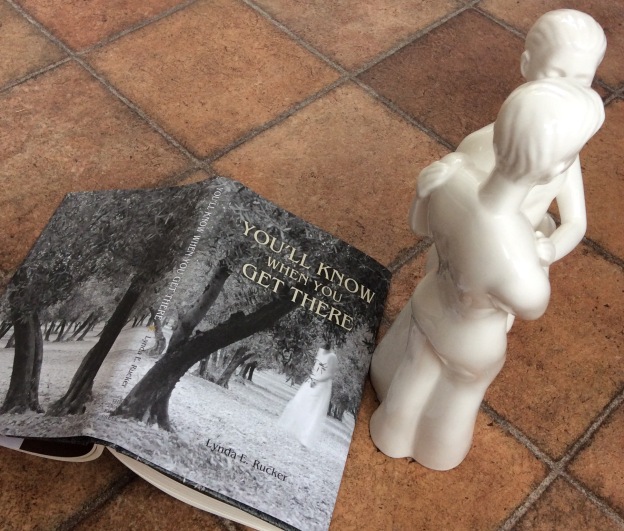

You’ll Know When You Get There – Lynda E. Rucker

A collection by Lynda E. Rucker

The Swan River Press MMXVI

My previous reviews of books from this publisher HERE.

When I real-time review this book, my comments will appear in the thought stream below.

“Ruben’s fingers had looked like that as well, she recalls; only paint — instead of ink-stained.”

I had a double take when I first read that, Rubens or Ruben, indeed, it is Ruben, her deep Platonic lover, this third person narrative in the name of Aisha (the Ayesha of the ‘She’ she fears she may become), so utterly third person singular, but she imprints herself as a first person singular round and round and upon the reader’s skin with neat homilies and wise saws of emotional modernity that become a rhapsody of weird fiction (Walters, Moraine, and many others?), weird fiction of the distaff that so perfectly populates the pain and pleasure of the weird-turning world today, this the ‘she’ with a ritual-sinuous tale of herself and Ruben, the painter, and his own ultimate self-harming that exceeded her own, and she takes and gives from all quarters of spear, distaff and vampire; we are all receivers of her tales, but only if you are the receiver tuned into the right channel do you travel it right…

I feel with my real-time reviews, that I have managed to fine-tune my receiver to the optimum. And this work stays with me wherever I move that fine-tuning needle next upon my written-upon skin. You see, it is the only story featuring a chance hitchhiker given the immediate chance to actually drive the car (wherever that hitchhiker wants), and thus the only story giving a chance reader the chance to write it.

You’ll know when you get there.

“The modern world ensures your identity clings to you as surely as your fingerprints.”

“It was just an ordinary gate, and the other side was ordinary too.”

Bearing in mind the American protagonist’s everpresent and explicit “trauma” at once losing, through emotional entropy, his beloved ready-made family, and now staying in a cottage in the wilds of Ireland, this is also the ordinary story it seems to be, and the rest of it is just his trauma-fed imagination?

Whatever the case, I feel relieved that to transcend any curse of widdershins all you need to do is walk with the sun, the path the earth ever follows with or without your own contribution, thus cancelling out any path you shouldn’t have taken, any gate you shouldn’t have passed through. Even if it means stretching you against the grain between tree and tree to do it.

“In the end, we all find ourselves in the same place.”

“…and one word distinguishable above the rest — her, her, her — and she never knew that three letters, a single-breathed syllable, could be weighted with so much hatred.”

At first I feared this might be another stock documentary haunted house investigation. In many ways it is one, but not stock. It is probably the most genuinely frightening such story I have read. The documentary extracts, some disagreeing with the others, are interspersed with the narrative of a woman, a literature student teacher – and her husband who commits suicide quite out of predictable character. The nature of the horrors in the hatefully prehensile house cannot be given justice to here, and references such as Fuseli and the Ouroboros symbol merely distractions from something genuinely and irresistibly horrific that somehow lies beyond the text even if it is conjured up by that very text. The finale where she escapes into the presumably welcoming normal outside city is a masterstroke. Can you tell I like this story?

“…and somehow regal despite it all.”

An idyllic hot endless Summer memory, of ghostly train tracks, campfire horror stories shared, curses expected, lostling or even changeling inferred, these young people in- or post-backstory, in or out of confused or jealous love — and it did not seem to matter that I myself became confused by this work’s darkly entrancing theme and variations upon the Sourhern Gothic (please see my recent review of the complete stories of Flannery O’Connor), confused because I must be too old to follow such goings-on.

“What a funny place the world was, that this could be the most mundane of journeys for them and one of the most exciting of her entire life.”

