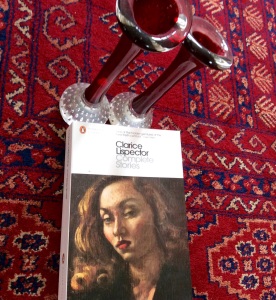

CLARICE LISPECTOR – Complete Stories

Complete Stories of Clarice Lispector

“One of the hidden geniuses of the twentieth century” – Colm Tolbin

Penguin Classics 2015

Translation: Katrina Dodson | Introduction: Benjamin Moser

When I read this book, my real-time review will be found in the thought stream below or by clicking this post’s title above.

My previous real-time review of the stories of Silvina Ocampo – https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2015/05/13/thus-were-their-faces-silvina-ocampo/

“It has wings, but doesn’t land anywhere.”

Like this book, I imagine, before I read it.

This is a story of Luisa and her third person singular thoughts detailed by place and character in a similar style to those detailed in the anti-novel by Brian Aldiss I am concurrently reviewing here.

This Lispector work has the same strength of obsessive meaning, depicting her male companion’s need to overcome her as a visitor from Porlock, combined with the strength it gives me (woken by a flow from the text’s cold spigot) to be back reading this book after its first brief story, as he who abandoned Luisa is due to be back, too.

“It seems mad. However, Daniel also had his reasons. Suffering, for him, the contemplative, was the only way to live intensely …”

Another version of the Visitor from Porlock, as Christina meets her own Kubla Khan in the shape of Daniel, who wakes her up from acceptance of an ordinary life with Jaime. This text itself is obsessive as well as being ABOUT obsession, strangely combining the detailed relentlessness of the Brian Aldiss book mentioned above and my current reviews here of Truman Capote’s otherwise naively conversational Gothicisms of character. The inevitable ‘dying fall’ at the end by seemingly natural means of her destiny unlocking horns with Daniel’s destiny makes this all the more powerful a return full circle.

This story seems both naive and mature, with the latter adjective trying, like Christina herself, to outgrow the former, but failing …. For the moment.

“I go down every path and still none is mine. I have been sculpted into so many statues and haven’t frozen into place…”

“She turns on the light. He feels humiliated, deeply humiliated. Now what? it would be so easy to explain that it had been a light bulb…”

The girl either interrupts the boy’s fever dream – or is part of it

– or both?

Only for her to return afterwards as a reminder of that dream.

This story is a highly rarefied dream in itself about a dream, making it seem like a real dream, if that is not a contradiction in terms, with our Earth, to the sound of flutes, giving birth to babies like an inversion of a song cycle by Mahler, I feel – the one loosely translated as Songs for Dead Children,,,?

I sense this book is now in a haunted overdrive or poetic outgrowth. It feels like a story written by the boy about his dream and its waking aftermath, written while still within the dream rather than after it.

Waking is the ultimate Visitor from Porlock?

“Here is where the actual story begins.”

So, this story seemingly interrupts itself, representing the watershed that was evident in ‘Obsession’ between Jaime and Daniel, and now here between Jimmy and the lecturer named D_____. A Hegelian theme and variations of that earlier story, where ‘equilibrium’ is now explicitly ‘disrupted’, using those every words.

I’m still fathoming, though, the significance of the leitmotif of Jimmy’s ‘elongated skull’…

Maybe that will become clearer as the gestalt of all the stories in this book develops?

“…his life amounted to a pile of shards: some shiny, others clouded,…”

I had not looked ahead in the contents to the various story’s titles, so this one came out of the blue, interrupting with an interruption, thus ironically or paradoxically healing the gaps between the first few stories.

This is another theme-and-variations of Christina-Daniel, Luisa-Porlock, Girl-Dream, Jimmy-and-I, all as destructive-creative symbioses.

And Death the only true Interruption? The elongated skull?

“: the dark, shadowy waters could be centimeters above the sand just as easily as they could be obscuring the infinite.”

There seems something defiantly natural in the ironic progression of all these stories so far, here the woman’s break or escape being a circular one, almost a terrestrial or tidal magnetism taking her back to her twelve year old marriage. Making each story a musically ‘dying fall’ of escape (here with a a ship) – followed by a paradoxically reluctant welcome for escaping that escape.

“For instance: why is it that they, with those beautiful wings, don’t fly higher? Could it be that those wings are powerless or did flies lack ideals?”

A tantalising threnody of Flora’s sojourn in a cafe, thinking of her imputed daughter and the man she is there to meet, again in full circle like the previous stories. A threnody that accretes absurdity with coffee flavours and Debussy dreams. An Excerpt as another form of Escape, until interrupted by completion – if any interruption can be expected rather than unexpected?

“For we are animals yet we are animals disturbed by man.”

