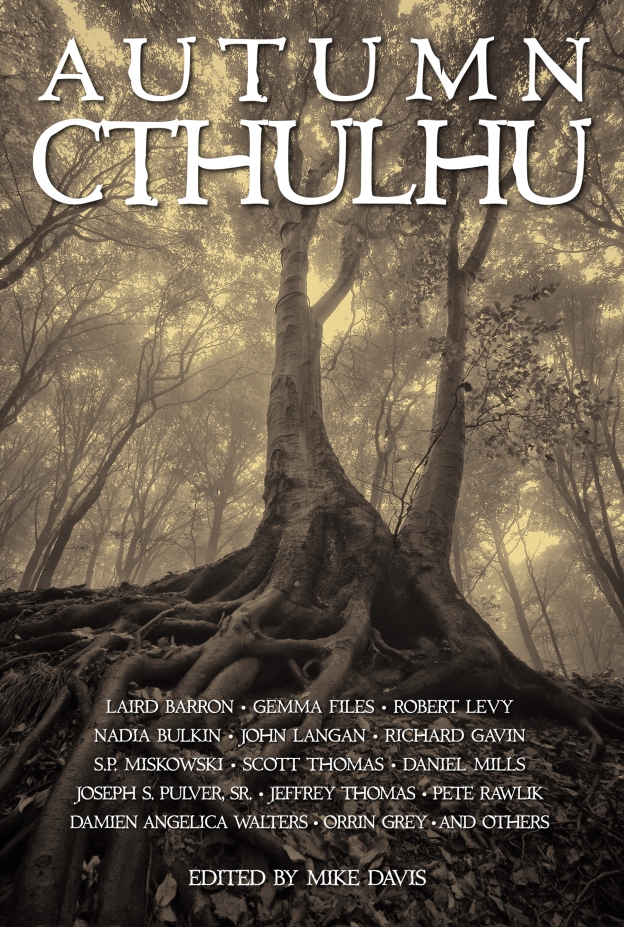

Autumn Cthulhu

Lovecraft Ezine Press 2016

Introduction – Mike Davis

The Night is a Sea – Scott Thomas

In the Spaces Where You Once Lived – Damien Angelica Walters

Memories of the Fall – Pete Rawlik

Andy Kaufman Creeping Through the Trees – Laird Barron

There is a Bear in the Woods – Nadia Bulkin

The Smoke Lodge – Michael Griffin

Cul-De-Sac Virus – Evan Dicken

DST (Fall Back) – Robert Levy

The Black Azalea – Wendy N. Wagner

After the Fall – Jeffrey Thomas

Anchor – John Langan

The End of the Season – Trent Kollodge

Water Main – S.P. Miskowski

The Stiles of Palemarsh – Richard Gavin

Grave Goods – Gemma Files

The Well and the Wheel – Orrin Grey

Trick… or the Other Thing – Joseph S. Pulver, Sr.

A Shadow Passing – Daniel Mills

Lavinia in Autumn – Ann K. Schwader

When I real-time this anthology, my comments will appear in the thought stream below.

“Local folklore maintained that the apples tasted like blood and that they contained human teeth instead of seeds.”

A workman-like, quite well-written yarn to tell around the Halloween campfire, but I found it confusing and melodramatic. Some nice moments with them apples and what is inside the pumpkins.

“…the episodes of my life that I like to believe are (relatively) shaped by choice, will power, and intention might actually be connected dots governed by some great unknown is terribly unnerving.” — so, this story also leaves me with a fateful trust that urges me further onward to do such dreamcatching in this book, a book with such an enticing overall title that made me buy it in the first place. (HERE are some of my findings regarding Autumn as the gestalt of the whole of the WEIRD genre…)

“….and wind rustles through the trees, turning the leaves to a rippling fan of orange, red, and yellow.”

A haunting, touching, sometimes unbearable, portrait of Alzheimer’s in the husband of Helena. Remove the He and you are left with Lena? I wonder.

“I do.” Does he remember?

