My huge Bowen story review (5)

As continued from the fourth part of this review of all Elizabeth Bowen’s stories here: https://nemonymousnight.wordpress.com/849-2/

My reviews of EB stories so far, in alphabetical order: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/31260-2/#comment-23256

My previous reviews of general older, classic books: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/reviews-of-older-books/ — particularly the multi-reviews of William Trevor, Robert Aickman, Katherine Mansfield and Vladimir Nabokov.

“She never had had illusions: the illusion was all.” — EB in Green Holly

SEE BELOW FOR MY ONGOING REVIEWS OF BOWEN’S STORIES

A WALK IN THE WOODS

“Willing or unwilling they walked in circles, coming back again and again to make certain they had not lost their cars –“

“Yes, mist that had been the natural breath of the woods was thickening to fog, as though the not-distant city had sent out an infection.”

“Against the photographer’s shoulder-blade eternalized minutes were being carried away.”

“And still water in woods, in any part of the world, continues an everlasting terrible fairy tale, in which you are always lost, in which giants oppress. Now the people had gone, the lovers saw that this place was what they had been looking for all today. But they were so tired, each stood in an isolated dream.

‘What is that floating?’ she said.”

Pure Bowen, also harnessed by — or harnessing — the now perceived blend of Aickman’s two separate and otherwise quite distinct stories, WOOD and INTO THE WOOD*, that cuckoo clock routine of the INHERITED CLOCK’s captured or hurtful ‘minutes’ as real things going in the same circles of time, and a woman’s lot in life and her need to be absorbed into what? A relationship with a man, whatever the cost or lack of dignity? Or what I call Null Immortalis as a way toward death? Here the relationship with another man, surreptitiously in a wood, instead of her husband. She is ten years older than the new man with whom she goes into these woods on the city’s margins, where tranches of other people’s lives — either watched by two fifteen year old girls as she and the man kiss and watching, themselves, in turn, a photographer photographing another young girl across a lake.

Thermos Flask as treasure, keeping warm the life that longs to go cold? And all the women who are left in cars like glassed specimens (or even statues) in the midst of the wood, awaiting their man to come back. They may have to get home by Green Line, if they can’t drive, I guess.

“As he saw the girls’ pink faces stuck open with laughter he saw why Carlotta hated her life. He saw why she towered like a statue out of place. She was like something wrecked and cast up on the wrong shore.”

“Carlotta smiled, but she felt her throat tighten. She saw Henry’s life curve off from hers, like one railway line from another, curve off to an utterly different and far-off destination. When she trusted herself to speak, she said as gently as possible: ‘We’ll have to be starting back soon. You know it’s some way. The bus —’ ‘No, we won’t miss that,’ said Henry, rattling the flask and smiling.”

“All day the woods had worn an heroic dying smile; now they were left alone to face death.”

………

Reading the set printed paragraphs in various different orders potentially gives us a different hidden story. We are observers in that wood, too, interpreting its paths differently, each of us with our own tranche of endless existence. Yearning for some gestalt. Or peaceful nirvana.

“This girl over the water in the fog-smudged woods was to be called ‘Autumn Evening’.”

================

*from my earlier reviews:

WOOD – a house imitating a cuckoo clock with alternating rain-sensitive puppets that manipulated the metaphorical strings of themselves till the very end. Even their only child spotted inside the house as clock.

INTO THE WOOD – She resists her final communion with the excursion’s maze of pathways and one wonders if she ever shall. At the end she seems prepared to do so. To find that once insufficient answer, “beyond logic, beyond words, above all beyond connection…” A marvellous work, that also involves the Aickmanly nature of gender interaction and marriage and the masculinity that poisons some of us, whether man or woman, with these following eclectic keynotes in this work of time’s own gluey resistance movement and incursions against excursions: “Don’t leave the road […] You’ll sink above your ankles.” —

SONGS MY FATHER SANG ME

“…the walls were rather vaultlike, with no mirrors; on the floor dancers drifted like pairs of vertical fish.”

“‘It’s what they’re playing – this tune.’

‘It’s pre-war,’ he said knowledgeably.

‘It’s last war.’

‘Well, last war’s pre-war.’”

