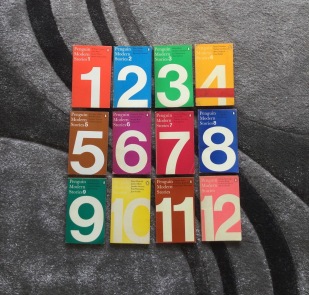

PENGUIN MODERN STORIES

PART THREE, continued from: https://elizabethbowensite.wordpress.com/1366-2/

Edited by Judith Burnley during 1969-1972

My previous reviews of older or classic books: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/reviews-of-older-books/

And other Penguin short stories here: https://nullimmortalis.wordpress.com/26609-2/and https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2021/12/26/the-penguin-book-of-the-contemporary-british-short-story/

When I read these stories, my thoughts will appear in the comment stream below…

BECH IN ROMANIA (1966) by John Updike

“Within ten minutes his phone rasped, in that dead rattly way it has behind the Iron Curtain,…”

And we know we are here in the hands of a master storyteller, prose stylist and hindsight satirist telling of this Jewish writer from America visiting Romania as a cultural delegate, in Romania where they seem to disown their own Ionesco. With vivid, sometimes Romaniac, characters (“Though her motions were angular and her smile was inflexible, her high round bosom looked soft as a soufflé.”) and crazy basement shows with dwarves and black wigs and naked women down the yellow stairs (“Their yellow bodies looked fragile to him; he felt that their bones, like the bones of birds, had evolved hollow, to save weight.”) and a driver who is employed to drive him (“When they went through a village, the driver would speed up and intensify the mutter of his honking; clusters of peasants and geese exploded in disbelief, and Bech felt as if gears, the gears that regulate and engage the mind, were clashing.” and “Our driver would discollect anybody’s thoughts. Is it possible that he is the late Adolf Hitler, kept alive by Count Dracula?”), a driver who is as larger-than-life dangerous as Bech’s own once youthful foray with a friend over comic-book frames (please see the matchless passage quoted below in full because it is memorable enough to make quoting it at all as much a waste of time as Bech’s mission itself when a quick encounter with the target Romanian writer in this cultural exchange was just a simple statement from one of them, viz: “La Bourgeoisie.”) Not forgetting the mania of Bech’s own ‘phantom gears’ and the pedals he pushed into the floor as a desperate backseat driver, the real driver twiddling his horn at the front. And not forgetting the large wristwatches, and much else, and, yes, the ‘Tveest’: “Chubby Checker bubbled from the walls.”

“In bed, when his room had stopped the gentle swaying motion with which it had greeted his entrance, he remembered the driver, and the man’s neatly combed death-gray face seemed the face of everything foul, stale, stupid, and uncontrollable in the world. He had seen that tight tic of a smile before. Where? He remembered. West 86th Street, coming back from Riverside Park, Mickey Schwartz, a child with whom he always argued, and was always right, and always lost. Their ugliest quarrel had concerned comic strips, whether or not the artist—Segar, say, who drew Popeye, or Harold Gray of Little Orphan Annie—whether or not the artist, in duplicating the faces from panel to panel, day after day, traced them. Bech had maintained, obviously, not. Mickey had insisted that some mechanical process had to be used. Bech tried to explain that it was not such a difficult feat, that just as a person’s handwriting is always the same—Mickey, his face clouding, said it wasn’t possible. Bech explained, what he saw so clearly, that everything was possible for human beings with a little training and talent, that the ease and variation of each panel proved his point. Just learn to look, you dummy. Mickey’s face had become totally closed, with a pig-eyed density quite inhuman, as it steadily shook “No, no, no,” and Bech, becoming frightened and furious, tried to behead the other boy with his fists, and the boy in turn pinned him and pressed his face into the bitter grit of pebbles and glass that coated the cement passageway between two apartment buildings. These unswept jagged bits, a kind of city topsoil, had enlarged under his eyes, and this experience, the magnification amidst pain of those negligible mineral flecks, had formed, perhaps, a vision.”

My recent review of Updike’s THE WAIT: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2022/07/15/the-wait-by-john-updike/

OUR WIFE by V.S. Pritchett

“Even her little eyes are noisy.”

A man’s hilarious and Huguenot haunting narration of inheriting his wife from Jack (a poet) after the latter died, a short woman’s personality larger than life, perhaps even larger by personality than Jack’s heavy Huguenot wardrobe with opening door every time she and the narrator get into bed together thereafter, a woman bent to take men away from their boats by making loud comments about them in pubs, so eventually the narrator leaves her in his will to someone called Trevor!

My previous reviews of VSP: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2020/02/11/essential-stories-v-s-pritchett/ and https://elizabethbowensite.wordpress.com/2022/05/30/v-s-pritchett-the-camberwell-beauty/

THE AGENT by Gabriel Josipovici

“He bought an apple and went back to his room.”

This is a story in two halves that like MOBIUS THE STRIPPER by the same author above needs joining up, like the papers in the story itself, to make sense of the espionage and disguise things going on, a sort of palimpsest of two cities in England and Geneva, as it were, if I am not mistaken.