Telling interaction with their daughter and grandsons. Hiking tracks in the woods, a doe, a deer, with fur falling like the Autumn leaves. Simply told, but with a complex memorable oscillation between decisions at the end, between sad and happy. To do or not to do. And were those odd forces with which he communicated healing forces or otherwise? A very satisfying read.

For me, an Autumn Ode transcribed in simple prose with its own strophe, antistrophe and epode.

“The pie was heavy and the filling thin. It ran across my plate, spreading like a glob of orange slime that had seeped into the world from some nearby hell dimension.”

A pumpkin pie, made from pumpkins in the Scott Thomas story?

A relatively short Autumn-ripe essay upon the self as a writer of cosmic horror, a captive within the very school where he is sometimes allowed to teach creative writing to the twelve year old children. A captive of his own madness, too, a madness that he recognises for what it is, unlike the previous story’s Alzheimers husband. Or is that vice versa? But which is which, who is whom? Teaching the young to own their own madness, until we cease to recognise such madness and see it as an accepted norm of real cosmic horror – by having been such tutored and fallen young once ourselves?

Tellingly provocative … until the already shaky reading-ground I find myself standing on is snatched away by further reading in this fell book?

“Everybody loves me and everybody else hates me. I know who’s who—”

A rather clever literary exercise with a blonde taut young woman cheerleader as narrator, filtering an Updike or Roth mentality, as she tells of the trampoline accident that puts paid to her activities, the backstory with her father and Machiavellian mother – and now we have a momentous character: the nefarious Steely J (a mutant version of her childhood imaginary companion Jesus?) who plans a consolation meeting with a favourite famous actor for her now cancer-ridden Dad. With the onward thrust of Speedy Gonzalez, this story, with many neat turns of phrase and knowing transgressions of wholesomeness as in a Losey film, reaches an arthouse conclusion of “patronising contempt”, cruelty and horror.

All is copacetic.

“Rage makes a beautiful painkiller.”

The word was used in the Laird Barron story above.

“…manically thrashing his head in the dark as a clump of hair and tissue tried to chew its way out of his neck.”

There is something richly elusive about this textured portrait of politics in today’s world where many feel that one needs to grasp the nettle, become almost evangelical, radical solutions (Trump or Corbyn?) needed as there is nothing to lose – here seen through the eyes of a young woman called Cass and her captivation by Rick and his new fringe politics movement, to take control of the world's "fishtailing car." But this story itself knowingly fishtails itself, as the readers feel they need their own evangelism to triangulate its meaning, and perhaps they never do. As the characters, with their idealistic thrust and, for one, a token of moral support like a forebear's athletic gold medal, entering territory of lobbying for votes among seemingly even more evangelically fringe parties within a maze or odd circle of some theosophical quest, I infer. The story itself, instead of DESCRIBING Reagan's bear in the woods, actually BECOMES the bear that we are trying to transcend. I found the whole vision disturbingly irresolvable, tantalisingly a personal confirmation for me as well as a defeat.

(Brainstorming: 'Pro Patria!' upon the life-death seesaw, but at which end?)

“Not one of us is poet enough to name the loss of Karlring.”

“Earlier we took risks, stared demons in the eye. Suddenly thirty years have gone, spent typing, vision wrecked from computer screens. The edge gone dull.”

The bear in the woods of the previous story transmogrifies here to old bear Karlring, a story that seems an apotheosis of nostalgia of oldening horror genre writers, male and female. under the posthumous post-humus smoked meat jurisdiction of he who now radiates his influence from the smoke lodge. You must visit the smoke lodge as conceived by this story. A vision that you can sense seeping into your skin, then into your bones, a tale that is itself a walking talking yellow or golden Autumn as many remember Karlring, himself in the real world, the last time they saw him, outside this story, supposedly, they thought then, terribly ill, but now in hindsight ripe with a risen Fall – and I know know why we, he and I, once chose anchovies!

A story of utterly pungent power.

“A dream remembered is not the dream itself.”

“Above, shoals of starlings circled beneath a flat, cloudless sky.”

This tells of a man, about my own age, I guess, and he has lost his wife, and has visits from his daughter and son-in-law. Dealings with the neighbours, still able to muscle up to digging a fire-pit, crossing swords with a curmudgeonly neighbour and his dog, watching new neighbours. And a concept develops, somehow, almost autonomously, although it is put into one of these character’s mouths, about all these houses that ribbon our communities and who lives in them, or what.