In a dance nightclub during second world wartime, a man and a woman, together, their affair a seeming ‘flop’, with neither of them caring for the other; her mother was once a ‘flapper’… and one tune played reminds her of one of the two songs that her father once repeated and repeated much to her mother’s marital irritation! And this sets the woman off describing her father in a remarkable monologue as filtered by Bowen skills, that freehold stranger emerging in the text of ‘Candles in the Window’. A monologue as part of a dialogue with the man, but essentially a monologue… the mother’s shingled hair and the father’s so-called ‘lordly’ singing as if harking back to hidden mythologies… and her father was aged 26, post the first war, as she speaks this description of him at the outset of her monologue….

“Sometimes his eyes faded in until you could hardly see them; sometimes he seemed to be wearing a blank mask. You really only quite got the plan of his face when it was turned halfway between a light and a shadow – then his eyebrows and eyehollows, the dints just over his nostrils, the cut of his upper lip and the cleft in his chin, and the broken in-and-out outline down from his temple past his cheekbone into his jaw all came out at you, like a message you had to read in a single flash.”

Her early life within her parents’ marital void, and the location of dreary bungalows with satin cushions and curdled materials, and stuck windows, a maze of unmade roads near Staines, some of the neighbouring bungaleers keeping hens! The father becomes a travelling salesmen in vacuum cleaners, ironically trying to avoid other voids by such false purities. And on her 7th birthday he takes her on one of these selling trips. And he struggles to maintain his integrity in face of his daughter being too early for him, and what happens and what is hinted at is as powerful as the void he leaves. But if he is in the night club tonight, he’d be in his fifties, not 26.

“‘No; it wouldn’t work,’ he said. ‘It simply couldn’t be done. You can wait for me if you want. I can’t wait for you.’”

That was her father of whom she speaks, not the man whom she today uses as a sounding-board’s tabula rasa (with that earlier ‘blank mask’?) so as to express and hopefully exorcise what she has wondered about for years. Void to void.

Her childhood birthday’s purple manicure set left along with her in the car where her father, before avoiding what had tempted him as if he believed that she was not really his daughter at all, had been viewing alongside her a vista of England laid out before them in the post-war peace that our soldiers had fought for and won, a peace now vanishing in a new pre-war… vanishing into his own voids as he does, too, leaving her in the car for police to rescue. And, for me, time is thus ever both pre- and post-itself! Like a metaphorical maze of un-made roads.

“I don’t think I discovered for some years later that the principal reason for newspapers is news. My father never looked at them for that reason – just as he always lost interest in any book in which he had lost his place.”

And he had lost his place here, too! Even the book itself is lost like the one that lost its foothold in ‘Foothold’.

“…and the blue of earth ran into the blue of sky.”

“…khaki melted into the khaki gloom.”

COMING HOME

“Life’s nothing but waiting for awfulness to happen and trying to think about something else.”

As I read this, the passion of the reading moment made me think this was the most exquisite example ever written of quite a long but still short-short story, and it still is, as I write this about it. An apotheosis of Katherine Mansfield. And Bowen distilled. Even the slightly miskeyed ‘brown’ in brown hat, as opposed to blue hat, autocorrected at first to ‘Bowen’ on this my thus tutored computer. ‘Grey gloves’ and ‘primroses’ were keyed correctly in the first place. Rosalind is 12 and anxious, thinking doubts about grownups’ false assurances about life, but her Darlingest mother is her ultimate bolster; she comes home from school excited that her essay was praised so highly and needs to share this with her mother —

viz. “She had understood some time ago that nothing became real for her until she had had time to live it over again. An actual occurrence was nothing but the blankness of a shock, then the knowledge that something had happened; afterwards one could creep back and look into one’s mind and find new things in it, clear and solid. It was like waiting outside the hen-house till the hen came off the nest and then going in to look for the egg. She would not touch this egg until she was with Darlingest, then they would go and look for it together. Suddenly and vividly this afternoon would be real for her. ‘I won’t think about it yet,’ she said, ‘for fear I’d spoil it.’”

[Like a reviewer spoiling a plot?]

And: “…it was the supreme moment that all these years they had been approaching, of which those dim, improbable future years would be spent in retrospect.”

