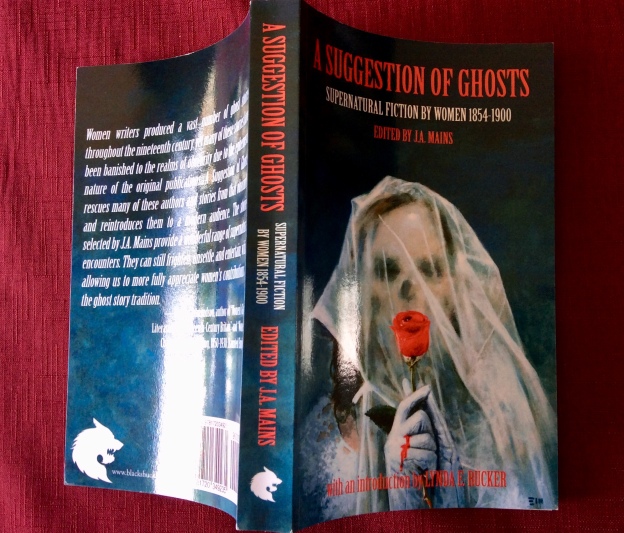

A Suggestion of Ghosts – Supernatural Fiction by Women 1854-1900

Edited by J.A. Mains in 2017

BLACK SHUCK BOOKS

Introduction by Lynda E. Rucker

Stories by Susanna Moodie, Frances Power Cobbe, Georgiana S. Hull, Phoebe Pember, Clara Merwin, E.A. Henty, Manda L. Crocker, Ada Maria Jocelyn, Annie Trumbull Slosson, Lady Gwendolen Gascoyne-Cecil, Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman, Katharine Tynan, Mrs Hattie H. Howard, Elizabeth Gilbert Cunningham-Terry, Annie Armitt.

My previous reviews of older or classic books HERE.

Whenever I read this book, my thoughts will appear in the comment stream below…

My previous reviews of Johnny Mains HERE.

I love the old aunt here who tells this story (via the Moodie one) of a bully of a man in the Kendal area, a series of events and a legend, come together, and I sense there is indeed a veritable ghost only temporarily masked by the bully, a bully who gets his come-uppance on the lonely haunted road to Windermere as come-upped by a yeoman, a word not unlike woman, I guess. But back to the old aunt herself, I say, one who gives great promise to this book here at its outset, a woman whose “elastic mind seemed to bid defiance to decay” and who spoke “her ghost stories and traditionary lore, her legends of the wild wonderful, her long catalogue of extraordinary dreams and mysterious warnings…”

The wild wonderful versus the shooting of ghosts.

“But what did I mean by ‘real’?”

There is to be something uncanny in itself reading these stories. This one in particular evokes my quandary as to whether some of its raw or rough edges are due to its original printing or more modern typos. But, equally, this very quandary adds to my feeling of uncanniness, breaking new ground in these old works being read and opened to daylight after years of their mouldering or morphing in old cupboards of previous generations. This one is genuinely frightening, leaving a taste in the mouth that there is some moral code of ghostly suggestion — arising from this morphing past when it was written — that such night frights and haunting noises and strident chatter around the buhl-table and its mirror simply need to be borne like a hairshirt of horror for the story’s heroine Florence to be able to go to Florence and to remove the dire poverty of familial inheritance from her eventual destiny and from that of her Sapphically caressing sororal sibling called Adela.

“It was wonderfully painted in negative colour.”

This further suggestive story tells of the wonderful innocence of two more mutually affectionate girls (once school friends) who have reunion (one of the girls a visitor to the other) in an atmospheric Scottish mansion, with a tower nearby, a tower belatedly spotted from one of the windows, significant in the hostess girl’s family backstory and her brother with whom the other girl falls in love. There is much Gothic ghostliness and many inheritable machinations involved, mouldy rooms, as well as a special room not so mouldy with ornate paintings, a whole dynasty of complex innuendos of past and budding love as well as broken promises. Too complex even to attempt setting out here, but one feels imbued with something fully unthought out, something mixing Viking and Valkyrie, naive, yes, because it is beautiful but inchoate writing, quite disarming and sometimes untightly drawn, with oodles of constructive ungainliness that most modern stories might eschew but which only long lost stories such as this one can truly harbour as a rich teasing fermentation from among the dust of its past and blushes of inspiration, I suggest. A central house as its own character, one that sinks in and out of the same mould or dust, as the story says at one point. And interruptions from a man about business with a pig. Meanwhile, this whole book is not the discovered “receipt-book” itself, but a receipt book nevertheless, I guess. Testing question to any few who think they have grasped this whole plot: The sixteen year old Margie who is picked up and married almost instantaneously to the man who found her, is there a connection with the name of Marjorie who is the narrator of this story? A question that may prove my own relative lack of grip with regard to the hindsight of dark marvels emanating from this work?

