton but one geared towards an eventually strict and meticulously carved expression of destiny as a prolonged musical ‘dying fall’.

At one moment, Erithian seems almost despairing of life, but knowing someone will publish his work (this book), and not at his expense. At the next moment, he is conscientious and disarming. A unique book, and I use the word ‘unique’ here in its true meaning, and I think, self-evidently, without empirical hesitation, that ‘unique’ is a word that I can only use ONCE about any work of literature. So, correction, THE unique book. And when I was a child there was only one channel, not three or four.

end