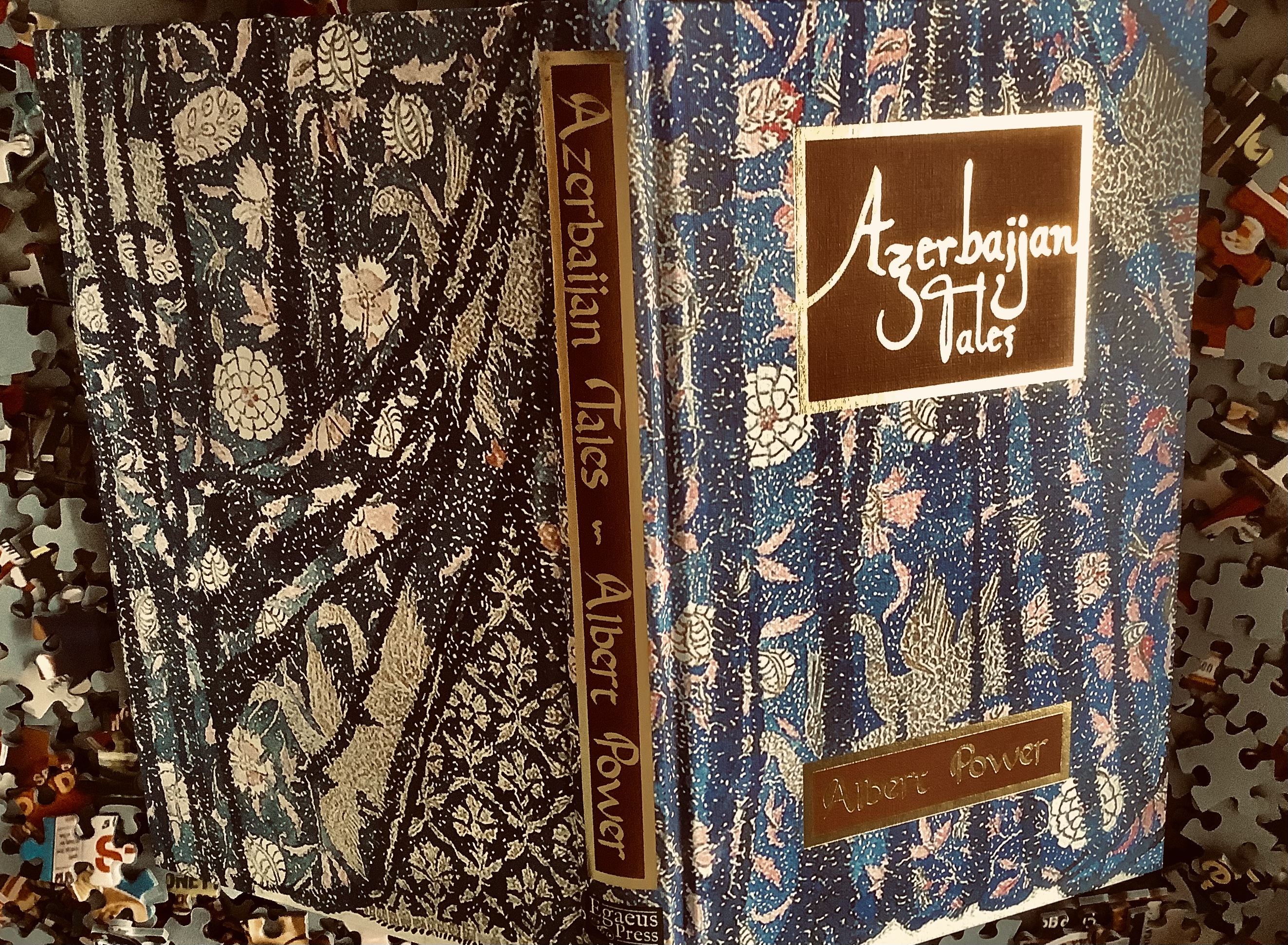

Azerbaijan Tales by Albert Power

My previous reviews of Albert Power: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/29098-2/and of this publisher: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/tag/egaeus-press/

When I read this book, my thoughts will appear in the comment stream below…

This a beautifully designed book in all respects, with over 250 pages…

The first work MATINEE IN BAKU I believe may have been revised for this mighty overall collection of otherwise new works and, of course, the first work may now be even more effective than how I thought of it originally!