For someone else. To whose railway station locker of secrets I may have lost the key.

THE EDITOR REGRETS by V.S. Pritchett

“I waited for my Liberator

He shall not escape me.”

Is this long lost Pritchett? If not, it should be! The dated story of celebratory editor Macaulay Drood, with a painted portrait of himself, once displayed in the Royal Academy, on his office wall, said by some to be unworthy of him, just as is the Guatemalan woman’s outrageous rag doll from her childhood unworthy of her, planted in the bed in his room at a European hotel, a series of conference hotels, as she stalks him across Europe with her poems and idolisation of him, and her contention that the worst apartheid is the one against women… waves of her voice, and a hissing kiss, and the ‘mass face’ of the conference audiences he ever faced, not individual faces, and just think of marital desertions and family diasporas at crises such as the Cuban one at the time of this story, or Covid recently! This is full of much Pritchett prose magic and absurdist strength, a positive that is made unworthy by the real dangerous madness it conveys. Or is it a synergy that still works to destroy what is unworthy in us all, each with a mass face or not? (I hear the Guatemalan woman’s father murdered her mother because she dyed her hair!)

THE SPECIAL PAIR by Maggie Ross

“Boredom was the worst enemy: they ran from it as from the devil…”

Even from each other as a pair of devilish fiends in the Uffizi alongside Botticelli, or Les Enfants Terribles by Cocteau, or a piece of music by Vivaldi, or, I guess, a story by Mary Butts. The incredibly dense portrait of a ‘married’ couple who are in intense mutual synergy, often not mutual, seeming identical to outsiders, but each of them inviting ghostly catalysts into their lives, as if catalytic Bowenesque shadowy-thirds, first a girl for him, then a man for her. This is not a story as such, but a study in — or a sonata by — dopplegängers for each other, this male reader as catalytic intruder, even the female author, too?

Cross-referenced with THE HOUSE PARTY by Mary Butts: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2022/08/31/the-house-party-by-mary-butts/

SOIR DE FÊTE by Ruth Fainlight

“…smelling the drink on their breaths. Then she [Ann] was distracted by a sound like a piece of silk being violently ripped, and forgot them. The first firework had gone up.”

…the perfect analogy for a firework, starting the process of disintegration in this effectively disturbing shadowy-third story, Charles and Betty having befriended Ann as their own third, or ‘trois’, in this town and its French carnival, with the telling theatrical prop earlier of a pearl necklace in the shared apartment into which they had invited Ann to stay, and outside with much body-choking confetti and some likely lads following Ann and Betty when Charles was separated from them. But later on, as they drink on the beach as a ‘trois’, the final disintegration is triggered, not by Charles himself, but by his elbow…

“Before considering what he was doing, Charles crashed her [Ann] down with a blow from his elbow.”

PROPERTY by Penelope Gilliatt

“PEG lies on elbow with her back to him, watching MAX.”

I can’t bear reading plays, even plays written as stories, or stories written as plays, and whether allegorical or not, but I did spot the above stage direction at outset, before giving up and dredging this summary from 1970 that is shown on the internet, in the hope it may assist you…

“Short story in form of allegorical play with three characters – Max, Peg & Abberley. During the entire three scenes of the play they are on stage, confined to their individual beds by wires attached to three electrocardiographs at the foot of their respective beds. A separate spotlight is trained on each bed. When a character goes to sleep or withdraws from contact, his spotlight snaps off. At the beginning, Peg & Abberley are married, but Peg has fallen in love with Max & asks for a divorce – unhappily, Abberley agrees. In the second scene, Peg & Max are married & the scene involves a discussion between Max & Abberley of Peg, the previous & the present marriage. In the third scene, Abberley criticizes Max for not taking proper care of Peg as he had, while Max tries to explain that it is simply the result of time & age & Peg attempts to restore some of the earlier warmth with Abberley.“

TOO MUCH TROUBLE by Kingsley Amis

“But few of us would have the self-command necessary to keep us at the top of our tippling form in 2022.”

Featuring various acronyms like TARDIS, such as TIOPEPE (Temporal Integrator, Ordinal Predictor and Electronic Projection Equipment), this is an extraordinary time travel story involving Simpson’s research into future drinks and pub habits involving the period, say, of an elongated Easter, and, inter alia, about the general ethos of ‘too much trouble’, and all the burnable rubbish taken to ‘Coulsdon dump’ (where I myself lived for all of the 1980s and early 1990s!)

It is a story published in 1972, set in 1975, and including Simpson’s time foray to 1983 where nobody could get even their broken leg mended during the Slack. And about paradoxes of a self meeting the same self out of time. (Simpson returns to his home time beaten up but safe, it seems.)

Factoring this story creatively into some of our own proclivities today is a revelation! But what is the implication of the El Minya Whites and Jerusalem, Israel? Beats me.

