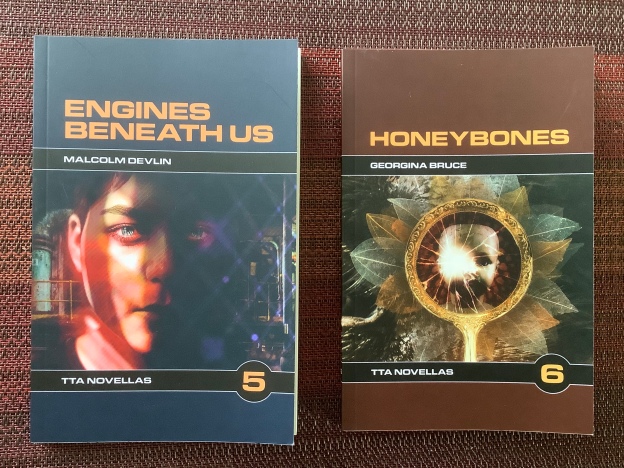

Honeybones / Engines Beneath Us

TTA Novellas

Malcolm Devlin – Georgina Bruce

.

My previous reviews of TTA PRESS publications: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/tta-press-interzone-black-static/

Covfefe permitting, my reviews of these novellas will appear in the comment stream below…

ENGINES BENEATH US

By Malcolm Devlin“We took care of the city, we took care of Mr Olhouser, and he took care of us.”

When I was a small boy in the 1950s, and often put to bed too early, I created in my mind or BY my mind a hub outside the working class house where we lived near the recreation ground or green, a hub in the pavement that reached beyond itself into a machine room below our terrace of houses from where I could control somehow the roots of my downtrodden background in what then seemed a communication with the rest of the world, where I seemed to work at these things, as perhaps this novella’s Mr Olhouser worked. I have since related my memory of that hub to the then future Internet. Now the memory has darker roots, those relating, in this novella itself, to when my own, as well as Rob’s, Dad’s “overalls smelt of iron and oil and earth.” So reading this just now has taught me a lot, as well as hinting to me why my story ‘A Halo of Drizzle Around an Orange Street Lamp’ in the Big-Headed People book was written, a story wherein a night picnic was arranged on the green whereon these houses bordered… and why the events of that night were later recorded in the Family Bible …But this novella varies it: “A circle of orange streetlights against a velvet blue black sky; the thin white halo which surrounded The Works. The street was still and Old Elsie had gone.” You will never forget Old Elsie, the bag lady, as described by this novella, as told by the story of Rob, as narrator, and of another boy who comes anew to the Crescent called Lee. And The Works as a sort of hub of the Crescent (part of today’s working class or gang-controlled streets), a hub for the city with machines throbbing below: The Works that are sometimes more like mining or hawling rocks, rocks grinding together. My Welsh forebears were coal hawlers and miners. Miners of mine. And the tunnel-back two up two downs or back lane houses, even semi-detached, reflecting each others’ interiors, housing insidious cultures that do more good than harm, I now hope. A culture like today’s coronavirus (that orange drizzle and halo mentioned above!) and we surely need Mr Olhouser’s ‘tonic’ (“clawing at my lungs, reaching deep inside of me.”) even more! Notwithstanding the teeming mice and their pink squirming young. Rob’s encounter with the true nature of the Works and wondering if he shall ever meet Lee again, as he now sometimes does or does not, in later life. Headstrong and crime-sneaky Lee, in those boyhood days, with his comic heroes and rumours of what he had once done to his Mam, Lee who then tempted more than he should have done vis à vis Mr Olhouser. Childhood seen from a distance, it says somewhere here. Even a taste for opera in the case of Rob’s Dad. Lee’s narration about following some strange antics by Old Elsie are melodramatic info-dumps of dialogue, but is he acting, speaking by rote, pretending, still tempting the untemptable? Slow and quick at once. The city that is older than the law, hawled by such Crescent forces. Fragments re-jigsawed from those lodged in deep memory. Someone elsewhere in this novella has a metaphor about jigsaws, that I cannot find now, but this ostensibly was beyond what such a humble working-class mind might have thought of. But it was part of the hawling beneath her feet, I guess, making such humility the greatest wisdom of all…the greatest gift of wisdom from among many such in this bespoke haunting novella. Bespoke for each reader. I have merely told you mine. My mother, too, when I was that child with whom I started this review … “She’d set a fresh glass of tonic on the cabinet. She told me I should stay in bed, and she reached across to feel my forehead, as though either of us believed I might have a temperature.”