In tune with this book’s earlier spaces of the doe, I recall a phrase I have often used since I was a young man: “You live a day a day to put life in.” Here, Alzheimer’s is called “creeping senility”, and I am honestly spooked by this creeping story. I can give it no greater compliment.

“The darkness didn’t absorb the light so much as ignore it,…”

“…and it soon became clear I was traveling in spoked circles.”

And the circle notched Into place suddenly with the meaning of the acronym DST in the title dawning on me. A circle like that in the Bulkin story.

Surrounding a stock romantic relationship triangle, including a very well constructed observatory contraption in the woods, in the story’s terms, constructed as if by a Prophetic Heath Robinson, as if, too, an attempt at a ramshackle triangulation of cosmic coordinates, like this review. And tied into a disco record the playing of which once, years ago in the relationship’s backstory, spanned all these factors with its own prophecy. A workmanlike cosmic vision, one that did not personally inspire me, despite my admiring some of the descriptions.

“Something from beyond the bottom of that hole…”

I loved this story instinctively. A genuine blight story resulting from the extraction of an azalea from a widow’s garden, an action that results in a sink hole and stench, with the sound of somethings monstrous chugging nearer. It literally seeps Autumn amid the mulch of the garden and this woman’s own Autumn of her years, someone who recently nursed her husband towards inevitable death via his own sinkhole of pancreatic cancer. The whole story lives and breathes – and suppurates. Healthy horror.

This is an important story, not necessarily for a nephew’s funeral wake as a Halloween Autumn tale (including the resonance with Fall and the concept of humans gathering to celebrate one of their own dead), but for the amazing vision that arrives in the world’s sky after a strange storm, like a Sistine Chapel ceiling, like fossils of elder gods, or something far more intrinsic. That vision in the text is extended and quite awesome – and the feat of describing it and its “maybe-faces” is staggering. Above all, its potentiality. A seminal work, I feel, with many implications for this type of literature and, dare I say, for our world at large.

“How fragile, humans. Like bugs crushed in an instant under the steps of vast, unthinking forces… neither of which could really see nor fathom each other.”

“Hey, they’re the only gods we have evidence of. Maybe that’s how they died… fighting over who was going to be our god.”

———–

Scott Nicolay quotably said recently: “Lovecraft is the fossil fuel industry of Weird Fiction.”

I said in reply: “Maybe Lovecraft is Azathoth still lurking at the Earth’s Core, I wonder.”

I think we may be both wrong.

“This way, when he runs up against it, we’ll have the earth helping us.”

A story overtaken by the bear of a longer work, a work that transcends story, novel or novella, as it seems to expand beyond as well as within poetry, bromance, cosmic horror, Blackwoodian combat with a monster worldwide, a tranche of time spanning a character from 12 to 50 sown and sewn with internal bold texts intended to infodump, and a sense that this is a story that is highly personal to everyone involved, especially its freehold author, and it gives off a sense of inspiration. A deadly determination to get all this off some bear’s chest, Richard Adams Shardik’s chest, Aslan’s chest from Narnia, as well as Yeats, Eliot and Cormac McCarthy. That bear in the woods from two previous stories in this book. The tumult of Tumnus. Wielding a ‘do’ like this book’s earlier ‘doe’. A father-son symbiosis via the spear of Martial Arts, Reassurance but don’t tell distaff Mum. The Broken Circle. Ardor, as they say in America. The nature of literary celebrity. River monsters. The tug of the bait baiting you, as you struggle with this ever elongating text like a river monster itself.

“It’s been a while since a work of fiction has affected him this profoundly. During his visits to nearby creeks, part of him remains inside the narrative. Or it remains inside him:”

“Both of them had it, though, a… a fire for language, for what you could do with it. Sometimes, I imagined Dad’s work as a great library, like the one at Penrose, all Gothic revival, its windows ablaze with light. And sometimes, I would picture Carson’s work as a bonfire roaring in the center of a forest clearing, its light falling on redwoods a hundred feet high. They recognized that flame in one another.”