A darkly charming story. Fern, with a learned stoicism, travels from her native America to England, not only with a learned nostalgia for the stories of M.R. James but also one for the BBC productions of those stories in the 1970s, whose latter production sites she intends to visit, as she now travels with excitement, via Liverpool Street, and where I live along that rail line, towards the Norfolk coast. We learn a lot about her character, her dreary life back home, and now in the ‘signal box’ room at the inn, and the kindly-intended gentleman called Mr Ames who befriends her with his own Jamesian enthusiasm, but inadvertently deprives her of her aloneness of discovery. A very subtle character study of Fern by Fern, and how she summons the ghost of her ability to stay and not return. A ghost more frightening than she intends? You’ll know when you get there? (Possible spoiler here).

———————-

A new day. And a new gestalt for the second half of this book?

The Queen in the Yellow Wallpaper – Lynda E. Rucker

“Each generation that came into possession of it made additions and architectural embellishments and what stands today is a sort of hideous discordant symphony of a house.”

I love discordant symphonies! And I love this story (about a married couple gone to a house called Carcosa to care for the husband’s ‘sick’ sister), imbued as it is with many ‘comforting’ horror tropes (including Robert W Chambers’ ‘King in Yellow’ and Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘Yellow Wallpaper’ (the latter story often being used in academic feminist circles as a recommended text for study – a fact that resonates with some of this story’s themes)). Here it does not seem to matter that we are steeped in those potentially stereotypical horror tropes – the pleasure comes in this story from embracing them and their embracing you. Meanwhile, I sense this author is suspicious of the ‘avant garde’ in Art and Literature (something I have noted before, I think), yet whether by design or, more likely, by accidental synchronicity, the author makes her female narrator seem to become subsumed within the sick sister’s avant garde play being written around her, making her, the narrator, into the eponymous Queen herself? A sort of embrace, despite disgust, of the experimental (paradoxically within a seemingly formulaic horror story!) and the outré. This story really makes you think on several levels (as does the Gilman story in its own right).

(Later) I apologise – the writer I was thinking about regarding suspicion of the ‘avant garde’ was Helen Grant, not Lynda E. Rucker. See my review of Grant’s ‘The Calvary at Banská Bystrica’ HERE.

Or mine? I don’t think this otherwise well-written story was written for the likes of me. It seemed contrived, with modern day romantic machinations, a heroine haunted by a wood down the end of the road and by pre-Roman Britain. Like the previous M.R. James inspired story (for me, far more enjoyable), it is an innocent abroad, an American woman in England, unsettled here not by Mr Ames but a strange woman in the wood. And by a wayward English husband and the woman next door. Not sure what else to say about it.

“…back in the gentle chaos of the crowded family.”

Rucker is often full of rhapsodies. Rhapsodies sometimes upon the edge of hard-consonantal near-rationalisation, also upon the soft edge of never coming back, of becoming attenuated, distaff-diaphanous…

This is one such story, where I floated between the once durable sororal loving relationship, grown edgier since the older sister came back early from service in hard-consonantal Iraq and the younger sister almost disappointed that she can no longer ‘recognise’ the sister she once loved accompanying, despite the age gap. And the lakeside cabin their Uncle once built, where I guess the two of then now see a version of Rucker painting the rationalisation she sees below the lake’s surface, some small-town version of Suffolk’s Dunwich, from beneath whence unsalubrious church bells sound…?

Who sinks to find the other? Ruck and rack or Josie and Ellen.

Rhapsodic or near-rationalised with an old war’s attrition? A story that tugs you further beneath its own surface.

: remember that there was nothing that she had to get up for, and sink deeper Into the bed, deeper into sleep.”

What I was, in hindsight, hinting at the end of the previous story review seems here to be apotheosised. One house sublet in another woman’s name, and a lifelong recurring dream of a house haunting her from the few days days before Christmas, a house, with landing and grandfather clock, straight out of an Elizabeth Bowen Christmas (my favourite writer ever – my house for her here) and I wonder if Rucker is in Bowen’s soul, or vice versa, like the synergy of these two houses or two realities? Bowen also had a version of a fractured modernity in her fiction alongside the haunting and the aloneness to be disrupted by an Ames or a woman in the wood, like the Oregon reality here, a bus journey on a whim, leading from the hard edge of dream unreal to the soft edge of dream real, or vice versa. The tantalisation of never knowing. Sublet by time’s clock on the landing or blocked by modern contraptions, only thinking back through all these stories might give some clue of the whence and the whither of a deeper rhapsody. You’ll know when you get there.

I will now read for the first time the introduction by Lisa Tuttle and the book’s story notes. I trust they will give me more food for thought but, meanwhile, I leave you.

end