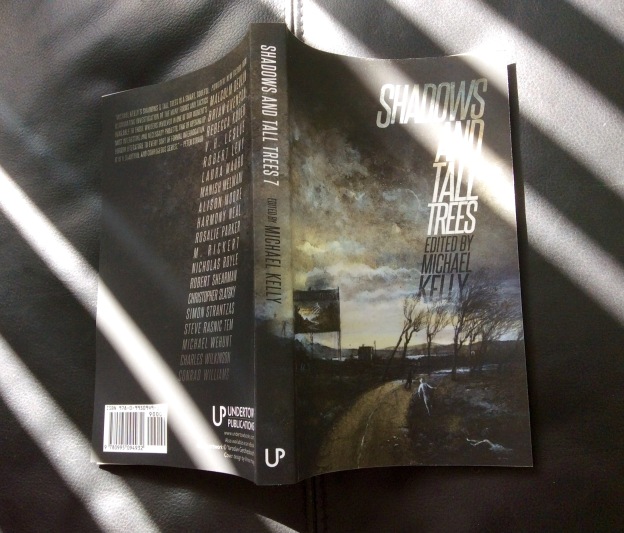

Shadows and Tall Trees, Vol. 7

An Anthology (around 300 pages) edited by Michael Kelly

Undertow Publications 2017

Previous reviews of this publisher HERE.

Stories by Brian Evenson, M. Rickert, V.H. Leslie, Rosalie Parker, Conrad Williams, Manish Melwani, Simon Strantzas, Steve Rasnic Tem, Robert Shearman, Malcolm Devlin, Robert Levy, Charles Wilkinson, Alison Moore, Rebecca Kuder, Christopher Slatsky, Laura Mauro, Michael Wehunt, Harmony Neal, Nicholas Royle.

My comments on each story will appear in the thought stream below…

Is it my imagination, but, as well as the title shaping the number 7, the pareidoliac cloud formation is of a Britain gradually about to be without Scotland?

This trade paperback edition has cover artwork by Yaroslav Gerzhedovich and design by Vince Haig.

The Cover artwork on the hardback edition, I understand, is by Vince Haig (aka Malcolm Devlin).

“You had to understand, Conrad claimed, that what it looked like was probably not what it was.”

This starts with some anangst, a sort of non-angst of astonishment that your inborn and endemic angst has not borne self-fulfilling fruit, self-fulfilling truth, a feeling with which I am very familiar, a sort of confirmation denial. Here, it is you having worked on a film that seems perfect, but NOTHING ever goes perfect (does it?) and via a skein of a few characters all of whom may be you, you as director, cameraman and lead actor (who, in one form or another of reality and rôle-playing, had separated his parents from their bodies), and you are trapped within some hiatus warren of feathery glitches that I remember cinema films used to have invading the picture from the margins, when projected.

An existentialien living ‘In Camera’, in not so much Beckett’s as Danielewski’s house of frames. (Also, any story using the word ‘annealed’ is bound to be a winner.)

“…and my brother whose suicide is not a part of this story.”

Following Evenson’s hint at Danielewski’s House of Leaves as framed for cinema, here with trees and an ‘arc of Autumn leaves’, the female narrator speaks as if the story about herself and her friend Laurel has already been filmed, and she is debating whether to divulge secrets to elucidate this filming’s own line of sight, I guess. With reference to inscrutable folk called Strangos, her guilt at once leaving young Laurel behind on Hallowe’en, to what fate? A deliciously ungraspable take upon these two girls who were not, but acted as, twins, and the whys and wherefores of tragedy, and why some words are appended with -o like being part of a song or a fey incantation. Charades, Rilke, the narrator’s father, opening the clips of purses with the sound of click beetles, the casual choices of childhood, hope as loss …. and a found orange like found art.

Was she wicked? Was she good?

This story is picked out with words of atonal music made obliquely melodic. Webern towards Zemlinsky.

“…and the small hole that once housed a doorknob appeared to be a whorl.”

“Die. Die-ty. But it was the word deity that she thought about the longest.”

On one level, a folklorish, engaging and fatally or parthenogenetically rhapsodic story of a young florist woman seeking isolation on an island near Orkney. Single and undaughtered is this woman and it is her inundation in the sea’s critterly embrace that we follow during such a break from civilisation to its hindsight inevitable, sometimes male-gory, outcome of foundling and guardian scarecrow.