The fire of flu. The fire along treetops. The unfamiliarity of water. Vast visions that hit and hit at you. You can’t put this down, like a King work. But on it goes, on and on. Relentless, irritating, but rubbing its inspiration off on you.

“…to know that there’s animal in the reeds, keeping pace with him. He isn’t certain what it could be. A deer?”

Crucially, though…

“You know, there are times you begin work on something, and right away, you can tell, this is going somewhere. There may be some bumps on the road—let’s be frank: there may be blown head-gaskets, and washed out bridges, and sudden thunderstorms—but you can just about see your destination at the outset.”I shall now eat this work. Literally. Seriously.

But the final vision of the lion man still pervades me. Like Blackwood’s Centaur does.

I, as reader, through the pareidoliac eyes of the well-characterised love-damaged summer worker protagonist, also feel as if I am one of the “lingering summer people”, while the “intimately connected” locals upon this tourist Great Lakes island regroup following the island’s “season of drunken days and inebriated nights, and now the autumn came, stripping the tourists like so many leaves.”

The descriptions are wonderful, and the vision of the Islanders’ hidden village as microcosm (or Langan ‘anchor’?) of their passions, sorrows and dark truths is hauntingly memorable, together with the entity that may be as large or small, as monstrous or sublime as I wish, should I see it.

Another cosmically significant story for this anthology. And by “prognostication or command, cosmic intent or happenstance, this was the way things were going to be.”

This is a both a hilarious and poignant portrait of a woman, from her own point of view, of her relationship with a live-in man friend, with marriage in mind, and he reminds me of myself at least in his poor d-i-y skills (particularly plumbing) and with his head in the whale-shaped clouds! But I can’t see myself wanting to watch blobby cartoons! Such a description – with its wittily sharp turns of phrase concerning character and bureaucracy and about the place where they live together – is, however, only one aspect about this story.

There are darker, more cosmic and more thoughtful shades that fill this believable woman with disarming visionary power. Her stoical wandering, seeing from afar the place where hippies go to die (utterly haunting), and suddenly encountering a building of apartments that is reminiscent of an ocean cruiser. There also seems to be a fearfulness about life, a fearfulness that stems from affectionate memories of her father and of his tale to her during childhood of a giant’s accretive vibrations that he concocts to disguise an earthquake’s horror – but now, today, there is a parallel accretion of “slow leaks” of infant terror-visions in the ocean cruiser building into which she is tempted almost in rebellion against somethings she’s leaving behind – leaks that no plumbing can stop, leaks building up into a frightening grown-up flood of images…

An entertaining fable but with an amorphously indirect moral that, for me, has more force than if the moral had been direct and confidently clear.

“Maybe everyone should be a little bit afraid of the things we can’t explain.”

“The openness of the lane, the visibility of the cloudless sky was too immense, too open.”

This is an honest horror story with its exponential openness, honest inasmuch as its horrors are perfectly pitched to cause terror, and any literary nuances are in the darkly evocative turns of phrase and the sense of love for horror words and soundfest constructions for their own sake, and honest in the sense that the reader is not fingerposted through this outlandish Welsh village, as the Canadian protagonist named Ian is both confused by this place and squeezed by a remarkable concept of a squeeze-stile, crossing a step-stile, too, via the various styles of squeezed fear and missed steps. Honest, too, in that we cannot have sympathy with this protagonist, based on the implications of HIS words, that he had jilted his own stile-squeezed bi-polar fiancee at the altar, with him now come to Wales whence her family derives and unforgivably attending the planned honeymoon holiday alone, the honeymoon he alone aborted. And no wonder the demons that pursue him are inchoate as all fears are, as all squeezed depressions are, and we admire his honesty at admitting by clear implication that he is no horror story character with whom to empathise or sympathise or cheer on towards safety, a safety, without dishonest fear of a plot spoiler, he does, however, reach, despite our not caring whether he did so. And the one he abandoned at the altar, as it were, is now possibly just one of several monsters (so utterly nightmarish in themselves) shambling after him in an honest horror story. And I let out a deep sigh as the two sides of a story’s character are finally brought together by his own vice. But none of that takes account of what is envisaged transpiring in the possibly on-going plot after its claustrophobic text releases us from its captivating style, releasing us into the open. Unspoilt and endless.

