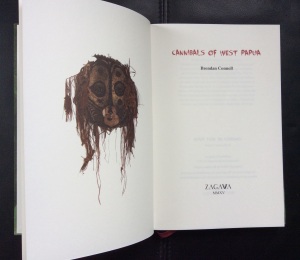

Cannibals of West Papua

Just received this book as purchased from its publisher.

CANNIBALS OF WEST PAPUA by Brendan Connell

ZAGAVA MMXV

My previous reviews of Brendan Connell HERE

My previous reviews of books published by Zagava HERE

I intend to real-time review this book and, if I do, my comments will eventually be found in the thought stream below or by clicking on this post’s title above.

On its last page are these holy words: “Printed in a strict edition of 124 numbered exemplars, 10 of which are hors commerce, and an edition of 26 lettered exemplars bound in finest leather”.

I

“One should not judge a people’s goodness by how they are attired or bedeck themselves. Christ himself carried no cross about his neck…”

This first chapter seems to be an easy slip-in to the book’s story, but with this author’s welcome densely-textured traces of thought and style. An optimum of traction and accessibility, telling of a stunning location of, yes you guessed it, a part of West Papua, where a missionary priest arrives as transported by someone’s almost homemade helicopter from the time when that someone used to work for a mining company…

Evidently, the new missionary is a bit sniffy about the missionary efforts so far upon the half naked natives heretofore.

As I read on (while slowly savouring the text), I do not intend to itemise further this book’s plot in such detail but attempt, in my own way, to catch its ‘dream’ whether or not it is one that was intended by its author.

“Wheat does not grind itself into flour,”

Firstly, before I swan off into a literary ‘dream’ about this work, I should issue an apology and a correction of my first comment above. The new arrival – Dom Ramiro – is not actually a missionary priest but someone more administrative sent out to this outlandish place to sort out the lack of success of the current missionary (Fr. Massimo).

I am caught up with the story and feel I need to read this book faster than I am, which is strange for a Brendan Connell work, in my experience.

One senses peculiar goings on here, and I am wondering if this is absurdist or didactic. Or even a Graham Greene-like novel. It is possibly all three. Whatever the case, it is delightfully crafted as prose and dialogue.

“a list of words found in the New Testament but not in Homer,”

“The side of the mountain we came from the Patntrm people call Good Mountain. This side they call Bad Mountain.”

One mountain, two names, I assume.

This book, I sense, also has two sides, (1) the adventure story (guns and man-eating) mixing Rider Haggard with Graham Greene amid didactic repercussions and (2) the absurdist or ‘dreamcatching’ side. I am not sure yet which is going to win, assuming the existence at all of such a dichotomy in this novel, a dichotomy possibly paralleling that between God and Savagery, Author and Text. Still, the plot is engaging enough, so far, portraying yet another dichotomy: (a) the intractable bigoted inculcation aspect of missionary work (Ramiro) in narrative interface with (b) its ‘softly softly catch the monkey’ aspect (Massimo and his assistant Nun). I think there is a saying: Don’t chew your betel nuts in case God is inside them.

“One man’s heaven is another man’s hell.”

Dom Ramiro is essentially priest after all, at a stricter outward level of Christian dogma and with more openness-to-modernity than that of Fr. Massimo. So, I was right from the beginning about him. Ramiro who is grappling with his own apostasy, beset by a bloody scene in dream-like vision, as the two priests with their hedonist pilot’s ditching of the helicopter are brought closer to the root and branch of the terrain and its competing savages, some savages more amenable (like the Long-Ears) than others. I note a few brilliantly vintage Brendan-Connellian tracts of text with individual rarefied words he uses here and there while the story takes itself toward a level of its own apostasy to be more than just an adventure yarn?

“The horror of the march was in sharp contrast to the surrounding beauty,”

A chapterful of spear carriers. As they face the direly gory scatology of eschatology by cannibalism and cage, the two priests tellingly show their differing emotional and spiritual colours under such duress.

Vividly described. Swash buckling as well as revelatory.

One item I would draw out is the propensity of bodies and faces to accrue and then fix the physical evidence of the emotions within, cannibals and non-cannibals alike.

“Only by abandoning all hope can I hope,”

“…a smile at once sad and ebullient, like an acrobat performing in a graveyard.”

The text explodes now beyond itself and becomes a form of semantic terrorism. Wild enough to eat the reader. No? Well, almost. All this, for me, extends beyond mere cannibbles into vast gulps of kinetic cannibalistic power as well as the crucial nut chewed out from within the reader’s thinking brain itself. Massimo, in face of all the carnivicious aberrations, retains his stoical spirituality, while, by contrast, we are treated to Ramiro’s bloody backstory fuelling his now frantic (sometimes erotically fabricative) armoury of rosary twisting and intense Godly prayerfulness.

This book is promising to become a series of veritable philosophico-religious Socratic dialogues transmuted into brain carnage, I anticipate. Or perhaps it has peaked too soon and will merely revert to type as a Rider Haggard yarn? We shall see.

Forewarned is forearmed. This book’s title is clue enough as to its nature, I guess. And Aickman’s arguable connection with cannibals is indeed a tea party by comparison to this book’s Connellibles!

“Even clouds fear that they might turn dry and stones hope for tenderness.”

A welcome calming of this text’s tenor, more in tune with Massimo’s stoicism than Ramiro’s fires of Hell, although by the two priests being offered man meat we have perhaps the inevitable comparison with the Christian Eucharist…and more, from Ramiro’s point of view.

