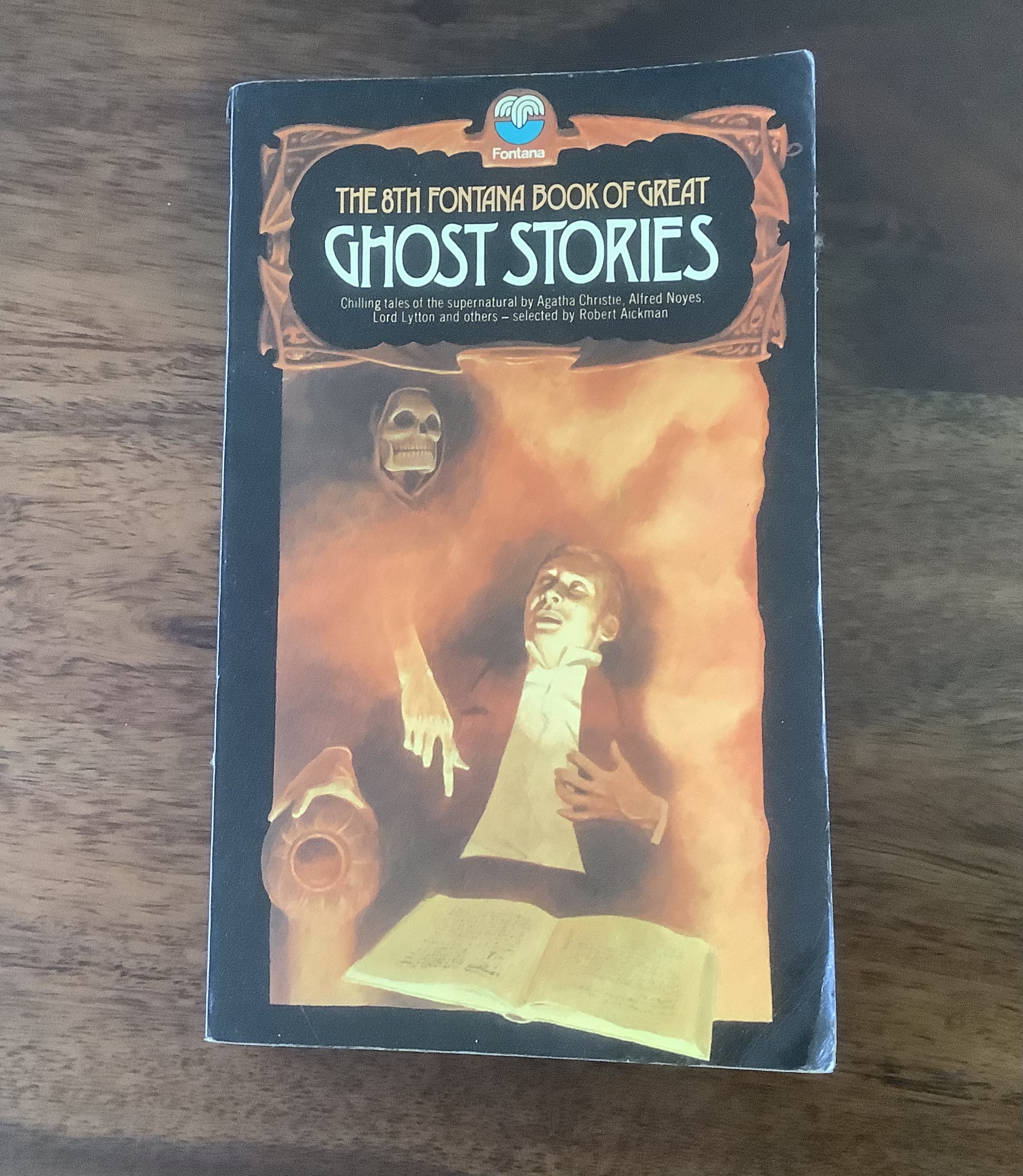

The 8th Fontana Book of Great Ghost Stories, edited by Robert Aickman

My previous reviews of these Fontana Great Ghosts by Robert Aickman linked here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2021/04/30/the-fontana-great-ghost-stories-chosen-by-robert-aickman/

My previous reviews regarding this book’s editor: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/robert-aickman/

My previous reviews of older or classic books: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/reviews-of-older-books/

WHEN I READ THE STORIES IN THE 8th BOOK, MY REVIEW WILL APPEAR IN THE COMMENT STREAM BELOW.

THE HAUNTED HAVEN by A.E. Ellis

“…the glorious panorama of St. Bride’s Bay, as it sweeps round in a majestic curve from Ramsey Island in the north to the Isle of Skomer in the south.”