— but Darlingest is unexpectedly not at home! Imagine that! What wretched wrenches of a child’s spirit. She loves her mother even more than Marcel loved his mother, and here there are ‘forgotten macaroons’ in contrast to the future promise of a ‘petit madeleine’, I guess! But one hopes Rosalind will survive just as long in order to look back and know that grownups are vulnerable, too, in a rush of memory. We can only hope because this story is too short to tell us.

It does, however, have reference to an ‘infinity of time’ – the real-time and lasting passion of the moment and the forever of hindsight – like when she was told about her essay —

“For an infinity of time the room had held nothing but the rising and falling of Miss Wilfred’s beautiful voice doing the service of Rosalind’s brain. When the voice dropped to silence and the room was once more unbearably crowded, Rosalind had looked at the clock and seen that her essay had taken four and a half minutes to read. She found that her mouth was dry and her eyes ached from staring at a small fixed spot in the heart of whirling circles,…”

And there are the ticking of clocks, and then more clocks, inherited for some future hindsight or retroactivity — when she got home and found Darlingest missing. Her anger at finding her missing was tantamount to killing her mother in a road accident. That frozen moment of panic… not of passion —

“She heard herself making a high, whining noise at the back of her throat, like a puppy, felt her swollen face distorted by another paroxysm.”

But:

“Nothing had been for the last time, after all.”

The complexities of such a story of this size is like Zeno’s Paradox now become a moment apotheosised into an infinity of autocorrected hindsights. A plot spoilt, one where the passion of the reading moment is wearing off? Not yet, and I have spent some time this afternoon already writing this review of it.

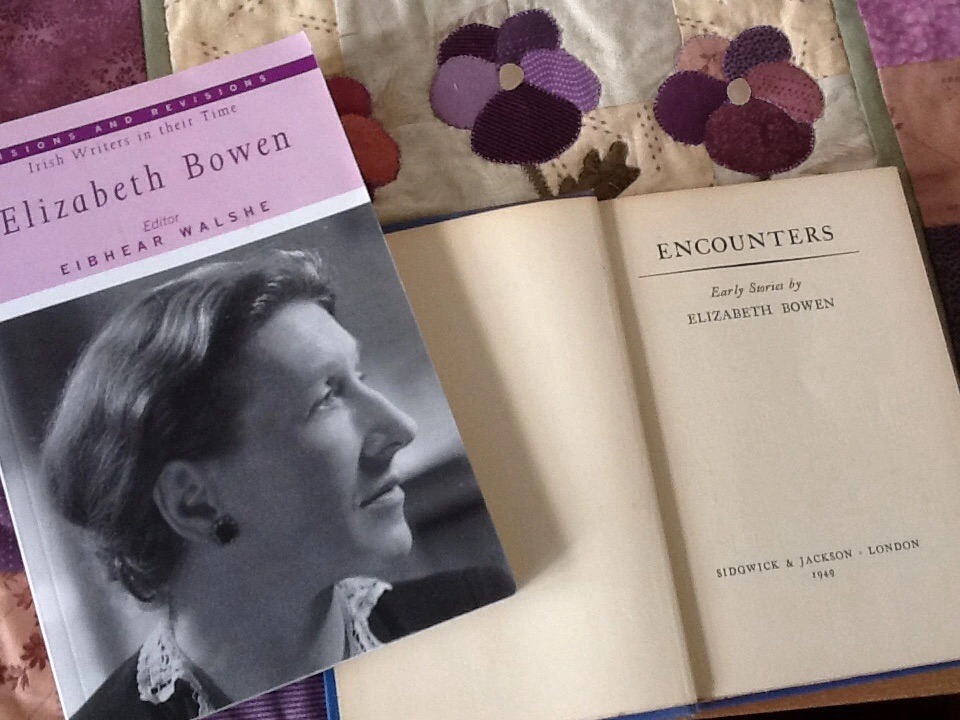

I have now looked up the previous review I made of this story here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2014/12/16/encounters-early-stories-by-elizabeth-bowen/ and this what I said about it in 2014…

Coming Home

“An actual occurrence was nothing but the blankness of a shock, then the knowledge that something had happened; afterwards one could creep back and look into one’s mind and find new things in it, clear and solid.”

That seems to be the essence of dreamcatching books…

Rosalind’s Essay that she took back so proudly from its monumentalising at school, took it back home to show her Darlingest Mother, who has gone AWOL… at least temporarily…

“Life’s nothing but waiting for awfulness to happen and trying to think about something else.”