This is a RELATIVE calm, allowing us to learn more by dialogue of the nature of the impending dangers and the cannibalistic practices.

This is one hell of an experience, this book. So far.

Only this work, surely, can combine acts of extreme cannibalism with the art of Alchemy and “esculent incest.” Finnegans Wake as if translated by Marcel Schwob? Roman Catholic Transubstantiation blended with pagan sin-eating or a philosophical (Cartesian) pineal gland as the seat of the soul or my earlier mention of the swallowable nut in the reader’s brain, now described as a ‘red pit’, a mutual transfer of text between all those writing it and absorbing it, including the still unpitted characters seeded within it. (My concocted proverb above about betel nuts now seems like a premonition).

Massimo (apparently an Alchemical or Transubstantive version of a previous character by this author called Fr. Torturo of whom I am not knowledgeable) now assumes his own solitary Pilgrim’s Progress through the jungle, while Ramiro remains consumed by his inbred obsessions while still within the cage…

And there are some mighty powerful descriptions of the jungle in this book as well as of the various eschatological and scatological factors. And I therefore wonder if the text’s freehold author (as opposed to his leasehold team of authors – as raging shards of himself – who work within the leafy green kernel of the book) had any direct research trips to such environments before writing this book. I would imagine he must have done.

Equally, is he a Roman Catholic to be able to create so powerfully that religion’s extrapolations of faith as tools of his plot? Or is he now a lapsed version of that, thus fuelling any didacticism and a competing non-didactic absurdity of equal strength – both of which this work seems to me, so far, to be suffering like convulsive indigestion or like semantic terrorism stowed with unseen spiritual suicide bombs?

“Now he stood naked, smelling of old blood.”

Ramiro re-mired in his own past leads us into his future, a present day blossoming from within the dogmatic nub or unconsciously blasphemous pit within him, leading us towards an ultra-didacticism of a Swiftian Modest Proposal sensibility, but, here, that sensibility is not even ironic!

Towards, too, a hyper-misanthropism of the strongest distillation, Moliere notwithstanding. And only 124 other readers can share this with me, it seems, can share this unique literary extrapolative text of pure rage and tasty human entrails. I feel privileged. Again, no irony.

“The technological progression that modern man prides himself on is simply the retroactive genius of those who came long before.”

“He had to find his way home. But to do so he had to turn assailant – to do what was not in the domain of a man of God to do. So then was he a man of God as he professed? St George had killed a dragon, yes, but only in order to save the maidens of Silene.”

A tussle with conscience, as Massimo continues his rite of passage. Tussling with a drunk God as well as an angry One. Tussling with the intra-instinct of men, one of whom he is. (Coincidentally, earlier today, I reproduced Uccello’s 15th century painting of St George and the Dragon, in connection with my on-going review of Marcel Schwob’s ‘King in a Golden Mask’ book HERE). What are such coincidences telling me? I sense, at least, a theme of ‘masks’ in both Schwob and Connell, as well as the physical parts of a man’s meaty frame housing parts of the man’s mind itself?

And Massimo now seemingly addicted to the red pits, too, while his meetings with Tree People etc. take on an aura of Monty Python-like conversations, via a magic language medium, before he makes each of his spirit-hungry, wonderfully described swoops upon any individual headman’s skull-kernelled nut within.

“‘Who are you?’ he asked.

‘I might ask the same.’

‘No one comes here after dark.’

‘You are here.'”

“It is said that one must have confidence in God for Him to grant one’s prayers.”

Fr. Massimo, in this substantive chapter, visits the Underworld, burdened, I only infer, with his own Torturous backstory, to neutralise his own failing to save the soul of his Nun companion, the trappings of his normal Churchly Christian methods having indeed faltered when praying for her survival from illness.

Some readers will see this as a significant episode, a tactile engagement with some mission like Christ’s facing out the Devil, to succeed in which will solve the ills of our world.

For other readers, it will be enjoyed for its own sake, a Miltonic, Hieronymous Boschian, Dantean, Devil’s Detective Unsworthian, Monty-Pythonesque journey with all manner of horrendous or scatological creatures to which I cannot do justice here, including midget bugs with priests’ faces, and 150,000 bespoke Hells, and all manner of wonderfully envisioned Kafkaesque red tape, leading at this chapter’s end to an equally wonderful conceit worthy of King Solomon’s wisdom as another Modest Proposal!

“…he should be able to overcome? And if not – well, he was certainly ready to give up his physical form, that bag of bones he carried around in the attempt.”

We reach a growing culmination, with Fr. Massimo “seeming to hover between fire and aether, knowledge struggling to incubate truth within him.” The syllables of this text possibly hold mystical power; “a single phrase causes a war in which thousands or even millions are killed.”

Temptation, carnal or monetary, works against the Foes, tempts them with what seethes inside them, female flesh or mining for ore? Or reading texts such as this one full of unholy succulences? I note that the lettered version of this book is made from the ‘finest leather’ – begs the question: whither such leather? “– a syrupy confused slurry of incoherent vivisection.”

I empathise with the mining didacticism. After all, my own novel features such ‘HAWLING’ with, in my case, it is Azathoth who’s bubbling infinities at the centre of this hollow world.

“But the world’s hollowness seemed to have taken on a new resonance.” And Dom Ramiro is rightfully hawled over the coals of his own Eucharist.

This remarkable experience of a novel seems to have been written whilst tapped into its own “raging waters and booming light.”

Half this novel’s soul: baroque art for art’s sake. The other half: something else altogether completely held within Connell.

And no space for Greene or Haggard in the Dysfunction Room.

end