An otherwise run-of-the-mill traditional ghost story of storms and fishing-boats and superstitious villagers in a secluded double-coved village (one cove said, by evidence, to be dangerously haunted by three nephews and their uncle, as a result of the latter’s after-death vengeance upon the former) – yes, but it also surreptitiously (till now) and creepily connects HERE with yesterday’s reading of this series of Aickman Fontana Books, with the four head wounds as literally telling gashes or cracks! The uncle’s in particular has an Oke gash at the edge of his frown!? …

“, a great, livid weal across the side of his forehead.”

THE RED LODGE by H. R. Wakefield

“Directly I had shut the door I had again that very unpleasant sensation of being watched. It made the reading of Sidgwick’s The Use of Words in Reasoning — an old favourite of mine, which requires concentration — a difficult business. Time after time I found myself peeping into dark corners and shifting my position. And there were little sharp sounds; just the oak-panelling cracking, I supposed. After a time I became more absorbed in the book, and less fidgety, and then I heard a very soft cough just behind me. I felt little icy rays pour down and through me, but I would not look round, and I would go on reading. I had just reached the following passage: ‘However many things may be said about Socrates, or about any fact observed, there remains still more that might be said if the need arose; the need is the determining factor. Hence the distinction between complete and incomplete description, though perfectly sharp and clear in the abstract, can only have a meaning—can only be applied to actual cases—if it be taken as equivalent to sufficient description, the sufficiency being relative to some purpose. Evidently the description of Socrates as a man, scanty though it is, may be fully sufficient for the purpose of the modest enquiry whether he is mortal or not’—when my eye was caught by a green patch which suddenly appeared on the floor beside me, and then another and another,…”

I think the above section from it undertows not only this famously and truly terrifying work but also much of Aickman’s work. Indefiniteness and Ambiguity being the heading for one of its sections. The parents and small son and the nanny and other servants are staying for three months at the eponymous Lodge about which we are told straight from the start that they left before completing their stay because of its haunting qualities, involving patches of slime, and I dare not tell you about one particular entity that will give you “pure undiluted panic” if you tell anyone else about it without their having read the story first. I can tell you about the mysterious door in the garden, though, and the nearby knighted gentleman who comes to their assistance, and the little boy’s lack of fear of the sea previously in Frinton but his utter fear today of the river at eponymous Lodge. Seriously, this story is disturbing and will no doubt affect you even more adversely if you divulge too much to those who have not yet read Red Lodge. (The most I could dare do was reproduce an example edition of Sidgwick that was not red.)

To clarify: ‘Indefiniteness and Ambiguity’ is a section heading in the Sidgwick book shown; the lengthy quotation about it is quoted from The Red Lodge story just re-read.

The gold design on the front cover, thinking about it, is a bit revealing, though!

Pingback: The Red Lodge by H. Russell Wakefield | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time Reviews Edit

MIDNIGHT EXPRESS by Alfred Noyes

“…endless lines of ghostly poplars each answering another, into what seemed an infinite distance.”

This is a small, seemingly classic ghost story that I feel I am reading for the first time (I may well be!), with its boyhood journey from an obsessionally terrifying picture in a story book being read in solitary candlelight as a death wish doorway or tunnel opening (cf this Fontana series’ earlier HG Wells story) to ageing life’s eventual arrival at that very scene in the recurrent visions or covivid dreams of one’s own lethal self and that self’s ineluctability, and it strongly resonates with a much longer potentially classic work that I was reviewing, by chance, about half an hour ago by Torni Maa HERE. The resultant mutual synergy between the two is quite devastating as well as spiritually cathartic!

MEETING MR MILLAR by Robert Aickman

“What about the tennis this summer? Good to have it back, don’t you think?”

“Good to have a lot of things back.”

“But there’s a lot that won’t come back so soon.”

“Yes,” I said. “That’s true.”

I have long thought this was Aickman’s most significant story, but not till today — with 13 years of gestalt real-time reviewing under my belt — had I realised quite how significant it is. A prophecy for our times – from the above to a later exchange…

We paused a moment, lapping coffee.

“Are you clairvoyant?” he asked.

“Not that I know of. I’m probably too young.” He was perhaps six or seven years older, despite all those children. “Why? Do you think I’ve imagined it all?” I put it quite amiably.

“It just struck me for one moment that you might have seen into the future. All these people slavishly doing nothing. It’ll be exactly like that one day, you know, if we go on as we are. For a moment it all sounded to me like a vision of 40 years on — if as much.”

And indeed I had to take a moment to consider.

“But they’re doing it all the time,” I objected. “Now. Well, not this moment. I think not this moment. But you can go up and look tomorrow. See for yourself.”

“It’s not something I particularly want to see. Forty years on.”

It just took a bit longer than 40 years?