On another level that enhanced this story for me beyond measure, I often think that when I gestalt real-time review fiction my whole time-surrounded life is also co-engulfed – and last week on television (I watched it last night in a recording as if in preparation for my first reading of this Leslie work earlier this morning) was a programme entitled Metamorphosis: The Science of Change, dealing metaphorically and visual-scientifically, with the comparative transfigurations into butterflies, sea urchins, starfish, locusts and, yes, human beings, as not development but genuine metamorphosis, in both directions of parthenogenesis. It also dealt provokingly with the Kafka story ‘Metamorphosis’, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, but not, I realise today, Frankenstein. Nor this striking story.

Once I had finished this relatively short story, I thought to myself: this is a classic, one that we shall all remember reading for the first time. I have now allowed my mind to dwell on it, without re-reading it, and I still think the same.

Involving a lake that seems as large as an inland sea, one that ices over sufficient for walking upon (save at its middle?), and two children, brother and sister, about their vying for the world record of reaching the other side and about the toys that they play with in their own model town at home. It is Sarban to the power of co-efficient. And something unique. I can’t do it justice here. Simply only to ask you to read it…

I shall now attempt to read it for a second time.

In itself a compelling story with a man aspiring via imagined graphic body innards towards a career as a surgeon – Jeffrey Siddall, a peripatetic labourer all his life, gradually being re-absorbed by memories, as he synchronistically merges into the area of the school of his 1970s childhood, his mates, his teachers, and the girl’s life he tried to save by amateur revivalist gutting during school dinners. Who had stayed, and who had escaped?

But, miraculously, it also follows each of the patterns of the VHL and RP stories, the metamorphosis as autonomous surgery, and the rite of passage across the lake of time back to the home where he began, to rescue himself or the girl who had vanished across that lake before him? Not Alison, but Jen?

Or Jeff? Closure as satisfying finitude or calmative darkness?

Was he wicked? Was he good?

“But among the dead, even the rich walk barefoot, thorns and smouldering ashes in their heels.”

A telling gestalt of smoking cigarettes and their resultant ashes, creating cancer, involving a son mourning the death of his father, the passing on between them of such symbiotic fallibility, and the frictions between family members in the family business, including an uncle with crocodile tears and mixed investment intentions honourable and dishonourable regarding one of the ships in the business’s fleet, wherein which ship that dreadful symbiosis was once symbolised by the onset of a first person plural narrative viewpoint, whereby even we readers are implicated in the story’s inimical forces, the water kings ourselves in attendance at that ship’s metamorphosis – a metamorphosis back to the shell-baby? Another story, like the MR, that is a tantalising grasping at meaning, and another treatment in this book of physical metamorphosis, to match that in the VHL, here towards death, gradually, while holding, at the bedside, death’s hand, implying a bodily diseasy transfiguration, from cigarette ashes, via sick mutancy, to those funerary body ashes thrown ritually into the sea, all such factors layered with another version of RP’s earlier journey across the lake of time, then homing back again…

“And so we set sail, not quite free, but no longer prisoners; something else now. We came back here, back again across the black water to Singapore.”

“Baum’s knot-holed eyes have sunk so deep into his phloem that they are hidden.”

Into this phloem or poem as prose, too.

This is another potential classic, in my view. How can a single book spoil you?

A story that takes you by the spiritual or nature-ravelled scruff of the reading neck. Ravelling not with bones but with bark and branches and foliage. It revisits and unravels and ravels again VHL’s motherhood and a foundling and a metamorphosis that I reported on with regard to that story, a metamorphosis that has spread its physical metabolic roots throughout this book so far. Here we have a woman’s bereavement with the loss of her man and now with the onset of this parthenogenesis of a ‘son’, whom she takes, as if ‘Flannery O’Connor’-infused, to the city away from the farm in whose tall grass he was born. Then her travelling with him, motel by motel, human interferer by interferer with his course of fate, and back again, as with the homing journey across RP’s earlier lake. And the end epiphany or catharsis is a masterstroke. Beautifully expressed throughout.

Tem vintage, including the inscrutable dog and its owner, and a man with the gradual onset of what many might imagine to be senile dementia after his emotional attachments have vanished, and there are now rules he now makes unilaterally about the things he owns. But his fixtures are taken away, like buildings he has lived with the view of all his life, including a vision of a fellow oldster’s hoarded detritus in a home where dementia has overtaken and cluttered simple unilateral rules, it seems.