“…and though their thick eyelids remained closed, Ian was sure they were seeing him.”

“Put the pieces back together, fit them against each other chip by chip and line by line, and they start to sing.”

In the same way as I make stories sing, I hope.

But this story, for once, defeated me on a first reading (all my real-time reviews are based on first readings) but it defeated me in a good way. I understood none of it or I understood MORE than it meant. Nothing in between. A number of women on an archaeological dig, couched in a stunning literary style that seems to have been engrained in the very ground where they dug. An obstreperous group, debating the ethics — of preserving the bones where they lay or taking them back to the lab for further dismantlement — surrounding the sanctity of human beings or of less (or more?) than human beings that they dug up. Skeletal structures as that very debating point, even to the extent of one of the so-called woman archaeologists found to have a questionable anatomy herself – or himself?

I was entranced by the scientific terminology, while floundering somewhere in a no-man’s-land sense of Lovecraftian horror as a cross between, from earlier in this book, Wagner’s dug stench-hole and Gavin’s creature with breasts and a comically small, stubby penis.

“these people were barely binocular—”

“Ever since I was a little kid, I’ve had a habit of opening books to the back pages first.”

A story of the theosophical circles or wheels of existence in Bulkin and Levy – and, hopefully, the Broken Circle of Langan. It is also an intriguing and disturbing tale of a daughter entering for the first time her father’s house where he had lived divorced from her mother, a house like a shed, where the evidence of his nefarious habits seen to scream out at her, until she climbs down into tantamount to Wagner’s hole in the ground, to understand his battle on her behalf against the fate she once herself set in motion and now frighteningly irresistible…

Cosmic Horror has the essence of retrocausality, I propound: something one learns from the whole of this landmark book … so far?

————–

My Forever Autumn: https://nullimmortalis.wordpress.com/2012/09/20/forever-autumn/

My Perpetual Autumn: https://nullimmortalis.wordpress.com/2014/02/02/perpetual-autumn/

Perpetuo Au-Tumnus

“No, you don’t. And you are out of future,…”

“Every minute or so, Atticus can see Nyarlathotep, hear him, walking in circles…”

This is a top lathe yarn or a vice one like the Gavin, crazily jamming with various pieces of metal squeezed together and shriek music style, but I dream most here of jagged Jagger. Lots of good nightmares and screeching vocatives. Curling off the shavings of viced wood into mutant Halloween pages.

This is the book’s coda, two stories too early, the wildest one to go out with. So, I guess I should have started from the back after the previous Orrin Grey told me to do so. The Pulver he is a master of such crazy jamming, and always trying to trick me or the other thing. Till some Fell Baron disguised as Nyarlathotep decides finally which it is to be?

“Somewhere in it was the bull of rage.”

“…but the alleys swarmed with them, hundreds of them, with bodies made of corners so you see them only where they block the light.”

Another coda for this landmark book: a marvellous dream of childhood’s despair, a delightfully poetic rhapsody in prose as well as vision of the monsters on the landing outside a boy’s bedroom disguised, I imagine, as shadows or aunts – a work stemming, for me, from a blend of Truman Capote’s early work and the protagonist Proustian boy’s unrequited love for a mother whom he awaits awake, as if eternally, yearning for an unspoken goodnight kiss to allow him an unbroken circle of sleep. Here that kiss is to be, I infer, a dreadful curse, a fairy-tale betrayal….?

“She extends her hand to him with the palm open, a tea-cake nestled in the thatch of wrinkle and bone.”

(This author also had DE PROFUNDIS in The First Book of Classical Music Horror Stories)

————————–

Lavinia in Autumn (Sentinel Hill) by Ann K. Schwader

A short poem as a perfect coda in itself for this optimum AUTUMN CTHULHU.

Yeats eat your yeast out. Or your heart.

“….for she

Who traced their patterns…”

——————————–

My wife’s latest quilt is still taking shape, one she has been working on while I have been reading AUTUMN CTHULHU

end