However, as a result of this being the twilight of my years, I have long had a normal rule that my real-time reviews of particular works are what they are, when they are…

…and the first one below was first reviewed by me here: https://nullimmortalis.wordpress.com/2010/12/04/mad-matinee-in-baku-by-albert-power/ in 2010, and my review was written in separate real-time sections, in the context of the book that then published the Power work — as follows…

===========================

‘Mad Matinée in Baku’

… there are two quotes, one from Mikhail Bulgakov and the other by Horace Walpole.

Normally, I start each section of any particular real-time review with, in italics, what I instinctively consider to be a key quotation from the text, key in the sense that it is both personal to me as well as relevant to an ignition of any reader’s engagement with the book as a separate entity from that reader or from any fallacious considerations of Intention.

Writing a real-time review is a special reading-journey on the internet – a journey that takes place within a single reading mind, beset by all the foibles of the moment. The question is: does this affect the journey itself, i.e knowing one is publicly describing that journey as it happens?

***

“The self-superannuated film actress took a sip from her tall glass of cinnamon-scented tea and winced.”

The style is tea-stained Proustian, exquisite, forcing the reader to pause, sip, savour, shudder with joy simply at the language and proceed with due care and attention. Here we have a well-characterised, once famous but now post-maturing, lost-in-the-crowd, Azerbaijan film actress with an Armenian name meeting someone surprisingly older than herself in a Baku teashop: he calls himself a ‘Brother’ from Dublin. The location entails she can’t order her own drink, being female…

I cannot, shall not, from this point, continue describing the plot (as it unfolds in real-time for me), but I shall describe my impressions, hoping to entice you into buying this book, as not only my first impressions but also my already enduring, unshakeable impressions inform me that you will love owning and reading this book, but especially if you can appreciate someone like me telling you about my journey through it. (4 Dec 10)

***

“In 1962, I was a girl. Only a girl.”

Apparently, the ‘Brother’, amid today’s tea scents, is interested in an unremembered live play in which our actress took part in 1962. [I am reminded here, without feasible connection, meanwhile, of the fiction of Frances Oliver.] (4 Dec 10 – two hours later)

***

I learn elsewhere, significantly for me and for my previous Power review, that Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto was first published on Christmas Eve. And we learn in this book that Walpole’s The Mysterious Mother (about incest) was the play arguably featuring in 1962 a very young actress who is now so far the main protagonist in this book … in a Baku teashop. But I wasn’t intending to re-narrate the plot, was I? This book itself and its wonderfully textured text absolves me of any spoilers I may inadvertently divulge, I hope. (4 Dec 10 – another 2 hours later)

***

“Guilty until proven innocent: this was the way it had become with religious orders in Ireland, averred the elderly brother bitterly.”

The side-business of the teashop (parallel with my own buzzing preoccupations regarding my daily life as I read literature) provides backdrop to an intense discussion between the Actress and the Brother. In spite or because of the multi-faceted diamond prose in which it is expressed, the ‘inquisitive’ nature of the intensity of reminiscence in 2010 of 1962 is genuinely compulsive to read-in-regression about possible abuse as I reach a genuine cliffhanger at the end of the first main section partitioned in the book’s text, as opposed to my arbitrary page number references. As crisply page-turning as a thriller, but also as long-lingeringly savourable as a work of close-ordered poetry. All complemented by the book’s design itself. (4 Dec 10 – another 3 hours later)

***

“…and be the year of such scintillant sunshine 1962 or even 2010.”

I am intrigued by my seemingly unshakeable memory of the black-&-white Fifties and Sixties, while it is only artful literature that is able to shake me back to the real golden suns that must have existed in those days. And, without giving too much away, the story itself is now in (retrocausal?) ‘regression’ [in this book’s crime-mystery-fiction-of-what-happened-back-then-and-who-did-it? (my expression)] in a similar time-shaking fashion, i.e. back to that performance of the Horace Walpole incest play (rarely performed in England let alone under the Communist skies in the elsewhere of 1962). And back to its medicative incidental music to replace textual longueurs in the play…? By Aram Khachaturian’s onedin or Rheinhold Glière’s glorious Symphony 3? (A clue – this book’s printed dedication is ‘in appreciation of the music’ of the former). (5 Dec 10)

***

“But her touch was iceberg cold…”

History and rape sweep back into geography’s politics amid this furthering-back in a (temporary?) plot-foreshadowing regression to 1948 (the year I was born), and a love/hate panoply that is truly affecting. Prose-style-to-work-hard-at-yet-to-die-for together with a thrilling page-turning immediacy and high narrative power. Only truly special writers can do this. (5 Dec 10 – another hour later)

***

“Whatever was afoot, whether integral to the performance or disruptive of it, the spectacle taking place in the auditorium occasioned her no small amusement.”

