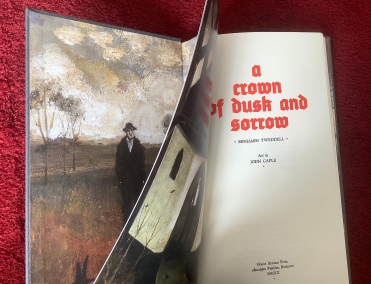

A Crown of Dusk and Sorrow – Benjamin Tweddell

Mount Abraxas Press MMXX

My previous reviews of Benjamin Tweddell: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/tag/benjamin-tweddell/ and of Mount Abraxas Press: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/complete-list-of-zagava-ex-occidente-press-books/

When I read this book, my thoughts will appear in the comment stream below…

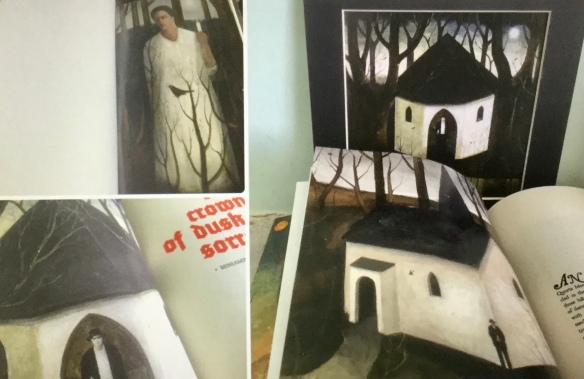

Paintings by John Caple

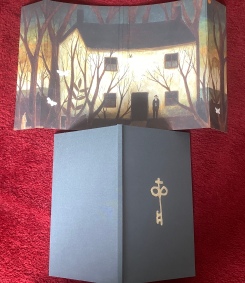

The well-accustomed and incomparable Mount Abraxas luxury of book design, with just over 50 pages.

Pages 7-10

“Pulling up his collar against the evening cold, he glanced back to the wooded ridge of the Blackdowns, and brooded,…”

I pensively follow the thoughts of Daniel, thoughts reported to us by the prose of narration, but whose narration is it, a storyteller or this book itself that contains the storyteller’s words? The felt nature of this book seems to impel one to ask that question, a sort of question readers don’t normally ask themselves when reading ordinary books. So far, this has the down-beat of the “eight fruitless years” from when he first came to this part of secluded Somerset, and I feel the sap of further narration underfoot, an autumnal sap, if there is such a thing, when I hear about his wife Helen, now dead from just before he came here with some of her belongings and books, setting up a poorly paying bookshop in Wellington… I gather it is around 1930, so this book gives off that sense of aging, too. Can a book — with freshly cracking pages as I turn them, with still untouched texts and artworks, and with a brand new gold marker ribbon — have somehow already otherwise aged? Another question I have never asked myself before.

“Such simple, jovial companionship felt to him, at this moment, as unobtainable as that distant star.”

Pages 10-17

“The Leland had belonged to Helen.”

That word assonance needs to be noticed, I guess, and other than in a book, like this, that focuses the susceptible reading eye further and further within the text towards hidden meanings, that might have been missed. But, equally, the mind, as well as the reading eye it employs, needs to be susceptible. Meanwhile, Daniel, still in love with his bookshop, despite his lack of business impetus in making it pay, receives a visit from a man called Jacob who wants to consult a Leland book about Wulfric of Culmhead rather than pay for it. A mercenary attitude, that is soon transcended, as they both together dig deeper in the local legends and history…where ancestral burial places are where the body’s spirit stays, rather than from where it vanishes elsewhere. Evoking, for me, at least a tenuous kinship of belief with this book itself…? A potential vigil of inversely out-reading it? By a holism still so new, shall its inner putrefaction be made holy?

Pages 17-25

“Lepers, of course, paradoxically, held a unique position. […] …thus touched with a strange holiness.”

Lepers, as representatives of today’s Covid? Leapers, too, I suggest, as I happen to be trying to substantiate forms of leaping in both my reviews — one review erstwhile, the other concurrent here — of the Big Books of Classic and Modern Fantasy, if fantasy they indeed be. For example, upon their combined countryside trip by car and then by foot, seeking Wulfric legends or truths, the much older Jacob explicitly ‘leapt across a series of boulders’, and later the word ‘interloper’ is used for Daniel’s own unsettling feeling of self.