“, and between the suffocating sobs came the bewildering beat, beat, beat of the crushed and lacerated heart.”

A provoking story, and not just because of Esther’s view of her servant Candis! The works in this book are essentially of their time, historical documents as well as genuinely spooky with blatant suggestibility, if not suggestiveness. Here, there is a character’s account within a sometimes melodramatic story, often beautifully observed, and the inner account is told with a traditionally acceptable studied-craftsmanship by an ordinary person, here a young woman, Esther, telling a tale from her own experience about the boastily foolhardy accident, leading to the death in the past of her unrequited sweetheart, an accident in the vicinity of where she now sleeps. This inner account is told to a man called Linton with whom she has had a Platonic relationship since childhood. To my mind, he is not worthy of hearing her tale. He tries to rationalise the haunting. Ms Pember may disagree with this assessment of mine, though. But I sense there is a difference between believing in the supernatural and believing in the preternatural. And this story brilliantly, perhaps inadvertently, deals with this dichotomy.

“It was a rambling old place, and of course it had a ghost.”

An oriel chamber with an eerie tapestry. Straight into the frisson without even a flinch of narrative foreplay, as it were. More girl on girl naive affection leads to her visit and then another visit, when they only had room for the narrative visitor in the Tapestry Room as Ghost Room. She herself calls it a strange story at the end. But it is not just strange, it also has a constructive element of modern absurdity. There is no possible motive (as the narrator herself admits) why the man with black locks and one white lock of hair left the diamonds untouched when escaping from between tapestry and wall and then trying to batter himself back in. A frisson that is more than just simply inexplicable hit me.

by E.A. Henty, aka Mrs Edward Starkey

“‘Our best plan is to keep dark,’…”

This seems most of the way a delightful Restoration Comedy modernised for Victorian readers, a concupiscent haunting by a real and beautiful girl rather than a ghostly haunting, a series of flirtatious manoeuvres and misunderstandings in a large house with its one legended Ghost Room to match the previous story’s, amid a grouse shoot, and a pair of pals with a war’s backstory. Yet, I sense myself haunted nevertheless by some quaint sense of lurking aberration, that rolling bottle across the floor, the Rajah Doodlepooh, corpse exhalation of blood gases and someone else’s later regaling of his epigastrium, the rats in the walls, the feather bed syndrome, a brown-eyed syren, the swearing parrot, flirting wrens, “sugar yourself and I’ll cream you”, “as far apart as the zones”, and that baby moonbeam as inquisitive fairy. A veritable gem. Requited love and at least a personal ghost’s suggestion. A work that contains the word “suggests”.

“Well, will you take charge of my horse if I take a stroll into ghostdom?”

That should be ever quoted as an oblique catchphrase for spookiness-investigating daredevils! Indeed, not into one’s own ‘ghostdom’ but the realm of perceived ghosts outside oneself as proof of their existence. I am not sure if there is proof here, in this traditional means of a story told within a story as an old version of pubtalk, but indeed this is a story within a story within a relatively short source story as a whole! Worth experiencing this work as a quaint rarity, but it is also enticingly deadpan and disarming about an invalid man and his sweetheart thrown from her horse. And the way they now haunt a road for spook-loving daredevils. One conundrum, why draw special “strange attentiveness” to the horse’s “hind feet”? The “half” not portrayed in the story?

“There was a grandeur of terror about the whole adventure not to be put into words; to be understood it would have to be experienced.”

On second thoughts, this is the perfect last line for someone to say on their deathbed!

I think I shall one day take a leaf from its book.

by Mrs Robert Jocelyn, aka Ada Maria Jocelyn

“, so I bustled energetically about the room, heaped coals upon the fire, which, had the season had its due, out to have been conspicuous by its absence, and began to undress.”

The archetype Ghost Room again, in short order, with little narrative foreplay (other than a most remarkable bed with ominous carvings and an unlockable door to some secret stairs discovered by the female narrator as the room’s tenant for the night) but this time the archetype story is spiced by the most under-stated or over-suggested last sentence to end any Gothic Terror! Meanwhile, the means to ward off a haunting by a real or disguised ghost, is asking her beautiful sister (I think) to share the bed.