“The day resumed as though it had stopped to watch me fooled.”

My previous reviews of this author: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/tag/malcolm-devlin/

— from the Devlin novella above, the alter ego of the author of which is responsible for the cover art of the next novella….

the under the house

HONEYBONES

by Georgina BruceFOR THE ENDLESS GIRLS

Pages 9 -23

“…a house of mirrors and it was entangled with its selves, a pattern looping inwards, up stairs and through doorways and round corners, round and round and up and down. That day the houses had locked together.”

“Gripping the banister so her knuckles glistened.”

I wonder whether I should revise Scofidio’s Knucklebones here?

I wonder, too, if I should revise Bruce’s The Book of Dreems here?

This is Anna, a bullied school girl, I THINK, and dreemy peeple that remind me of the sort of doll my own children once had back in the 1970s with a cord in its back whereby if you pulled it out, it quite slowly sprung back with an incantation of these squeaky words: “Ah ha, I’m coming apart!” No, suddenly I realise that I am wrong about this, for this voice-cord was not in its back, but it joined the neck to the head, but served the same purpose of giving voice to such confused despair of coming apart. Which this text is threatening to do the same to me as I try to fathom the nature of Anna in this house with her mother and Tom, the latter being a sort of Dad figure who calls her beautiful, and puts his hand in her hair. And I ride the visions that attach to her dreams and realities. But who is Thew? And is this dream or drug, to cope with her teenage traumas? I feel a bit responsible for her already… as if reading more of this novella will make things worse for her? Or were things never that bad for her, anyway, thus making the word ‘worse’ not so good?

“come into the under the house”

“; she was so dangerous her head had been caged.”

“Everything’s different. Even time. Even time is different now.”

These pages – whereby we learn more, often by the dint of a nursery rhyme soul, about at least the thrust of relationship between Anna the narrator, her ‘Honeybones’ Mum and Tom, and maybe Thew, too, and a fictional woman called Rose – are a theme and variations on the phenomenon of self-isolation, its tensions of nature, its sporadic escapes like Anna being trapped, say, in a tree with a male merge, or in the house of mirrors to which they somehow returned from the earlier funeral and this house’s entrapment aids…all factored into our increasing poetic knowledge of Anna’s bullied backstory as her current self perceives it: through the filter of drug or dream, or both? Or something transhumanly unique that only this novella knows about?

“Roaming around the house I felt as though I was air, thin air poured into the shape of a girl. I lost sense of time.”

(That broken voice-cord…?) “, I’m broken. I don’t even feel like a real person anymore.”

A pocket full of posies,

A-tishoo! A-tishoo!

We all fall down.

Pages 42 – 61

“The cully king is raging mad. Come into the under-the-house. The thing the king I love to sing…”

And hearing that nursery rhyme about more than a single Rose in my head just now perhaps indicates who the culling ‘cully king’ really is, today of all days! Carrow sounds like a cough or a corona. This must have been written, though, long before today, for it to have been first published a few weeks ago. We are given, meanwhile, further dimensions of the house and the funeral and the nature of Rose (Bruce?) — and who erotically is it touches Anna Carrow or who is it makes Anna Carrow touch whoever it is; Tom (like Ian elsewhere?) has a notebook, amid pages that gradually become blank and the above quote in the book itself gradually fades from black into grey then blankness by means of the actual print’s reality. There are now blank books on the shelf in the story itself. And I could kick myself, when I only said ‘drug or dream’ above; I should also have added disease and dementia and desire as further possibilities. There is much talk of madness in these pages now. But whose?

“…stepping through one house to the other and back again in a thousand reiterations of a footstep. […] The house inside the house opened up to us like walls melting away. […] The hallways unfolded and refolded…”

“You shouldn’t leave the house.”

“And when he [the cully king] spoke, his voice made me feel like I was choking on feathers and dust,…”

“No, I’m a man – and we men are weak, we are driven by our desires.”

My previous reviews of Georgina Bruce works: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/tag/georgina-bruce/