I think that may summarise the stories so far, here included in the first of two amorphously semantic, almost artificially musical, letters from Idalina to Hermengardo…

There is something man-kindish about the recipient’s name, based on my knowledge of language roots. A messenger, too. As we reach some apotheosis of Waiting as Hope resonant with the Brian Aldiss book just reviewed … “a man without substance”, these two letters, too.

Free yourself from passions by reading such letters as fiction.

Put a symphony on pause. Or, rather, do not listen to it at all, and it will be perfect as music forever.

“Sensitive people are both unhappier and happier than others.”

Here the letter, by Gertrudes (Tuda), is to a female doctor whom, although visualised, she has not yet met – but she eventually meets her before the end of this story intervenes. An amorphous yearning, a need to seek, if confusedly. It is almost as if all these stories so far are now personified as a gestalt within the shape and place of that doctor – or she is Tuda herself by the time she reaches that age? A crystallisation. A bending of the future towards the past. An explicitly altered (interrupted?) destiny.

“His little head is contorted, his eyes are open, staring at the wall, obstinately.”

This section of the book reaches, I guess, its inevitable coda. Where the destructive-creative symbioses reach the lips of two drunks, one clumsily trying to summon the other’s good side regarding his scions and his legacy. An instant that is explicitly forever, horror that the moon still shines when you are dead, praying for a sentient death that enables you to close the lid, from inside, of your own tomb.

Unless the last line of the story in this book has a misprinted false start of an ending, it surely shows me that I was not crazy to dream up an interruptor from Porlock from the very start of my review! A drunken one?

The next section of stories is headed FAMILY TIES.

This book has 85 stories in total under various section headings.

“Oh what a succulent bedroom! she was fanning herself in Brazil.”

A young woman’s quasi-‘Molly’s Soliloquy’ of self’s physical and mental extrapolation, blending her ‘Yellow Wallpaper’ half with her vainly polarised ‘Lilliputian-Brobdingnagian’ half in her bedroom and the restaurant. The otherwise beautifully smooth text often falters or stutters (both healthy and ill, by turns, like the woman herself in interface with her husband), faltering or stuttering with exclamation- and question-marks that don’t end sentences plus shape-shifting words that morph in and out, among similes and conceits, beyond their actual semantics or joined-up syntax of sounds.

With this story now factored into this book’s earlier section of FIRST STORIES, a whole new literary, almost psycho-Rabelaisian, world is beginning to emerge.

“And as if it were a butterfly, Ana caught the instant between her fingers before it was never hers again.”

Anna’s epiphany on a bus when spilling her shopping and breaking the eggs and seeing a blind man chewing gum, as if he is smiling and not smiling at her in turn. It reflects earlier stories of a woman’s ordinary life in convulsion with eventual return to it. I think the word for some of these stories is ‘stoical’.

All laced with fever dream of a botanical garden. Magritte. A sense that if this story took place in Japan instead of Brazil it would make even more sense, if still richly oblique.

“But whenever everyone in the house was quiet and seemed to have forgotten her, she would fill up with a little courage, vestiges of the great escape — and roam the tiled patio, her body following her head, pausing as if in a field, though her little head gave her away: vibratory and bobbing rapidly, the ancient fright of her species long since turned mechanical.”

I wanted to quote that whole paragraph, arguably demonstrating that this parabulous fable, written from the point of view of a chicken, succinctly deploys many themes and variations of this book so far.

“–no longer that blinding light from those coiffed and perky nurses leaving for their day off after tossing her like a helpless chicken into the abyss of insulin–”

Another symbiosis of wife and husband, she with her routines, a ‘Yellow Wallpaper’ aura of sickly anxieties, but diligently ironing, as well as reaching an obsessively and relentlessly anti-novelistic or Henry-Jamesian epiphany about perfection in either giving away or not giving away beautiful roses.

A relentlessness that hypnotised me.

But what is back? when Laura tells her husband it’s back at the end. My theory is that it is the pat on that very ‘back’ from her doctor … or a drink of milk. Probably both.

————————-

HAPPY BIRTHDAY

“And at the head of the large table the birthday girl who was turning eighty-nine today.”

My mother has recently turned 89 and, although my family is nowhere as large as the family that attends this amusing party, I can emphathise with it. The homely, potentially caustic, interaction is conveyed well. The disappointments of the birthday girl, as well as the acceptances. And the type of statement addressed to her at the end – “see you next year, Mother” – reminds me poignantly of Laura’s “It’s back” at the end of the previous story. Concerning this book’s treatment of death.

“‘Mama, look at her little picture, poor little thing! just look how sad she is!’

‘But,’ said the mother, firm and defeated and proud, ‘but it’s the sadness of an animal, not human sadness..'”