But I also sense this work miraculously fits in with this book’s own serendipitous theme of metamorphosis (change not as evolution or development but sudden convulsion), such a metamorphosis of living beings and their property, thus giving a wily slant on the things I myself feel in my own ageing brain, things being abruptly finished, things representing an ending of the self as once unilaterally fixed: now a uniquely split-second destructible target rather than slowly tumbling away in real-time.

“Shrug.”

This story is ostensibly written for readers to shrug at, but — amid its plainspoken passages of a mother and her son, her, as it turns out, semi-estranged husband and father of her son, her son’s so-called unlikeability at school, his propensity to be bullied, if blame can be shared by bully and bullied, and the eventual ritualistic Birthday party of mass male synchronised swimming to which he is invited, the mother of the birthday boy who entraps the mother of the ‘unlikeable’ boy, entraps her in the Jesus superstardom of silky smooth wine and cigarettes, and seeming apocrypha of the New Testament regarding Jesus — this work certainly packs a massive punch. I am still thinking about it. A story that bullies you with this punch, bullies you into submission to its simple truths of convulsive, not gradual, messhiahship.

What is more it’s serendipitously built upon the pattern of birth and motherhood in the VHL and the SS stories, and beyond that pattern, a fact which makes it seem even more powerful. Foundlings, too. Now transcending virgin birth as parthenogenesis? The return of the Joseph to the Nazarene. Not to walk on water but drown in granular rebirth or baptism.

At the tontine pool’s surface level, meanwhile, it is a compelling plainspoken story, that many will enjoy, even if they end up shrugging. Without the context of this book. Another miracle, as all these stories were written separately, I guess, without knowledge of the others.

“One, because swimmers held their breath for a minute at a time and never suffered any lasting effects. And two, because didn’t babies survive without air for nine months in the womb before the birthing bit began?”

COME THE MORNING

by Malcolm Devlin

“They disappeared with such a gentle precision it looked like the climactic scene fading out at the end of a film…”

…or the end of a video game that the characters themselves have created?

Or walk what off? The previous night’s abstentional game of being offered drinks – acceptable or not? – or the porridgy mud at the end clinging to their walking shoes, to be walked off. A glass with its drink half drunk is half full or half empty. I call myself half Welsh, never half English.

Here the walkers are on some lonely Irish coast, though, not a triangle relationship, but a quadrilateral one of games makers, now on holiday, in their thirty somethings, but not yet ‘enmudded’ in marriage, children and savings schemes. A standing stone in the fog, and the ability to circle it but not to accrue curses in the process? Now two and two, separated as pairs, not the rightful pairs they set off as, but paired off nevertheless. Intriguing paranoiac kisses in case the other pair is watching them. Odd houses seen in the fog like a row of Aickman’s Russian houses. And the eventual attrition of halving the journey as in Zeno’s Paradox, half and then half and then half of itself again – forever. In the porridgy mud. A complete contrast to this book’s convulsive metamorphoses, here a slow motion tread, an evolution, a development, towards, I guess, circling monsters that the couple used to birth on screen now closing in to give birth to them – as victims?

Another devilish Devlin. Plainspoken, with held breath, like Shearman, but equally, inscrutably deep. Processes and sub-routines.

Then one on one, no longer pair on pair.

“Maybe the field would keep stretching and stretching to accommodate the distance between them.”

“Her shoes brown with mud as she slides against the wet earth, the still falling snow.”

Another Zeno’s Paradox of steps or movement, across the ‘bridge’ towards ‘agape’ (both those words used with tricksy guile in this story but with different meanings) – a transcending of a widow’s marital bereavement by Jewish and Graeco-Christian means, and of her guilt for abandoning her step-daughter, as she is taken into a crypt for an Eucharistic Last Supper as sin-eating, staying there a minute, an hour, a day and a night, then perhaps forever…

This is a powerful work, a religious ritual rather than a story, towards which the other stories seem to have been leading, by their own version of Zeno’s Paradox? Possibly one of the most disturbingly, if transcendent, Weird fiction works that you will read from the fact that it is not Weird fiction at all?

“; one moment it was as if the flakes were drifting on a level plane; the next, there was a sense of distance, the spaces between them.”

The flakes, snowflakes, echoing the porridgy attrition of progress in the Devlin-Levy. Here, a striking portrait of how I found teachers and pupils in British boys’ schools when I was at school around 60 years ago, some boys repellent and alien. Some teachers, too. And not to speak of those cross-country runs.