Roy is an interesting character, candidate for becoming the classic character in all literature, I would claim, a budding writer tutored in writing pornography by a military man, a budding writer with a mother who wore short skirts, a fashion trend of the era wherein strangely this story mentions both Lloyd George and R.A. Butler in almost one breath. The Brandenburg Square block of floors, where chartered accountants arrive in their middle floors (Roy being in the attic), a strange company of so-called accountants led by the ultimately tragic Millar (Roy says Millar is not ‘absurd’ but somehow he is ‘ludicrous’!), his Millar name with an a not an e, with thugs and other peculiar coves and giggly girls in short skirts, and Roy is having an affair with Maureen a woman on a lower floor who is married with children. So much more that only choice quotes will tell you…if the text’s osmosis doesn’t otherwise work….your own emptiness of will foregone…your thoughts ever elsewhere…

Conceivably it was my first clear apprehension of the truth that is the foundation of wisdom: the truth that change of its nature is for the worse, the little finger (or thick gripping thumb) of mortality’s cold paw.

The men never seemed to be fully dressed. Their clothes were always formal, the garments of the properly dressed professional man, but never (when I observed them) did the men seem to have them all on. It was always as if they were frightfully busy, or much too hot: even in winter, though, there, it is true that the offices were remarkably well heated. I would hardly have gazed in at the gas stoves or whatever they were, but from every open door, it might be in December or January, would come a positive and noticeable wave of hot air as one passed.

His glass eyes and wandering hands spoke truth of a kind, where his lips spoke only cotton wool.

I noticed that the sexes were seldom mixed among Mr Millar’s callers, though once I did encounter a very pregnant girl, horribly white, being dragged upstairs by a man with gashes all over his face.

As we acquire weight in the world, we lose it within ourselves. Maturity is always in part a matter of emptying and contracting. By that standard, Mr Millar, almost weightless, almost adrift, almost without habits (where a baby has nothing else), had passed beyond mere maturity; but contact with him amounted to a compressed and simplified course in growing up. Mine was similar to the real reason why a schoolboy does not run away from the school he hates.

And many more!

A happy ending, though? A Pinteresque playing out of Dirk Bogarde relieved of his role in The Servant? What struck me, meanwhile, is the fact this is the second story in this book that mentions Frinton! Scary.

Seriously, this work is a monument to Weird Fiction, absurdist as well as ludicrous. Movingly emotional, creepy, character-rich and fertile with ever-evolving interpretations from any newcomers travelling between floors. Between times, too.

I’ve often wondered over the years how Roy knew ‘Millar’ was spelt thus, when the Accountants’ sign outside the building did not even contain Millar’s name, but just the dead partners’ names!

There is a connection between Maureen’s part-time job with a Bookmaker and later Bookmaking business by the Accountancy firm and Aickman as this book’s effective Bookmaker?

Pingback: Meeting Mr Millar | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time Reviews Edit

I had been reading recent discussions of trying to avoid racism by naming COVID mutant variants after myths, such as Medusa….then today I read…

THE GORGON’S HEAD by Gertrude Bacon

“…and it is called the Haunted Cavern because none who venture there return alive. Nay, they return not either alive or dead.”

A long game, then. A red alert. Becoming ‘A dead monument to once ancient hope’, I sense. This puckish yarn hides a multitude of possible sins, a yarn disarmingly, beguilingly told to a lady passenger by a 19th century ship’s skipper who is also a confident lady’s man, a man who once faced, when younger, the ‘face of a Goddess’ but thankfully seen it in a reflection, unlike his spear-carrier of a foolhardy companion who faced it face on. Better safe than sorry to go abroad virtually these days, I’d say, even to places like where this cavern in Greece is currently on the UK’s Amber list of destinations… but especially when words are read more than just metaphorically and become lodged in your body for real beyond foolhardy reflection…

THE TREE by Joyce Marsh

A strangely dated conte, where an older type of Indian variancy is applied in a parasitic symbiosis that an anglicised Reita (eventually regathering her sari and face marks of her heritage by the end) invokes as a hoped-for mutualism in the huge oak tree outside and in her English husband in “lovely England”— the latter’s body, strained by having been a Japanese POW, gradually succumbing to death in a separate bed beside hers. The invocation (done with her best intentions or through her grudge against the huge tree? ) serves to cause the tree to become lodged with human blood discovered in its root and branch, and her husband to recover as the tree itself dies, but then, as if by justified reversal of false invocations, vice versa.

I perhaps dare not interpret this work with the eyes of someone who lives today in quite a different world. A world where Nature and Mankind are in some as yet inscrutable symbiosis of parasitism outweighing mutualism — wherever each part of such a gestalt is situated, and whatever their race or creed. Nature has no race or creed, of course?

