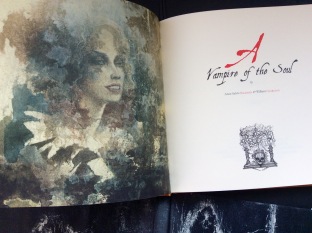

A Vampire of the Soul

A Story of Psychophagia

MOUNT ABRAXAS MMXVIIWritten by Anne-Sylvie Salzman & William Charlton

———————

Previous reviews of this publisher HERE.

When I review this book, probably during March, my comments will appear in the thought stream below…

Copy numbered 5/111. Luxuriously upholstered book with quality materials, about 10 inches square, 136 pages, marker ribbon, all beautifully designed and illustrated with dust jacket, and embossed hardback cover.

“They were moving now not with shadows but with girls, girls with solid bodies, sweating and strongly scented, smoking cigarettes or cigars;”

I don’t know where I am, on the Turkish border or in Cancun, Mexico, or wherever, as I jealously follow Photis and Ottavio, whether I be the Dreamcatcher review merchant who I am, or a character in the book who is scrying sinkholes or cenotes and luminous butterflies devouring the carcass of a horse, and much else.

I am captivated, whatever the case.

Slow motion does it, though.

Textured, visionary and poeticised.

Font, dense but enticing.

“‘….'”

“…and was now trying to write a novel.”

Judging by the amount of text available, this is also a novel, one that gets into its stride, from the viewpoint of a young lady named Photis, now in Scotland child-minding and renting to student lodgers, her previous partner Ian now dead, but today she thinks of Ottavio (who is about to take her out for dinner) and another previous man in her backstory… a backstory scenario full of cosmopolitan bright young things, I sense, beyond Brexit Britain, in various parts of the world, a novel’s novel, but amenable and character-building, where there is always at least one young character (here called Carmen), “now trying to write a novel.”

I perhaps have a good idea of the scenario, and the mix of names and types of people, and I do not intend to itemise the plot — as I no doubt enjoy negotiating my forthcoming way through it alongside the novelist — but simply to speak here of my inchoate reactions to it, some reactions justified, some possibly to turn out unjustified in hindsight, as I try to build a gestalt from its already evident craft.

My previous review of work by William Charlton (this book’s co-author) here: CANAPÉS FOR THE DAUGHTER OF CHAOS

In view of the presumed nature of this novel and of the real-time reviewing process itself, there may be unintended plot spoilers from this point onward.

I think I now know why I wrote ‘novel’s novel’ above. Not now in the sense I intended, of a fine traditional novel, a novel’s novel, as in a writer’s writer, but more now as novels side by side, one containing the other, here as empathic narrative ghost, the deceased Ian in tune with Ottavio and Ian, this ghost, also in sight of or in tune with Ian’s widow, all of whom know each other, an equivocal relationship between them, and Ian’s continued suspicions now…

This is genuinely rhapsodic material, couched by the two authors immaculately, a sort of haunted, piggy-backing Proust…?

“In Glasgow the tales it contained seemed more ancient still. The faces of my former associates appeared at my bidding in the clouds before we landed.”

[While conducting gestalt real-time reviews over the years, I have found myself in ‘clouds’ of communication of overlapping reviews. Is this process simply lucky or preternaturally prophetic? And would it work for everyone who tried it? As it happens, I am concurrently real-time reviewing two other books alongside this one (UBO where the piggy-backing empathy of souls takes place in rôle scenarios imposed by roaches and THE MEMOIRIST where the piggy-backing of souls features Glasgow and electronic communication ‘clouds’ exponentially extrapolated…)]

“It was fixed: Carmen could come –”

The machinations of the plot build up, and it is indeed a novel’s novel and perhaps a novel about a novel, too, in all senses, combining, inter alios, Iris Murdoch, Elizabeth Bowen and AS Byatt, as Photis even somehow finds reason to question her husband Ian’s demise (that cenote, again) and we learn about the potential impact of art collection and art history in her life, and other characters in a dance of intrigue around her, as she plans to stay in the Auvergne in a house where she may child-mind, but only if they have children to mind.

