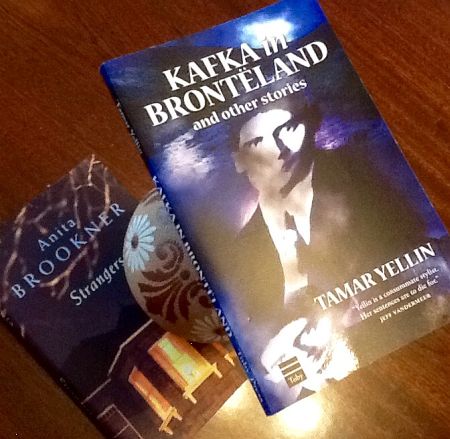

Kafka in Brontëland

11 responses to “Kafka in Brontëland”

- .Reply

-

Moonlight

“He was fifty seven years old and perished of a painless cancer.”

You know, these stories seem to get better and better, but I know in my heart of hearts that they are all equally good as separate entities, it is just that their growing culmination or gestalt gives me that impression of leapfrog by excelling. This story tells of more disorderly accretive objects as a collection as well as multi-‘objective correlatives’ in union, as we follow the path of an artist of ‘minor fame’ within ‘minor frames’ via the insight of another male narrator, one named Norman who reminds me investigatively of myself and my real-time reviews. Not a hearty reminder, but one that imbues me with the ‘beauty of failure’ as this extremely evocative story finally conveys to the reader. The minimalist moonlit paintings, beyond and behind ‘financial disaster’ or Ruskin’s ‘morality of detail’, grow in my head as if they are photographs applied with the story’s textually explicit palimpsest of paint. ‘A cry for meaning.’ -

A New Story for Nada

“There is no point in reading those old stories any more. I could give them to you, but you wouldn’t learn anything about me from them. / Sometimes I think I give people the old stories in order to protect myself, to prevent them from finding out who I really am. Those stories are safe and complete, they are polished and published. They hold not one scrap of danger, nor one glimmer of discovery. They are so old now I have left them so far behind, they live in another life, they breathe in another country.”

You hope that the author and publisher will forgive you for quoting such a long passage from the beginning of this story, but you feel it encapsulates not only this whole book so far and its envisaged author as envisaged (perhaps differently) by you and the author herself but also an earlier preternaturally predictive sense of the nature of this your real-time review itself in 2015. -

A Letter from Josef K.

At first I wondered if this was Mrs Rochester speaking from her perception of Kafkaesque confinement. A confinement by birth towards ‘the rediscovery of death’ (to quote the title of a Mike O’Driscoll story). Sentences to die for.

“I fully anticipated a death sentence.”

This is a remarkable book but – possibly because of that very remarkability – it seems to have been imprisoned in a forgotten library just as the letter-writer is imprisoned in the last story. I hope this review at least helps toward the book’s full release. From the penal colony of self toward a trial by readers, then, by some form of metamorphosis, gaining its due of dizzy heights…

end

and other stories

by Tamar Yellin

The Toby Press (2006)

“Her sentences are to die for.” – Jeff VanderMeer

“The floor was a mass of trampled charts, the walls a campaign; beneath the window with its dead geraniums lay the big atlas strewn with spider trails.”

You won’t believe this story, but you will, I claim, find a higher truth than simple belief.

Right, I’m yelling Yellin at you. No half measures, here; to die for, yes, and maybe that’s how it will turn out. She’s herself plus a cross (excuse the expression) between Anita Brookner, Elizabeth Bowen (Bowen long confessed as my favourite writer ever) and an interstitial Rhys Hughes and something Jewishly indefinable, and I am not the right person to define it. This story is constructed upon a family in our ordinary world as a classical set of characters like Odysseus and Penelope, but mundanely entrammelled by endlessly contrived goals where the contrivances are more important than the goals, a mum’s flirtations, her dad’s mixed up maps of littered routes as well as emotions, as the imputed child narrator poignantly characterises him as erecting a craft for travel, a roundabout Magic Realism that we readers fear will never work towards any culmination that the story’s title portends. Utterly unforgettable. And I haven’t.

“When I was a girl I wanted to be Emily Brontë, but this summer I am reading Kafka with all the enthusiasm of an adolescent.”

A sentence in the direction of dying, as all sentences are.

A story that starts with the previous story’s ill-focused litter of parental possessions. And ends with some crystallisation of recognition.

This story seems to give a palimpsest of ‘literary obsessions’ and a mundane Yorkshire Moors community, like, one minute, seeking all references to Jews in Brontë novels, the next studying some local puckishly called Mr Kafka in the village, studying him at a distance between bouts of teaching English to a multicultural world the Brontës never knew,… A similar palimpsest in the previous story was Classical Greece and mundane life. Trying to reach those Wuthering Heights beyond one’s dizziness with feet still on the ground. A story about resisting kinship. But I have found another kindred spirit for Yellin: Pflug. If you enjoy Yellin you will enjoy Pflug. And vice versa.

“…lit up like Christmas. I am filled with nostalgia for something I never had.”

“He was both quintessentially English and essentially foreign.”

…which is the ultimate palimpsest of pedigree, I guess. Pale, pearl, real, repel…Perela, Perella. To fix by the lapel…to reap…

I hope I am not going over the top, but, for me, this is one of the great literary stories in English, resonating into areas uncovered by any genre, literary or otherwise. It is is a perfect pearl, meticulously crafted, sad, knowing, aware, covering this book’s collections of bric-a-brac, maps of life, growing, seeking that ultimate pedigree of self, via the magic of nemonymity and nameship in mutual transcendence. This story’s characterisation is sublime.