***

Publication context here: https://etepsed.wordpress.com/1377-2/

Illustrated version of above review: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2022/09/07/too-much-trouble-1972-by-kingsley-amis/

My Coulsdon stories of yore… https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2021/09/17/clockhouse-mount/

FINKEL by Jay Neugeboren

“Professor Perlman nodded, smiled weakly and tried to pass, but Finkel stopped him, grasping his arm above the elbow.”

A nightmarish tranche of earlier twentieth century concerns, showing that every age has its own nightmares and bigoted meaninglessness as derived from its changing gestalt of human fallibility. At least it was ‘above’ the elbow, perhaps allowing symbolically the ageing Jewish Professor, at the end, a seeming loophole to escape from Finkel, Finkel being the officious, over-talkative keeper of the apartments to which the Professor has moved, Finkel who, with his cancerous dog Sasha, claims he himself is Jewish but also an ex SS Officer, with much talk about the equally cancerous Freud. Finkel who, till the end, when his dog is dead, rancorously keeps the local chalking kids in order! The apartment where the professor can hear, through a grating in his toilet, a young couple next door, two of his students, descending into sexual violence. The professor whose own daughter’s boy friend had been one of his students, the subject of study being, as if accidentally touching base with UK readers like me today, “Eros, Entropy and the Elizabethans.”

THE EXPATRIATES by Ruth Fainlight

“…glad he had escaped, even if only for a short respite, the terrifying and exhausting necessity to be mad.”

The necessity of insanity, Dick once almost shooting himself and his wife Jeanette because they were happy, so what else could they hope for? This well-written story about Juliette’s sad, declining life with alcohol and cigarettes and her husband Dick (sporadically under the ‘practicante’ at the clinic for madness) as expatriates on the Mediterranean, striving in the tourist bar business, but gradually swindled by business partner Joe and even by her own lover Max, who is in currency cahoots with Joe. What else can be said about it? Nothing. It is as good as it can be. Or bad.

MAN AND DAUGHTER IN THE COLD by John Updike

“As a child he had imagined death as something attacking from outside, but now he knew that it was carried within; we nurse it for years, and it grows.”

This is the powerfully mind-insinuating portrait of Ethan and his 13 year old daughter Becky, and his two younger twin sons who need help with their laces… and he sees Becky as a growing woman for the first time, as she out-skis him, as he grapples with his asthma inhalator, and they go alone together foolhardily to the frostbitten top…. and the resultant rite of passage deploys feelings that are inexpressible and inexpressibly you absorb them. This art of fiction is one degree or two below numb osmosis, but you come out if it, when warming up, knowing much more than you did before undergoing the trip.

DEAR ILLUSION (1972) by Kingsley Amis

Potter, an ageing man who made it enough as a then modern poet to receive a visit from a female journalist and a male photographer to interview him. A satire on then modern poetry, indeed, and the various types of luminaries who sucked up to it, with the biggest off-the-cuff (slipped almost imperceptibly out of context) obscene come-on from a man to a woman into any otherwise polite or business-like conversation between them! And later he issues a new collection of his poetry called OFF! Not to mention the corned beef hash. Full of avant garde and traditional poetic spontaneities he wrote in one day now acclaimed at a launch ceremony, followed by his finest act of all. One thing the story did not explain (or perhaps had hidden within it without realising it was there!) — whether Potter’s wife had written all his previous poetry on which his reputation was based!

A poignant story about the angst of creative writers (often needing medication), as well as a story that is a fucking hilarious hoot and a half.

TEMPS PERDI by Jean Rhys

“But why be glad? Above all, why be sad? Death brings us its own anaesthetic, or so they say . . .”

This is a complex story that one wallows in without worrying about the complexity, not Proustian as such but more about time wasted rather than time lost or regained because why not? A threnody upon the 20th century between the wars and in the second war through the eyes of a woman billeted in an English house near soldiers, and thinking of Vienna in her past with the texture of clothes and people, and high trapezes elsewhere and a sword dance and young pretty girls Japanese or Carib or…those people of such nations … Carib history….and a prophecy of the French and English arguing…. with, I guess, this story’s reference to “vulgar, trivial lies.”

LA BRUTTA VERITÀ by Brian Glanville

“You turn aesthetics upside down, what’s ugly becomes beautiful. So you get pop art and welded sculpture, because you’ve given in.”

That’s the view of a middle-aged artist working in the tradition of Renaissance sculptures, a man called Milton living in Florence, teaching art to pretty ‘chicks’ one of whom he gets off with, much to his own guilt about his wife Beth. A story about the tension between reactionary art and modern art, cast in an effective written work itself in tension between a traditional and modern style when it was published in 1972. A work in various styles of, say, streaming conscious and of crafted word order. Characters believable, genius-loci evocative, and Milton’s own unresolved doubt about what he should do next with regard to his future, his artistic and personal future, reflects the tension of the written work itself and the styles of art it pits against each other.

Some readers consider Milton’s Satan to be the hero, or protagonist, because he struggles to overcome his own doubts and weaknesses…

God of the Renaissance versus Satan’s corruption of Art?

Football the religion of the Masses? The Ugly Truth.

A photo I took about an hour after writing above review! —

This review continues from here: https://nullimmortalis.wordpress.com/26968-2/