This promises to be my sort of adept novel to read, I can already tell. If so and if I were not a regular reader of this publisher’s works, I would have missed it.

“; it is a place where interesting relics pass surreptitiously from hand to hand.”

From person to person, too, even double of that person to double of the other person. I must say this is impressively rarefied material, and I shall now add May Sinclair and Frances Oliver to the growing gestalt of kindred writers. A gestalt with the unique core of its dual by-line above, as if conducting a symphony of modern, yet comfortably and rhapsodically seasoned, Proustianisms.

Ian interleaves his posthumous witnessing of his past friends and lovers, sometimes creating doubles (as with Ottavio) to enact some rôle scenario, a permutation or Venn diagram of destinies. And building up a palimpsest for the ensuing plot in the house in the Auvergne where Photis is heading.

As if mustering the characters, as we walk with Ian through rooms he once knew in real-time, now in a new real-time dreamcaught by this text. As if creating a Noah’s Ark for his life and loves? His dubious characteristics (like theft?) as well as his honest passions?

I keep my powder dry.

“Perhaps he was still changing. More probably it was some other Eric that was expected.”

Whether it be ‘who’ or ‘that’ was expected, Photis arrives in the now well-characterised genius-loci of the French house, with its Attic mountains. Actually, not only is Photis employed in digging into the ‘found art’ (in the sense of finding real art and finding ‘found’ or accidental art in natural configurations such as wrongly well-founded boats in boathouses or in Eric’s boxer shorts after that boat overturns on the lake). Meanwhile, other characters accrete both in number and singular substance of each, with backstories creating tensions among them, including aspersions of the late Ian’s approach to ‘fakery’ in art, smuggling and so forth. But in fiction, some of it is fake news, some not. We just need to decide, amid the panoply of drawing-room manners and machinations. I have and am genuinely entranced into and by this novel.

And who is that tall apparent non-gardener glimpsed at the end of the path?

“We drank champagne in our red bedroom with its vast bed. I sang, horribly out of tune, my little song from Rameau, ‘Pourquoi leur envier douce recompense?'”

I wonder if Ian is an equivalent of being Rameau’s Nephew?

This text now takes on the high quality of a screen Poliakoff, as we follow Ian in our rummaging through his spiritual rummagings and mischievous piggy-backings as the self-narrative haunter of people he once knew in love or distaste, amid this vast house of vast beds, I sense. And items of fine art, religious or otherwise.

Love and distaste, and sometime rage.

And flirting through another’s eyes.

I do not wish to overblow my own journey of rummage along with Ian, but it feels puckishly exquisite. Jacques the Fatalist, too?

Sadly, I may need to leapfrog tomorrow before resuming this reading experience.

“‘But poor Photis,’ said Irene. ‘It’s the Augean stables up in that attic. She’s heroic.'”

…or a female Hercules, someone else suggests sarcastically.

Having found a altarpiece up there that might indeed alter everything, fake or not, dependent on the machinations of fiction as well as its imputed truth? A magnetic heartthrob or Dolfish dolt, the biggest influence!?

The characters dance around such matters, a choreography that none of them know they are following (unless this stiff and well-bound luxurious book’s forthcoming text changes before I get to it?), including the arrival in the dance of Photis’ mother in law, an ex-in-law by her son Ian’s death, whose Greek connection gives him a posthumous longer name, as names are indeed still worthwhile to people after they’re posthumous, I guess, in the tutelary spirit of this book. We as readers should know better than anyone in the book. But do we really?

And this is a chapter that seems to contain literature’s first kiss-with-different-eyes above it.

Not that I have read all literature – unless…

“These incessant re-encounters will soon be the end of me, a prospect perhaps to be desired.”