Sorry, but I find it unbearable to read a story written in elided dialogue. My failing and my potential loss.

I – III

“Does our peace of mind depend only upon death coming early enough to hide from us the truth?”

The first third of this novelette, certainly evokes many emotions. The narrator Evie in another house where this book’s Ghost Room exists and where she is placed because of a full house of guests, again! Her cousin’s wife Lucy and easy gossip where someone thinks the sole womanly role is one of conversation accompaniment! Yes, that, the lightsome. But here increasingly the darksome, where I sense, perhaps without evidence, that a ghost’s suggestion may become more an ingestion, a gestating as gestalting? The cabinet itself is not awful to see, but why not break it open to break its curse, I am not the only one to wonder. The house’s curse as well as the family’s. And then there is that ruined tower where the cousins once played with Evie in childhood. The two remaining male cousins (the third is exiled from this country, I infer), one, George, married to Lucy and with children, the other, Alan, still single, but I sense an ancient form of anti-natalism in Alan’s soul, and both of these men now having donned the garb of maturity with a surly darksome aura, I sense. Even Evie herself has this aura to some extent, her début having been blighted by ill health, it is hinted. In all, so far, this is a tantalisingly textured narration, one that has the seeds of greatness, to which I feel this book has been taking me, getting me ready as reader of it. “…to work me one pair of carpet-slippers per annum,…”

A glimpse of social joy, though, at the end of this first shadowy third. Just a glimpse.

“‘I don’t know; it was just something to say,’ I answered plaintively.”

A self-realisation by Evie in using the word ‘plaintively’ about herself in this narration, especially in view of what she says earlier about “; and above, beyond, and through all things, chattering.” I found this very moving. And makes her later religiously eschatological conversations with Alan even more moving as a historical document of the times and of the times’ underlying angst of credo. Is Evie called Evie for a reason? Meanwhile, we have Gothic frissons in the nights she spends sleeping in the Cabinet room, “dream memories” as well as sounds of a wind outside that disturbs nobody else in the house. And a highly charged vision that I will not describe here for fear of spoiling it, but is it significant in the light of this story’s intense undercurrents? Almost off-the-wall vision in its nature, but also important in perhaps being the only document that actually records such thoughts that happened to beset many people in those days (and still do, today?), thoughts otherwise kept in denial or simply untold except in outlying corners of literature such as this work? Also raw concepts here of man as the devil and today’s “me, too” movement, anti-natalism tendencies and being in charge of one’s own body awakenings??

“‘Luckily,’ he said, ‘there are other things to do in life besides being happy.’”

A huge wisdom, that. Especially in the context of the story of a curse that runs, a curse sometimes halted, but will run again, the human story as a whole. All part of the stoicism and synergy between the genders. Evil and good. Her, too. Him, too. Evil man and good man, alike. Delia and Evie alike, too. Indeed, this story (part of which now explains the exile of the third brother) and our love for such stories of darkness and passion represent an emblem of such an ambiguity of life, and the catharsis here ignited by a ‘maid’ (not housemaid, but spiritual maiden, now her spiritual hymen in the metaphorical shape of the eponymous cabinet was gashed from within and potentially healed) — to give birth, beyond the reach of any anti-natalism, and to annul nullity itself. Just as this book officially denemonises (sic) the Anon of this major work’s author. Gives birth to her name (a process I once used with Nemonymous.) You can forgive, meanwhile, the longueurs of infodump towards the end because of the work’s gestalt, one that includes genuine horror frissons in the middle sections that attracted readers like us to it in the first place with the help of this book’s editor. Indeed, perhaps, readers like us together create, and are created by, the hard-won synergy that this work instils. A Road to Damascus, and it is not accidental that this work explicitly featured St. Paul. And Alan and Evie, Adam and Eve, as an assonance of our originators, originators in a new Eden beyond – or accepting of – the grasp of God or Satan. Cain and Abel, Jack and Alan, too, as ironic brotherly ‘love’? One can continue this suggestion of extrapolations further, no doubt.

“Generation after generation, men or women, guilty or innocent, through the action of their own will or in spite of it,…”

“Sometimes it was hard for Letitia to realize that she was not another little girl.”

An engaging Alice-like, Narnia-like, CLOSED CABINET-like tale of Letitia and the forbidden-to-be-opened green door, but to what place would it open? We find out, in this unidle-instructional, homely, crocheted sampler of a fable: and it is interesting to cohere the lessons on “predestination” not only to Letitia but also as filtered by the gestalt present, future and past, that of Alice, the Narnia children and, of course, this book’s own Evie. There was, however, little opportunity for “girlish confidences”, although with other little girls she mixed. But there was a “stent in a story-book”, “a well sweep” … and those Injuns and catamounts … “They come most every night.”

