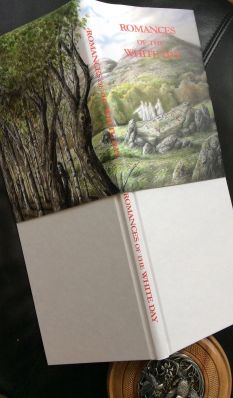

Romances of the White Day

A real-time review by Des Lewis

ROMANCES OF THE WHITE DAY

Stories by John Howard, Mark Valentine and Ron Weighell

in the Tradition of Arthur Machen.

Sarob Press 2015

I have just received this book as purchased from the publisher.

All links above are to my previous real-time reviews upon the subject.

I intend to conduct a real-time review of this book and, when I do, it will be in the thought stream found below or by clicking on the title of this post.

ROMANCES OF THE WHITE DAY

Stories by John Howard, Mark Valentine and Ron Weighell

in the Tradition of Arthur Machen.

Sarob Press 2015

I have just received this book as purchased from the publisher.

All links above are to my previous real-time reviews upon the subject.

I intend to conduct a real-time review of this book and, when I do, it will be in the thought stream found below or by clicking on the title of this post.

1. Meditation in the Streets

“He had not wanted to give her cause for any sorrow. As he continued walking Snow realised he had never asked her name.”

The first section of this novelette has fully gripped me by the London Adventure lapels and I want this tantalisation to last as long as possible before continuing to read it. I sense this work is something special, special even from this its author whose work I have grown to relish more and more over a number of years now. It has the rhapsodic mystic undercurrents to London of endless suburbs radiating from the city centre, as Snow is invited to attend a party in an unknown part of this London, a party held by a long lost friend who is about to get married. The journey is evocatively conveyed, and I feel in my bones that the story itself expected the main happenings within it to involve this friend of Snow. But the story is waylaid, as Snow is also waylaid, waylaid by a church in the vicinity of the friend’s house, and a woman who helps him on his way, after giving him some unusually refreshing water. The friend’s party then becomes just a passing event.

I don’t intend to itemise the whole plot from this point onward, other than that Snow yearns to meet the woman by visiting the church again. However, its area of London remains mysterious – and unknown to most atlases and mapbooks that he seeks out, except one…

Not helped by the intervening years and the London Blitz.

Wonderful.

You’re on your own now with the storyline of this novelette, although I do intend to report back from time to time on the page below.

“They always seemed slightly distracted, as if searching;…”

An Ackroyd sense of London as a living character, here in fiction, thus somehow de-fictionalising it toward truth? I am eking out – savouring – this text. And, like one of the leading characters, I, too, am imbued, in this second symphonic movement of expended time, with London, but the character himself is writing about it, semi-professionally photographing its fast-vanishing bits, post-Blitz, at a time when you can still spend shillings. He is beset with a church tower’s ‘gothic mirage’ that brings to mind at least a feel of L.A. Lewis, and with adventurous escapades concerning a rare atlas, involving a woman and man in a rare part of London, escapades as if from ‘Three Impostors’. But I am mainly struck with the sense of inscrutable or distracted men hanging about hereabouts, in and out of reality, almost importuning me… Making me feel an elusive allusion I can’t quite grab amid the illusionary leitmotifs of the eventual gestalt I’m striving to reach.

“The whine of the mower, the smell of the cut grass, the bright figures sitting on the benches–”

The third movement, an era where shillings have gone and the Internet arrived, and our hero (a palimpsest of three such inter-narrative, almost reincarnative, atlased-out ‘heroes’) has again been ‘waylaid’, now by redundancy… Where the ‘Art of Wandering’ through an equally palimpsested London takes on a new and unique slant that will last as long as Machen’s own slant in our minds, I guess. Highly haunting, such as the L.A. Lewis like Tower, or Samuels’, a mystic brightness set against darkly Blitzed modernity. An unrequited sense of male importuning set against feminine wiles to steal back what was lost, but which chapter or movement is the Impostor, or all three are? London as Heaven’s Floor. Or Flaw? Whatever, do change what you wear on your feet when you walk on it, I say.

Pages 37 – 56

“But to be accounted an author, more, an artist, a philosopher even, I must draw out some motif, some profound essence.”

