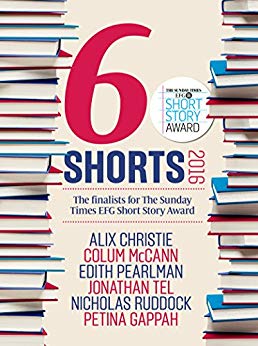

6 Shorts 2016

The Dacha by Alix Christie The News of Her Death by Petina Gappah What Time Is It Now, Where You Are? by Colum McCann Unbeschert by Edith Pearlman The Phosphorescence by Nicholas Ruddock The Human Phonograph by Jonathan Tel

The Finalists For the 2016 Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award

When I read this book, my thoughts will appear in the comment stream below…

“Even a decade after the fall of the Wall, most of the east was still the shit-brown color of old stucco.”

A mainstream, eventually downstream, story of an American woman and her German husband — whom she met back in America and now with two small kids — buying a dacha in what was once East Germany. I sense this is an adeptly conjured genius loci, including the later surprise that the lake is a site for nudist bathing and the mosquitos fat. And the German woman, a Yankeephile, still living nearby with a small son, who sold the dacha to them, turns out to be conniving in different respects for her own benefit. A believably characterised template for humanity where deviousness mixes with naked openness. Quince jelly and penis rings. A symbol for our times of fake news and naivety, where Walls have again become the answer to everything? Or Dachau?

‘What about you Shylet? A smoking girl like you needs something to make you even more smoking. How about some smoked fish for a chimoko?’

A characterful womanly gossip (if that is not being sexist to say) between hairdressers and customers in an African hairdresser’s possibly near Lake Kariba, salon or saloon depending on one’s view of the establishment’s class, a customer promised special braids, about to fly back home to ‘Men Chester’ via Amsterdam and London, learns that the hairdresser called Kindness who promised the braids has died, not of HIV, but of being shot by her boy friend…. A fish sales man vists … an older woman comes in, Pentecostal or Roman Catholic, and there is a teenage girl with half done braids who sweeps up. No need to sweep up after this breezy, dark-brightened story, though. It is a slice of life, a backdrop to the variegated human condition in our difficult times, the remainder of our story yet to be braided. And I will now reread Anita Brookner’s At the Hairdresser’s as an ornamental foil. Hers was a death, too. One of my favourite writers.

What Time Is It Now, Where You Are? by Colum McCann

“All the beginnings he attempted — scribbled down in notebooks — wrote themselves into the dark.”

“…and she could be facing the gothic dark of the Kerengal Valley,…”

The perfect story for the perfect gestalt real-time review, at last! A story where we follow in real-time the writer of it, either the freehold author himself, or that author’s leasehold one who sits within the perfect mathematical triangulation redux? A haunting story in itself, as one of them tells of writing about Sandi, an American woman marine in Afghanistan, on solitary voluntary sentry duty in the dark landscape as the other off-duty marines celebrate their Afghanistan version of midnight on New Year’s Eve. She readies herself to call on satellite phone her maturing 15 year old son in, say, Charlestone, back home. And also to speak durng this same call to her lover, the co-mother of that son they share together. Twice, New Year Eve is pluralised to New Year Eves in this working text.

“…since this is what our New Year’s Eves are about, our connections, our bonds,…”

Any questions?

“Those mannequins, they replace their own heads at midnight, they rifle the safe, they choose the finest jewelry, they go dancing.”

The eponymously lightsome version of Pride and Prejudice, a family with a large number of daughters, and the politics of love, sex and marriage, but here this New York Jewish family is taken beyond Austen’s end, towards death, but always a “lucky destiny”? It is a different social world altogether. Full of lightsome words and behaviours, backrooms and surreptitious signals, an imputed camel’s serendipity as objective-correlative, despite diabetes, and other slings and arrows of life, some without limbs or straight backs. Garments and bespoke colours. Humanity as a humour, in both senses of that word.

“…not bothering with further romance he possessed her on their plush couch leaving a stain that would never fade, which they called “Brenda” after their one dear child, the result of that incident.”

“You didn’t always need words.”

“Memorizing was preferable to understanding.”

The wonderful description of the family’s telephone device — dating this extended novel period in the short form of a story — dials your digits up literally towards chirpily saluting this work’s satisfying stoicism.

“Then came ‘the harness, please’, of which there were also two, taken from a worn valise in the corner, ‘wear it thusly, like so, around the waist, yes, and cinch it up, excuse me, here, between the legs, good, that’s good, there’, while the strongmen finished up, one of them clapping his hands in satisfaction as the interior cable now hung slack through the portal though much of its length still remained in the room,…”

From Sandi’s earlier catharsis in Afghanistan and Pearlman’s lightsomeness — A dream of Nice or a literary effulgence as if Proust were creating magic realism, a sacrifice of two girls found on the beach to replace others to become phosphoresciennes, the ultimate Hawling between Côte d’Azur and Africa, a geomancy beyond carnival, beyond beyond the countryside around Nice. The Hawling created by all my Gestalt Real-Time Reviewing over the last ten years, as if written specifically for me. But I sense every reader may feel this, too. Written specifically for each of them. An occult ritual within a rite of passage as if written by Damian Murphy (now brocaded by its own inner phosphorescence), but then sadly rounded off by a Gide-like Peste (Camus, rather) that is our world today. The girls become groped (as well as hawled) as a me two, too. Making this an ironic self-sacrifice for the sake of being able to experience such a Proustianly ornate (yet deadpan), compellingly narrative-driven story in the first place. No mean feat. Mean, too.

“We understand them in order to defeat them.”

And so we do, by dint of each ending of this story being different each time you read it. It’s as if you have never read it before. As this Chinese woman, in the Armstrong contemporary moonwalk period, goes, as librarian and wife of one of the scientists already there, to a part of the post Mao-Stalin handshake China where the Mad Scientist bomb is needed secretly to be part of this and other experiments. She has sex with her estranged husband as if it is illicit. A go-between is the eponymous songster… and we love the way we are beguiled by the permutations of love and impregnating, as humanity once impregnated the moon. All part of a mighty deadpan Hawling of a spirit, I sense, with added bespoke ironies for each reading you make… all grooved as mnemonic.

“they restored the original crack in the roof through which rain dripped, and included a stuffed rat on the floor”

“a vast deep pit with many yellow-hatted workers swarming in and about it — where the foundations are to be established for the tallest of towers, that shall one day be built.”

And her sex with the estranger is a hawled geomancy cultured with that in the previous story’s Phosphorescence, where landmarks and terrains are part of such love, now potentially, I feel, stretched from earth outward, beyond the moon to the stars…