Following the nightmare that led to losing a pupil, Mr Shooter re-trains as a special-needs tutor. While his wife enters that pea-souper of time’s snowstorm called dementia. Invaded by intruders or those who are still left dying from the old days type of winter snow that beset our childhoods. Or is it dementia at all? Or just the God of Assembly wreaking retribution as time and life’s attrition stretches eternally towards death, but never quite reaching that destination, ever yet.

Or so it seems to me. Another Zeno’s Paradox. Or insidious Tontine.

A seminal Wilkinsonite story itself that peers intermittently through onsets of snowy italics.

“…slowly, as if she were stepping through the mud…”

A relatively short work that obliquely and satisfyingly blends today’s Brexit politics in the U.K….. and un-green industrial aberrations dulling health and the mind ……. and a theme and variations upon my own felt approaching onset of senility whereby everything seems to be too much trouble, a porridgy stigmatisation now affecting everyone, (not only those who are already old like me), an onset via the Zeno’s Paradox of clawing one’s way through mud and confusion, towards what? Tall trees in the shadows?

This work is a neat, probably inadvertent, contribution to the book’s gestalt, as well as standing on its own as a telling fable.

Not the voice, but the will of the people?

“Curse this third Thursday, bright and shiny like a slap in the face.”

I had to laugh as ‘The Third Thursday’ is the name of my long-term writer’s group in the local area, one that has met on the third Thursday of each month for many years. Where we put out what we deem to be either rubbish or genius, by turns. Today, a Thursday, is an odd day for me to be putting out real rubbish for the collectors, but I just did before reading this story. One day late because it was a UK ‘Bank Holiday’ last Monday… and we usually have these pressing duties on Wednesdays, overseen by my own officious version of Mr Warner, who lives opposite. Although he has not needed to help me make up my own required contingent of offerings and objects for collection, as Mr Warner has, arguably, helped the narrator in this story.

This story is not rubbish, it is nigh on genius. A serious contender for another classic provided by this book. The attritional duties of kerb-side (UK spelling) offerings are like the objects having an aura of William H Gass listings of objects and objective-correlatives in the shape of finely observed but obsessive literary fiction, as this Kuder is another unique version of. It has this book’s own aura, too, of slow motion metamorphosis where convulsion blends with gradualness as a character-narrator is born before our eyes parthenogenetically here who speculates putting out for collection the narrator’s preserved mother or a frozen songbird important to the narrator. I love the conceit of rubbish quotas needed for kerb-side collections, a citizen’s duty, being buttered up, rather than the frowns one often gets for putting out too much! A touching and sophisticated experience just finished, as I hear them outside at this very moment collecting my own offerings.

“I have been moving up and down flights of stairs all morning. Up, down.”

“The air was soupy like brine.”

They keep on coming. Another perfect addition to the relentlessly atmospheric slow-moving, snow flakes in the Wilkinson, here flakes of salt, even a ‘flake of the guilt’. Not Devlin’s porridge, but Slatsky’s soup as if the sea has thickened over time via various ‘mad scientist’ meters, pipes and insidious underground engines, as if recalling William H Gass whom I earlier mentioned above in connection with the previous story, an erstwhile depiction of a future Trump, Gass’s objectilia and hisTunnel built as a syndrome for some kind of Trump phenomenon and the relationship of a sort of Trump with his daughter in Atlantic City? Here, the daughter is the protagonist Cordelia, receiving messages from her dead father, and returning to the seemingly unchanged house (beautifully depicted), the house where she grew up, and a ghost is now metamorphosed from history and nostalgia in generative union.

Ungraspable, but with fixed Zeno’s paradox staying power grasping YOU instead. Here a parakeet, too, as a rejoinder to Kuder’s songbird.

Water Kings and Strangos.

“; it seemed that the world had stopped without warning and curled in on itself, interminably paused,…”

…which seems to embrace this whole book so far, ever paused at this moment of Zeno’s Paradox and metamorphosed Tontine. And Alison Moore – Kuder: “They’ve forgotten to be afraid …”

This is the story of young Sadie, told in her own words, where dryness means rain pent up awaiting almost forever for its sudden convulsion of spilling, beyond any pausing. Thirst and desert and coyotes are cursors, and avoiding men’s advances, who pretend to protect her from roaming critters. A temporary car accident and then a stowaway whom Sadie calls you as ‘you’, and you wonder if you are another foundling child as metamorphosis (rather than the slow-motion pausing of evolution) as depicted in the VHL and the SS stories, and the word ‘cocoon’ is actually used in this text about you, so as to make that link stronger. Until you realise you are perhaps Sadie’s sapphic svelte better half? Or you are that shape-shifter the men wish to protect Sadie from?