A gender- and size-inverted King Kong discovered by an explorer in the depths of Africa, setting off all manner of intangibly deadpan emotions that only this writer, I guess, can summon through a sort of unique writerly otherness that I sense is underlying the texts so far in this book. Under-lying as a form of exaggeration that tries to make you believe that what was caught was tinier and less human than it actually was, while, in fact, by suspecting a double bluff in a sort of fisherman’s mime, you believe that it was bigger and more human than it actually was.

The text now reaches levels of meticulous otherness exceeding all previous levels of this book, here an extrapolation upon a prediction of the Dirk Bogarde character from the film ‘Death in Venice’ being watched in a restaurant by a PoV other than his own, except the ending throws some doubt on that assumption as if watcher and watched are participating in ‘The Grande Bouffe’ rather than DiV. Being watched watching, as the ‘garçon’ attends to him…

“Her own shadow was a black pole. At this hour that required greater caution, she was protected by a kind of ugliness that hunger accentuated, her features darkened by the adrenaline that darkened the flesh of hunted animals. […] She’d eat like a centaur.”

Like a centre, too?

This is like being in the head of a fifteen year old girl transmuted by some literary alchemy into a brainstormingly theosophical epiphany (cf Damian Murphy), elongated like this book’s earlier skull – when she imagines she is followed by four footpads amid seven mysteries, between leaving home and getting to school, akin to today’s well known dangers reflecting the dangers of Lispector’s yesterday … or vice versa.

I take it back – reading this work is not like the reader being in the girl’s head but, rather, her being in yours!

I suspect only Lispector can bring this off.

“: it was easier alone.”

Family ties – as in ‘Happy Birthday’ – knot together the polarities of humiliation and attraction, the act of touching as well as of repelling, a mother with her daughter, the latter with her skinny son as well as with her husband.

A dysfunctional scenario depicted by a dysfunctional story, one dysfunction cancelling out the other by dysfunctioning it, and vice versa.

One needs to read anew when grappling with the Lie Inspector.

“After dinner we’ll go to the movies,”

“…as if the bitterness of sleep had given her satisfaction.”

Tentative definition of a Lie Inspector: using the truths of some words to search out the lies of other words. A special alchemy that this author uniquely wields, with a language that often resembles nonsense as the perfect sense.

Here, in this story, night is something that befalls you (dishevelled and dreamy) and day something that ends up wearing you as such – or wearing you down? The boy’s interactions with his parents, with money, debts, a lost old lady, his school desk, girl friend, movies, are all interrupted by the story’s last sentence with the promissory note of meaning still to pay.

“Have some more potatoes,”

“…progress in that family was the fragile product of many precautions and a handful of lies,”

Another ‘Happy Birthday’-type family (one a skinny 19 year old girl) on the brink of epiphany, breaking up, coming together, careful, careless, a fleetingly false ageing, all in interface with masks as lies.

Three fabulously or parabulously masked figures enter the family’s garden to steal hyacinth flowers. Reminds me of a recently reviewed scene in ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ where masks themselves were stolen and the thieves wore the stolen masks on leaving the shop.

Well, to my mind, we now come to the first truly great story in this book so far. It tells of a man burying a token unknown dog to absolve his abandoning his real dog. He is watching those entering a church while digging a conscientiously shallow grave for the dog. He is clear, with no loose ends. But his personal tussle as seen by us Is complex.

“By not asking anything of me, you asked too much.”

He is doing something merely so that he can undo it, a man with a dog or a dog with a person, an emotional grappling with spirituality and philosophy – while the grappling’s mathematical implications are deployed with no loose ends? Yes, since the unique literary alchemy of Lispector is in creating a purity that STAYS a purity even when it becomes a complex tentacularly spiky metaphor or fable or parable reaching out in many directions.

“So I sinned right away to be guilty right away.”

“Fists in her coat pockets, she looked around, surrounded by the cages, caged by the shut cages.”

In many way, a parallel with the man’s experience in destructive-creative symbiosis with a dog in the previous cage, here the woman seeking the hatred in her own heart that deserves to be expressed because of some man’s hatred for her, his hatred as she interprets his love, as she now reads her own love, trying each animal in the zoo by turns to create what is now called, here, ‘mutual murder’. She even tries a mechanical monster called a roller coaster. This is the apotheosis of pain, I feel. (I once created a zoo in my published novel, in the grounds of which is the only place where you would be clear whether you are dreaming or not; my zoo didn’t stop you dreaming, but at least it DIFFERENTIATED between dream and non-dream, so you could know where you stood; elsewhere in the world you dreamt and woke, but you never knew which was which; I get this feeling with this whole book that has become my zoo of animals to be communed with story by story.)

So ends the section of this book headed FAMILY TIES

The next section of stories is entitled FOREIGN LEGION

And my real-time review is continued HERE