“, for who else would harden the human heart to desecrate a new grave, and to cut from the helpless dead the strip of skin unbroken from head to heel which is the death-spancel?”

An extraordinary and prophetic short wave of a story published in 1896, a powerfully oblique emblem for a transcendence/ forward-punishment of the easy grabbing Harvey Weinstein syndrome.

“, and still that ghastly object was stealing nearer, nearer.”

A short short reminding me of when I gazed into old haunted houses on Walton-on-the-Naze Pier during the early 1950s when I lived there as a gullible child. Just for the price of an old penny. Now I’m looking back, as in its last paragraph…

Brilliant title, too. Wouldn’t let me let me go?

by Elizabeth Gibert Cunningham-Terry

“By the way, you don’t know what a funny sensation it is to have a ghost pat your face, Miss James.”

Miss James is working as an accountant in Mexico in an old building where there had once been a lethal duel. She makes fun of the cashier who tells her his tale of the ghost, until, working late (with significant assiduity of arithmetic) to reconcile a few odd dollars in the balance sheets, she is herself physically caressed by the ghost and led to one trove that she takes amorally, as she thinks. An engagingly humorous tale of creepy and unvirtue-signalling strength, with a neat ending. In fact the ending could be altered by its republication here!? And, now my publicly reviewing it!

“Really I don’t know that it is quite the proper thing, is it? —to have clandestine meetings with a ghost.”

A mixture of letters from Connie “to an intimate friend” and of someone else’s pure narration, about her cousin Nellie, Nellie’s dreams or visitations in this book’s Ghost Room, meeting the ghost of her supposed drowned-at-sea beau Randolph, a beau exiled by her Uncle as he disapproved of the match. Almost a SF story with a contraption involved that is not SF at all but a premature invention centred on a phonograph clock (hope that is not a spoiler.) Basically a story that is a satire on Tibetan theosophy and other esotericisms. Engaging enough, but a strangely throwaway work as this book’s editorially intended climax, making me glad that I now have fabricated the prospect of a different climax to my reading of this book….

“Don’t you want to hear me speak my piece?”

And I am so very grateful that I was persuaded to hear this piece spoken by itself, coming into my life, as it were, not as a he or she, but as a transcendental ‘it’, as the narrator herself learns to call the boy. Another prophecy (here in 1890) for our fluid times that often seem unpredictably repressed and liberal, by turns… It is a major work, no question, and once you get used to the woman narrator’s elided speech rhythms, it flows steadily through to your soul from her soul, about her own backstory, the loss of her three boys by drowning (brothers she seems to have mothered) and then her teaching in a boys school, and here in this narration looking after a house in New York, where she is struck that it is lonely inside where she lives but lively and busy outside in contrast to the vice versa whence she came. Then, through her words, we experience the recurring visitation by the ‘boy’ ghost to this lonely house, an experience of her listening as if he speaks or as if she speaks for him, him or her, or a single ‘it’ of rhapsody or rapture, a relearning (‘learn’ used colloquially by the naive narrator in this text as meaning ‘teach’), a deployment of the Christian religion by her catechising the ghost, up to the point in time when it is Christmas…. There are some remarkable passages in mammoth monologue (cf James Joyce’s Molly’s Monologue here used for Christian purposes rather than a woman’s sex life), a work that I am astounded has not been discovered before. It is seriously powerful and constructively ambivalent beneath its religious certainties. This is a ghost story where the ghost truly exists, beyond any ghost story I have ever read, as a sort of gestalt of naive haunter and naive haunted. Naive, but essentially full of wisdom by being cast from speaking its piece from piece to piece, time and time again, pieces of the eventual absolute or whole. I cannot do full justice to it here. Needs to be read by any serious lover of ghost stories, and of literature in general, I think.

This book as a whole is quite a discovery, in spite of some minor typos (transferred or new). Speaking to us down the ages, evoking past ghosts into their future-that-is-us so as to impart oblique lessons of frisson, fear and, often, fickle timelessness and fun. I sense things beyond the text, while thinking outside and inside the box or closed cabinet, things that have been maturing within some fermenting darkness of suggestion, suggestiveness or suggestibility, till suddenly these things are re-invoked and now aching for a revelatory fusion or, even, a preternatural re-interpretation of their confusion!

end