Loneliness is another woman’s living with nothing but a ‘taciturn husband’ and ‘wild beasts’…

….’subsumed by your gravity’, ‘a loose-stitched patchwork of intuition, of little stories and guesswork’. A loving svelteness upon svelteness, strange as angels, this is so tantalising, in the end you are indeed left with nothing but that very guesswork, or a “feral Mona Lisa”.

“Their heads have bowed in prayer, as if to dictate the string of unpausing words…”

Like the Levy, this is powerful Weird Fiction by not being Weird Fiction at all. Yet, it is as one with this book, even in its own rarefied and dense poetics, a path of fiction as a ritual, a blend of Aickman’s Hospice and Sarah Perry’s first novel ‘After Me Comes The Flood’, with Corddry Smith arriving in his car that is stopped just before he gets to what the text calls Furlough House, even referred to as ‘hospice’, with a group of inchoate people waiting there to help him in his ritual, either suicide to assuage his cancer and his lost lover or to bolster his own poetry that he needs to write in his Moleskine, a poetry that in many ways is this story itself. Involving overt weirdnesses like aged pregnancies (more foundlings or genuine parthenogeneses?), soporific ‘tire swings’ in the tree, found bitten apples as art, etc, and I feel I can safely say this is such UTTER weirdness it is not weirdness at all because it miraculously makes some spiritual sense, a darkly kaleidoscopic audit trail, as well as a complement to the sudden metamorphoses and/or endless evolutions of this book’s context so far as a whole. You will not (have) encounter(ed) such a work, in the past or in the future. It is here now. It is arguably an apotheosis of something many readers of it will have been seeking, without realising it. A symphony with titled and numbered movements, too. Trying to imagine in November, somewhere that “might simply burst in the green throat of May.” And removing the bookmark from yourself, as the text itself suggests. And much more.

“We die so fast. Maybe your pretty words slow it down.”

“…with a note of longing murmuring under the surface.”

I have long been interested in astrological harmonics, a synchronicity, rather than a cause-and-effect, that makes such phenomenon of preternatural gestalt possible as shown by the empirical evidence of comparing and collating ‘above’ with ‘below’, in the long term. Here even the author’s name lends itself to the annealing of harmony by dint of three mothers’ deliberately synchronised pregnancies (in strange and telling contrast to the aged women’s pregnancies in the Wehunt, a search for the gestalt of ourselves?), and the fruits of such synchronicity are the patterns of three, the beautiful baby girl triplets growing up as dealt with by the three mothers and the three Slavic nannies whom the mothers naïvely employed, dealt with by nurture as well as nature, choice of girlish clothing as well as the embedding of intrinsic selves. A harmony, literally made here by musical instruments as well as souls. An intermissory coda to the book’s symphony, I guess. Captivating and deliciously ungraspable. With a dark internal diminuendo coda to its own music, as if such music is caught in a version of Zeno’s Paradox, too.

“They stayed perfect, perfect,…”

“…a knot inside a knot.”

“I lower the binoculars…”

But what binoculars?

It as if this matter-of-fact exercise in a coda-making for any book it happens to end is also a worm ouroboros of spying not only on others but also on oneself, surveillance by sound and sight, amid the humdrum dysfunctional nature of city rental properties as well as the personal relationships that share those spaces. The yearning for one’s own children even before they have become the foundlings of books no longer read, like this one, that isn’t be put on the shelf, or left behind like forgotten hangers.

An insidious anti-story with echoes of deadpan existential authors you also once read. Robbe-Grillet or Beckett or Aldiss’ Report on Probability A?

Or a different Nicholas Royle?

Meanwhile, this book will be read and read again, spoken about and lent out, extending its own disarmingly metamorphosing ouroboros of itself. A significant Weird Fiction book that is the best and longest kept secret, till it is finally out. But never completely divulged. It needs to harbour its own existence for others to discover. And reviews like this one are only ever half the battle. After me comes the flood.

It is the sort of book endlessly to be re-read by one reader as well as by many, and I don’t say that lightly.

end