The trip’s car journey, beautifully cinematic and almost light-hearted through these Somerset places, until a more palpable atmosphere ensues as they walk, a sense of fear, their talk of a hamlet that once did not have a sudden exodus but a piecemeal drifting away because of some subtle hidden threat. We absorb, alongside them, glades and trees: scenes well-couched in an old-fashioned fantasy style of literature, but eventually soporific and textured with undercurrents of what lies even deeper amid the mulch of our imagination, if imagination is the right word. Both men appear to doze off and they dream concurrently, what I would call a co-vivid dream indeed! A dream leaping between them, in contrast to the soporific? Awakening, it seems, with the ‘taste’ of a stranger’s words on the tongue if not an exact memory of them. Did the stranger talk about different things to each of them simultaneously, or talk to them separately about the same things?

From Internet: ‘The “-loper” part of “interloper” is related to Middle Dutch and Old English words meaning “to run” and “to leap.” An “interloper” is essentially one who jumps into the midst of things without an invitation to do so.’

Pages 25-37

“How simple it seemed, and how meaningless too, this dance, of commerce and of culture — a mindless dance even a child could perform. Every pattern, every step he saw, yet all were bereft of grace, or meaning.”

In spite or because of the audit trail of Daniel’s various dark epiphanies so far being unclear to me, I continue to relish the disarmingly old-fashioned and poetically textured and endemically old-weird-genre-spirited style that the story’s told in. His temptation to leapfrog commercial probity to get a valuable book, his attendance of a party in a large house where he is spurned for the gravestone-hugging rumours about him (one woman there resembling his late wife Helen), “horribly vivid dreams”, the parallel downbeat post-Great War era at the turn of the year into 1930 with Germany’s book-burning and Daniel’s own sentiments adumbrated here, Daniel’s as well lunacy’s “prowling”, ‘foxes crouching’, but when, stirred, Daniel manages ‘to leap a stile’ and then “leaping two steps at a time.” But also this still gestalt-morphing, audit-trail-of-words-defying, downward-spiralling, potential-leaping-or-leprous quote… “Ere long I bore fruit and throve full well. I grew and waxed in wisdom. Word followed words, I found me words, deed followed deed,…” (King Hákonar’s Saga, blending into Lammas rituals, Poe’s Raven, Book of Isaiah and this book’s own momentous title itself…) and you need to touch-and-read this book-with-such-a-title to experience the full quote.

Pages 37-51

“If his home was a prison, then it was an incarceration that he welcomed. […] …the secret language of his dreams oozed into the waking world. […] A vast conflagration lay ahead,…”

The impending War, and Daniel’s own significant change of inherited fortune or blight, still with his melancholy mindcast in death’s nowhere and nevermore — and a richly wordy folkhorror’s epiphany of prowling if not sprawling prose — form this lengthy coda to the book, sequential to the quote that I unfinished in my previous entry above. But from that quote emerges a significant raven that he follows in the sky…not leaping, but now flying? But we need to sift through this coda’s scenes, all the characters so significant to him in recent years, “all a part of him”…a gestalt…and I am left ever-tantalised yet moved. Leaving me “just a ragged, lonely, forgotten old man.” Here, on 1 September, at the “waning of midsummer”, or Midsommar. The jump unleaped. Leaving me, too, with old Gods ‘ravening’ “for the sanguinary propitiation to come.” Shrieks of horror or a rapture, which is it? A monolith, a dead monument to once ancient hope, now being unetched by modernity? ‘Fallen logs, leprous’, I still climb ridges, even as that old man. The taste of diffused gold, as I ready myself to speak to the dead, for their wisdom. “No lepers were these, but outcasts of another kind.” This work also has a momentary sparrow between winters? Between writers, a co-vividness. In my banquet hall, and in my lockdown, too. Suspended between life and death, it says somewhere in this coda. This physical book and its design intrinsic to the prose. And vice versa. Do not judge them otherwise.

“This waking life is but a shadow, my friend, a dream we share.”

END

I forget if I have mentioned it above, but the figure within this doorway is a spitting image of myself when I was younger. Others who know me have corroborated this thought.