Melchior (the narrator) visits his friend Verrall at this genius loci, and unlike in this book’s previous story, he is not waylaid into a different story, since he perseveres with the dangerously cosy-feeling journey towards his friend who is to be a major character, too, I guess, with dark resonances behind his hospitality. And a woman’s later recitation of Taliesin, perhaps unfitting for a Christian church, due to take place, with the Parson himself called Nightcap present…

Now rushing back to the tale’s beginning, I need to recall that this whole thing ignites with Melchior’s ‘chance coincidence’ discovery of a magazine called Seven, and its retrocausal conjuring of this tale in his mind. A tale he has already lived. Moonlit croquet, too?

The language is immaculate and Powys-poetic, without being difficult. As before, I shall try to eke it out, savour its olden timbres in my modern brain, before proceeding to its second half.

Which seems to fit neatly with the end of my review above of the previous story…

“Would you be willing to ‘read’ one of his books?”

As I usually try to do with what I have called these my ‘preternatural’ book reviews, I read this story as well as ‘read’ it in the sense meant by the story itself. “I no longer tried to lunge at the meaning of the words but let them rise from me with all their mystery.” A reader of a book often reads aloud to imaginary others from within himself.

It is more Powys than Machen, I feel, but Machen nevertheless, and something else altogether, “a cone of utter otherness”, a cone zero, plus six with the reader making seven. Upon the various cusps of place, religion, historical time, of pottery with poetry.

Valentine has managed to bring something to us between the precarious margins of tributary floridness and distinctively sublime texture, enhancing our appreciation of sumptuously imaginative literature in cusp with real or meaningful ecstasis.

“Yet we live by myths and symbols. And who changes those, changes all.”

Pages 75 – 85

“To books that never were.”

Factored in with Valentine’s Nightcap and this author’s own Weighell, we are now introduced to Midnight, Adam Midnight aka by his real name, someone triangulated by several coordinates intriguingly summoned through fictional gossip, his own artistic output, dubious or salacious or darksome connections spoken of by others in truth or exaggeration, an artist whose work crossed the line, such as the eponymous and reconditely discovered illustration for which the narrator bid at an auction until beaten by someone willing to pay sky high for ridding the world of its existence, an illustration connected with an item from Machen’s own real or imaginary bibliography…. And talk, too, of his most frightening Giacometti stick man made from ready-mades and white marble…

“I had lived out my favourite opening to a story.”

The Narrator’s pursuance of the gestalt of Midnight via the darkmotifs of his own narration seems to become a veritable orgy of references in these middle pages, such as some apocrypha to ‘The White People’ that are more real than the story itself, themes and variations on Poe, MR James, a CASian style at times, a painting as if by HPL and arcane book lists as if HPL himself had forgotten his own list and concocted a real one for Weighell to give to his narrator, and art allusions galore, plus a real lady musician connected in more ways than one with circumstances of the eponymous illustration, and music that transcends even that of Erich Zann, I guess, and you may think this is an overbearing mishmash, but it isn’t. It becomes, for me, an avant garde happening or cut-up or installation of text convincingly masquerading as audit-trailed Decadent Literature of the old school. Scarily, thus. No mean feat.

No chance to eke out or savour, now.

“Strangely, someone had marked the loose stones with the initials A.M. ”

I ‘am’. An “is” State, spreading, spreading. The words now exponential with not even any longer a pretence of linearity, but still artfully disguised as conservative Horror Fiction, while its own Doll’s House, inside the reader’s head, swelling out the skullbone, smashing icons and statues alike, expanding, destroying the familiar references that seasoned Horror readers like me have loved. Out-ligottianising ligottian. Nature’s ready-mades. Running rampant. Rampage of references. The middle pages were comparatively mild, in hindsight. And now it has become a unique way to create from literature a nightmare’s own nightmare.

Still, it ends ‘gnomic'; indeed the lady composer IS once described with this word, as I sometimes AM ‘stilted’, too. It is as if that Erich Zann of a lady has created a disarming coda to her Weighellish symphony of radio noise. The narrator crossed the Severn Bridge after all to reach her, to become her.

———

The three excellent stories in this book are quite different variations on the theme of Machen, as much as Machen had many variations of himself.

end