Yet…

“This was the mauve and golden room that Darlingest had come back to, from under the Shadow of Death expecting to find her little daughter…”

So, if that Essay is mother and daughter’s Shadowy Third, then this very Book of Encounters is ours.

“…smiling at the daffodils.”

Coming home.

GHOST STORY

“Holly, no doubt brought in by the butler, was stuck in the Sèvres vases each side of the clock.”

A clock’s tic tac is the only sound to break the silence of the white mist outside this mansion. This is a Bowen classic, even though it might seem unfinished. But to be unfinished is often good, and these two young cousins, Oswald and Verena, meeting for the first time at Christmas, invited by Cousin Meta, who like all good meta- characters fails to materialise. Her Patrick had just been killed when crashing at Brooklands, an accident or by suicidal design? Meta apparently needs to reorder the succession of heirdom in the family, the family that the light upon paint makes their portraits seem protruding faces into the room (“these people seemed to be popping out of their ruddy skins.”) The litany of family members as multiple cousins and the nature of their strange deaths is imparted to us, deadpan and disarming. Will Oswald and Verena ever transcend the house and its servants towards meeting Meta? Will they forge a romantic attachment over the boiled eggs? Not fortune seekers so much as conscripted familial meta-spaces for the future. The whole resonates with the probability of ghosts, including the dead Patrick appearing to Verena. All is steeped with Null Immortalis that arguably unfinished stories can supply. Holly, increasingly in Bowen, seems holy to me. A symbol of gestalt or holism, too? That and ‘candle dreaming.’ With nobody truly buried. Each room too is claustrophobic through the impingement by bric à brac, the only space is the height above such obtrusive, suffocating furniture and things as well as thoughts. Including one telling thought as thought — or even spoken — by Verena after spending the night in the erstwhile Janet’s room… (Janet died of a rat-bite.)

“All Cousin Janet’s moths kept me awake: their wings made such a flutter behind the glass, till I had to get up and take them off their pins.”

“…the glass roof admitted the black night.”

SUMMER NIGHT

A novelette with various viewpoints, a woman driving in her car evocatively driven by words, a summer night, a hotel in a dog racing town, her quest in adultery with a man called Robinson, one of her young daughters, Vivie, back home, who rampages as as hot like an animal in naked skin, another man called Justin with his deaf sister Queenie, and much else that flows over the reader with shifting shapes of half caught characters . All linked with each other.

A night’s moment in Ireland amid an unseen conflict, the Second World War — similar, I find, to people today across the world amid a silent conflict with an invisible enemy, and if you read this work, you will understand what I mean, I hope. Such as people moving between houses and between each other, almost surreptitiously under such an oppression, falling in and out with each other, passions curdled. A skein of characters by journey and telephone in a beautiful but tantalisingly oblique Bowenesque where our instincts of reading through sprawling osmosis are more important than analysis and plot retention, the characters living amid a symphony of different emotions and motives.

Just three of many example passages from this work that best suit my evolving gestalt real-time review of Bowen’s stories so far…

“He had to share with Queenie, as he shared the dolls’ house meals cooked on the oil stove behind her sitting-room screen, the solitary and almost fairylike world created by her deafness.”

“Now and then in the grass his foot knocked a dropped apple – he would sigh, stoop rather stiffly, pick up the apple, examine it with the pad of his thumb for bruises and slip it, tenderly as though it had been an egg, into a baggy pocket of his tweed coat. This was not a good apple year.”

“Vivie who, turning over and over, watched in the sky behind the cross of the window the tingling particles of the white dark, who heard the moth between the two window-sashes, who fancied she heard apples drop in the grass.”

My review today of THE DISINHERITED here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2021/10/25/and-a-chandelier-that-hung-in-a-bag-like-a-cheese/

My review of THE LITTLE GIRL’S ROOM here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2021/10/26/she-was-in-fact-for-herself-a-most-unfriendly-playmate-for-she-was-treacherous/

litTlE GIRl

THE GOOD TIGER

“The tiger was glad Mrs Jones had left. ‘She was too fat,’ he thought, ‘and not a friend.’”

This review continues here: https://howivi.wordpress.com/341-2/