A book left unread, is a treasure to keep. You will ever be able to anticipate it, ever on the brink of book. This book.

“She kept the curtains drawn in the front room, to prevent the carpet fading, and it seemed, more than any room I have ever known, to be inhabited by its silent furniture.”

I love front rooms, but this is the best front room I have ever encountered. A Jewish family, seen via the eyes of the daughter, with an older brother who fails the strictures of such a family. The sad fact is that they all fail such strictures as well as themselves, but the brother makes a show of it. Again, the making of plans or the imagining of destinations that never work out. Another immaculately characterised scenario, where sentences keep the only direction that they can keep, and the girl’s long hair is plaited and unplaited so very meaningfully without (until the very end of the story) any meaning at all. Curled, too.

“So I abandoned myself to those void Sunday afternoons of childhood which give us our first taste of futility and make us long for death.”

This is *the* masterpiece of Anti-Natalism as a precisely crafted miniature of that modern rebellion against life, a rebellion that didn’t have a name even when the author wrote this story only a few years ago. It is simply so supreme on this subject, it gives some mileage to positive Natalism itself and for taking life by the scruff of the neck paradoxically to produce such exquisite depression … although, all the time, this story remains perfectly depressing. No mean feat. A character study to die for. And a time of quiet ticking parlours or slow moving piano sonatas.

I am convinced that this author is both the disciple and furtherer of Elizabeth Bowen, and I can give either of them no greater compliment. I recently renewed my acquaintance with Bowen: Shadowy Encounters of a Third Kind.

“Is there no escape from our heritage, […]?”

A Jewish ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’… simply that, combining all the angst of furthering families, including people like ‘velour-voiced’ Uncle Oswald, a bit creepy, coming and going within the pattern of your life, but someone you need to absorb into a family map or tree, to make sense of it. Someone you need to rubber-stamp, keep in touch with, despite what he is. His smug entitlement that never dies as long as there exist memories of it, like Doreen’s, to further it. But Doreen is not the main protagonist; she is a bit player. Yellin’s fiction is wonderfully a bit like this story’s Shoematic: just put your reading mind inside her fiction, then wiggle it about…

Loved the idea of a Rolex going for a dive, as if it does this separately from Uncle Oswald who owned and wore it!

There is so much in this story, it’s like the white elephant of its vast house, a practically uncleanable, ungardenable house and grounds in miniature, a visionally unmargined elephant in the room of literature. So much to tell you about, you would find it far more satisfying to read for yourself, and far more cleanly, succinctly absorbed, with no need to weed around Mrs Rubin’s greenhouse. The almost love affair of mother and daughter, the seeking of references to Jews in that vast room of literature, the unsuitable suitor for the daughter’s hand, the inscrutable finances, the unknown outcome that resonates on after the story finished. The perfect characterisation: they seem like real people walking inside the dollhouse of your mind.

Tamar Yellin is the disciple and furtherer not only of Elizabeth Bowen but also of Anita Brookner, Elizabeth Taylor, Katherine Mansfield, Ivy Compton-Burnett … And of something far more inimical than even those writers as a gestalt, something untoward but gracious that underlies the words. Something awesome that the author herself might not recognise. Her eyes do not frighten like a deer’s. Her foot firmly on the pedal, despite appearances.

“Sometimes she likes to be a princess, sometimes she plays at being a peasant. / Yes, I said, but me she expects always to be a prince.”

A finely tuned tale of miscegenation between the English narrator (unless I misremember, the first male narrator in this book) and an Italian woman, a union with one child. Considerations of finance, religion, custom, outlook, that crisscross this text with this book’s amazingly pointilliste particularisations expressed in a smoothly textured literary language. A reconciled miscegenation of language and subject, pixel and purity. Found in translation.

This book also stays on the screen of your mind like TVs used to stay switched on in the early days of its novelty so as to disperse loneliness or embarrassed silence. Even if only with the test card showing.

“It is easier to tell lies in a foreign language. Which is surely why so many people pray in Latin.”

“She watches the clock as it slowly peels off its hours. Every fifteen minutes make eighty pence. Fifteen minutes have never seemed so long.”

It’s as if the female protagonist has plunged her hand into Elizabeth Bowen’s ‘Inherited Clock’ for the pain of its stigmata. This is a story textually racier than the others, a SF dystopia of drought amid our English mundanity of dentists and supermarkets. Yet it resonates with the finite and infinite of earlier palimpsests, the dependence upon finance ticking away: a mouth of money, a sense of anti-natalism, the sentences reaching their point of dying for. Each work with its own musical Dying Fall.

“To Greta, pain is not a matter of degree. Once it starts, it may as well take over.”

“Very gently, Mr Applewick let down the lid, which sloped in now like lips do when the teeth are gone.”

Even before I read that sentence, I had already compared this story’s eponymous piano tuner to the dentist in the previous story, reiterated by Mr Applewick’s ‘teething troubles’ in setting up a makeshift telescope to study the stars when he was younger. His treatment of a ‘sick’ Broadwood piano owned by careless people, itself has the meticulous (astrological?) harmonics of this whole book, and one worries that, as the years go by, one will lose track of which felt words the author of this book put in which drawer, especially after all of it is retuned eventually. Thankfully, though, this is not an ebook and nothing will have changed since these words were properly printed. A universal cataclysm is the only factor that could possibly affect this book that otherwise will outlast us all. The only tuning required is that of my own life’s resonation with age and the compartmentalisation of approaching death, especially in this reality of Applewick’s (God)forsaken universe of diminishing returns and vanishing stars. I felt comforted at least by the prospect that, even if Applewick turns out to have done a botched tuning job, the result still might be the sound of one of those dincopated Avant Garde pieces of music I have long loved!