I think this fiction work is the only one (or the first one I have personally read) where it makes you believe in your own existence beyond death, or that I might already have died but I am still myself or am one of my own “silent troops” as artificial doubles or Photes, to coin my own word.

Ian’s narration is rarefied and beautiful, especially due to his synaesthesia towards archaeological finds, towards names like Corner (later “wild cornering”) and Dolf, towards the nature of people, he once knew and may have corrupted, as Dolf claims. The machinations of the secret plans of others now are ear-wigged… But who finally is ear-wiggling whom? The mystery of who is the double of whom. Proustian selves now made tangible.

Spying upon others as the sole possession of fiction, one that can be alchemised towards truth. Possession of or possession by?

A chapter of change, other than Photis’ endemic guilt of vouching for people with names like Corner and Dolf, their complicity in something that itself does not not alter, but arrives again with solid suddenness at the end of her change to another large Gothic or chateauish house, this one in Yorkshire, for another library- or art-collation type job, making me feel she is a character from Charlotte Brontë, as well as from those other authors’ books I mentioned above. Also now a tidal bore hinting at another book, Dream of Wessex? And this change for Photis resides alongside her belief in the accretive solidity of Ian… the luxurious solidity of this book, too, with its own significantly handwritten label that I have already spotted on its last page.

The plot continues to fascinate me, and with this latest twist and turn, the authors continue vouching (as fiction authors tend to do) for their characters, as Photis does like an author’s agent within the book, now allowing us to meet (as Photis does) Mrs Sprayne in a Golf.

“And under this fake-gothic roof, I say to myself with a sigh, Photis and the St. Agnes are reunited: two beams of light…”

At this St Agnes altar of altering.

I am reaching the conclusion that this novel is becoming the rich apotheosis of Ghost Story literature, building upon the tradition of May Sinclair and others.

We follow the thoughts of Ian as ghost and morally ambivalent force of our possession as well as being self-creator of our doubles, alterer, too, of our personal fates when we are undoubled. His troops and tropes.

Pursuing Photis to her own version of cenote?

I love, too, the character of Mrs Sprayne and the genius loci of ‘ungainly” Skirsby, this awkwardness of a house in Yorkshire.

“And in her tight skin I should have chattered with fear, I should like her have run after shadows, chased forms half recognised.”

“What’s biffsheets?”

An enjoyable intermission of plot movement, the contrast of the matchless previous chapter’s rhapsodic rarifications now being made with the pragmatic theatric ramifications of various relationships and conspiracies, leading to many melocomedic interactions, regarding Photis and Eric in interface with the imputed Ian, Skirsby’s Duck Decoy as some potential cenote of the spirit, the land politics of the nearby university, the machinations of the St Agnes altar piece, fakery and truth at a dinner party, the names of characters still building their own traction as words, Clotty Sprayne’s crush on Photis, the cargo ship passing by the window on the Humber, Carmen’s hilarious questions about her own unfolding novel and more. You may want to decide whether this book’s inspired ghost story of Proustian selves is now damaged or enhanced by such shenanigans. I keep my own powder dry. Future context is everything. Beautifully written, in either case.

“It is unknit, it is scattered, and it pains me more to bring it together again.”

The square brackets make it seem that Ian has earphones, watching modern characters in this chapter with their mobiles, a personal space of sound as vision, as his own moral ambivalence rubs off on those he watches, they also becoming morally ambivalent, as he watches from under the dining table, or in someone’s bed, under or over them, or inside while pushing eyeballs out in his incubic rage. Or is that imagining what I just read? Death and drowning, some of his troops surviving, some not, but which counterpart of his jealous views of Photis is real and which one dead? Only [ the reader ] can judge one from the other, better than self-denigrating leasehold Ian can judge, while not even the two freehold authors can properly judge one to the other, having consigned this ambivalently allusive and elusive text for all of us others to triangulate by reading it. A triangulation of coordinates that the dreamcatching of gestalt real-time reviews has always invited since it started some years ago,

“‘I don’t agree,’ said Photis. ‘Works of art aren’t the same as people; they’re just things. That’s something I learnt from my husband –‘”

Except this book disproves that theory, the book that created herself!