… from the above insight into Nature regarding the previous story above, the next one, a famous novelette, includes these words concerning a mesmeric power or Brain or Gestalt also first known in the India of the Rajahs: “…it would not be against nature, only a rare power in nature…”

THE HAUNTED AND THE HAUNTERS by Lord Lytton

“— a dog of dogs for a ghost.”

Sorry about the loyal dog. Animals and humans differentiated by their reaction to such powers as the power of this very eccentric work by a literary bulwark called Bulwer. Yet, it is in many ways a very frightening haunted house story, with colours and bubbles and globules and larvae of ghostly activity, with spectral footprints and self-moving furniture and a servant more scared than his foolhardy master the narrator who is investigating the haunted house and underlaid by a backstory of past characters generating such a power, but later transmogrified by a wildly theosophically scientific RANT disguised as fiction with dialogue, and concepts that relate to the gestalt of the Brain as a preternatural explanation for the supernatural. The connections and cross-references of electric or Odic cross-wiring in the mesmeric ether generated by one such a power of human agency to outdo mortality by means of some version of the Null Immortalis…

I sense that my empirical reliance upon the gestalt in foolhardily scrying such power-driven literature, a real-time enterprise like the narrator’s in the so-called haunted house, yes, my own perhaps naive instinctive reliance that weaves through such endeavours does teeter on some brink that this Lytton work brings me ever closer towards! A ‘fiction’ work that is often officially and notably subtitled, “The House and the Brain.”

I wander again through its magnetic text….

“…write down a thought which, sooner or later, may alter the whole condition of China.” Then the whole world? Human brain to brain covividly? Mention of a “certain password”. And of “amber that embeds a straw’’…. “The vision of no puling fantastic girl, of no sick-bed somnambule.” — “Well, observe, no two persons ever experience the same dream.” — “…I half-believed, half-doubted.”

Like the narrator, I must get out my Macaulay to read and give up such dubious self-frights.

Pingback: The Haunters and The Haunted | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time Reviews Edit

BEZHIN LEA by Ivan Sergeivitch Turgenev

Translated by Richard Freeborn

“There’s a man coming, strange-looking, with an astonishing big head . . . Everyone starts shouting: ‘Oy, oy, it’s Trishka coming! Oy, oy, it’s Trishka!’ and they all raced for hiding, this way and that!”

But I feel this is not the Antichrist as the footnote portends, but the Gestalt Brain of Bulwer-Lytton! Here in the wild open air of an Algernon Blackwood terrain, rather than cooped up in a House. One of the Big-Headed People? This is indeed a wonderfully delightful work that I have just discovered, whereby the man as narrator gets hopelessly lost after grouse shooting in the Chernsk county of Tula. The descriptions of the beautiful July day and the eventual sunset and the even more eventual sunrise are exquisitely, memorably picked out, as he encounters — beyond a dark abyss, sitting around their campfire (“as if the darkness was at war with the light”) while they were also baking potatoes — a group of name-itemised and separately characterised boys from adolescent to really quite young who had been tasked with looking after horses through the night. And the man listens, from where they allow him to rest, listens, through the surrounding hush, to their nighttime chatter of local lore, like water sprites, water fairies, goblins, wood demons, human drownings and human joy or pain alongside the small white pigeon of an elusive soul… and I felt cleansed and re-fructified by this work’s darkly shining Gestalt beyond the reach of the suffocating Brain in the previous story, and I was uplifted, too, by the perfect ending of a musical as well as literal ‘dying fall.’

Echoing the intrinsic motherhood of Feklista and her drowned child as told by naive boys around a campfire in the previous story, we now have:-

THE LAST SÉANCE by Agatha Christie

“In the handling of the unknown there must always be danger, but the cause is a noble one, for it is the cause of Science.”

Science being literally knowledge, thus making the unknown known. I said, when reviewing earlier the second of these Fontana books, that it was possibly Aickman’s greatest and most dangerous achievement — and I would now add: in the world of literature as a powerful fount (Fontana) of knowledge. As if at this conclusion of his versions of these Fontana books with the 8th volume (although, for some as yet unknown foreordained reason, I still have four of them to re-read and Gestalt review) he knew it may be his own last séance of science as knowledge, of literature itself, of the dangerous if noble horror in tapping some universal Bulwark of a Brain — here symbolised by the concept of ectoplasm as a child brought back from the dead for its ‘big and black’ mother (Cf The Whitehead Lips) being a physical part of the medium herself not of the risen child now perceived alive — leaving the medium, like this book’s earlier Tree of Blood, shrunk red, if not dead. Left unread. As many of these stories now are.

Aickman is now roped up and finished with Fontana. At least where Time had brought him then, if not having leapfrogged what else he did later? He did not dare turn back in case he was monumentalised in stone too soon?

My other reviews of these Aickman Fontana books: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2021/04/30/the-fontana-great-ghost-stories-chosen-by-robert-aickman/