From the Humber to the Ouse (“she could not tell which way was upstream and which down”), Photis (“feeling herself again her own woman”) proceeds to another art or book job cataloging in a new Poliakoff screen, a new genius-loci, here of a Tudor house, and I continue to be entramelled by the connections between these rich, arty folk, almost an inbreeding? As the machinations continue, the backdrop of new characters in situ, others visiting or watching preternaturally or biding their time through computer or phone. A serious sense of ominousness or ianness, mixed with these new people, including the 15 or 16 year old daughter of this new location….

The aftermath or Photis’ own ‘cenote’ syndrome by the Humber, meanwhile transcended, expect perhaps for Clotty’s clingy arrival at the new location…?

“‘Risible hopes,’ I say bitterly, but at least they delude as far as the end of the path.”

You will not easily forget this chapter, as [Ian] effectively reaches the House by the Ouse. His mischief and a salacious forbidden target for sexual lust or just dreamy liaison, his troops morphing at his whim, confused landings and “painstaking notes in the margins of words and whole phrases” like my own such in the Mount Abraxas book.

This chapter probably represents one of the most haunting hauntings I have ever read. I do not say that lightly. Only experience of it will confirm this in your eyes or not, and exactly what I mean.

“…if a dead person could be mad.”

Paedophiles are indeed far more worrying than shady art dealers, and there is something elusive about the knowledge of unknown works of art cascading down through a family “without troubling the Capital Taxes Office.”

The discovery of some original Chaucer manuscript. Punting. A garden party for MPs, Bishops et al. These are are accoutrements to the plot that make their own growing gestalt, to be clinched in hindsight, I wonder. To go with the dry rot of incubation. The fruiting bodies. The possible incubation, too, of a nymphet by the lagoon. A contagion of crime. Eric feeling that once he had seen Photis with another’s eyes. And an imaginary Cellini chalice. And an even more imaginary artefact in the form of a marble elephant by Leonardo. Does fiction solidify imaginary things into real things or attenuate them even further? The plot thickens…or thins.

But there is one moment in this chapter that will perhaps stay with you more than any other. That tall Aickman-like figure again as if from some ancient Christmas-time MR James TV adaptation filmed in grey colour. This time with a dog.

Epilogue

“There runs in her nerves, thicker and thicker, something of my spirit.”

I was probably led to read these two sections together by some preternatural version of [Ian] that sits inside this hefty tome. Or at least [Ian]’s soliloquy indicates this – as if he is ‘acting’ it towards Photis as one of his created images of her, this image as a choice between my photes I mentioned earlier, created almost by the ‘lightning’ of a camera as well that of the ‘thunderstruck’ storm that engulfed her in the environs of this book’s third genius loci of the House by the Ouse. There is a dark place to be filled, either the emptiness in this bodily version of Photis or in the cenote where Ian himself was said to have perished. An amnesia … an amnesia that makes me remember thankfully not to spoil the plot for you. We just each need to collect our bespoke gestalt for ourselves. As Photis also needs to do so, Eric believes, by being able to take the ianness of Iannis from him? From herself? The epilogue factors in renewed, often hilarious, melocomedic elements from the earlier dinner party near the Humber, as if Carmen herself has taken over this novel, describing a type of various characters’ discussion at the end of a whodunnit –

who stole what, a piece of art or someone’s heart?

Superbly haunting and original ghost story, if you accept it on its own terms.

(Also I loved the burglar who failed his entrance exam. I leave you to find out about him, Clotty Sprayne’s fate and much more.)

“…makes me think that I am dying and coming back to life myself.”

end