Which is parallel to my enjoyment of this book in the last few pages. From serious rapine and fateful incestuous parthenogeneses of history in the past’s past, I reach here an Udolpho-Vathek Theatre of the Absurd, where audience and play reach their own incestuous pitch of verbal slapstick… I am both crying and laughing. If not in actual fact, certainly in inclination of literary experience. I fear, throughout, however, for our young heroine’s inevitable audit trail of life as seen to be in the process of being mapped out by this book. Especialy as there is nothing I can do about it. (5 Dec 10 – another 90 minutes later)

***

I am beginning to realise this is indeed a very clever book. The slow but paradoxically rushed rushdie russonance of religions (including the catholic frailties of abuse) and magicial realities beyond Magic Realism and politics and azuzbek cyrrilics &c &c of language intertwining — but, for the 21st century reader’s health and safety to resist the brilliantly described, pre-yielded-to temptations of concupiscence, I’d advise – in the running-fast, yet slowly-textured, text – the overall caveat of Maturin’s tenet that “Terror has no diary.” Trust in the reviewer. You see, I’m soon to have read the whole book. You haven’t read any of it. (5 Dec 10 – another hour later)

***

“But Marinitsa was being rushed headlong forwards so fast that she couldn’t even see,”

I think I have already said what I need to say about this reading experience even though I had not (until now) read the last 20 pages or so. It’s not that I predicted the end. I didn’t. But it sort of predicted me and my earlier words. I feel privileged to have been able to read this cross-religious, visionary, exegetic masterpiece. Pity only a 100 of us will be thus privileged. (5 Dec 10 – another 90 minutes later)

END

And the culprit, he was Spartacus.

THE PIT-CRYPTS OF KISH

Pages 95-104

“…and thinking: thinking such as his sort think, if it can be called thinking.”

As we all do, ‘her sort’, too, thinking variable truths. From ‘wingnut’ to the variable position of Albania and other shifting peoples or religions in Azerbaijan history (a history partly deployed in these first few pages of this novella), thoughts as thought or actually spoken out by variable characters at an archaeological dig of Military Antiquities in 1969, under the sway of the controlling minders of Sovietism, here one particular male minder. Another character digging is a young outspoken woman, Anush.

I am already captivated by the priceless prose style of this author, the characterisation, and what truth might be thought up next or militated against, whatever the power of revealed monument or antiquity.

Pages 104 – 111

“In the case of Anush such thoughts as came formed a warren of unworn-away worries…”

This is so utterly prose-powerful, idiosyncratically constructive in its semantic and phonetic decorations, one can almost miss out on its plot nested within a seeming warren as potential gestalt. And I need not worry, equally worn and unworn as I am into its clinging texture of words as dug lands, as you shall be, too, if you persist alongside me.

We indeed accrete more of Anush’s sometimes cruelly felt backstory of mixed feelings, and of the land’s history, religious and political, surrounding it, Albania and Armenia, for example, as moveable lands of thought in synergy or opposition, while we simply rattle along in counterpoint upon such a moveable land, Anush and the others being in a car — currently minder-free, or are they? One of them may be a spy? A message for our own times and lands, perhaps.

“I think you’re likely right, Anush; but it’s not always wise in these times to be right and say so.”

Pages 111 – 121

“…an oblong of many arches, symphony in turquoise, mauve and brown…”

…from that to the “melody lines of a symphony” that a composer may make of 39 year old Anush’s own facial expressiveness. And this wonderful genius loci, spirit of place, call it what you will, this land where Muslim meets Christian, its architectural spirit, its spiritual one, too, as Anush returns to her different form of ‘digs’, staying with a friendly Muslim couple, and we gain the sense of a spirit of interior place, too, the homes inside as well as the outer buildings. And Anush in her bedroom senses both the scent of the Mosque as well as an undercurrent of incense, following such scent’s coterminous connection with the conversation she had with the woman of the house before they retired for the night. And, then, the recurrent, covivid nightmare that Anush endures about her past lover, but now with added elements she had not dreamt before. If you read the matchless prose of these pages you will gain far more meaning as well as trepidation than I can convey to you here, or more than I can ever convey because I am perhaps not able to convey them properly to myself.

“Was it a soul-ache for some sort of dribbled compensation from the Almighty: to seek the cold consolings of a faith seeped to his people by her God…”

And I have not even yet touched upon what happened to the River Kish in 1772.

Pingback: Between Digs | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time Reviews Edit

Pages 122 – 126

“…the steady and inexorable tick-tock, tick-tock of the big grandfather clock in the corridor outside, monitor of mortality.”

This book makes me doubt conspiracy as well as apparent candour in such a political climate, a politics that involves religion as well as the strictures of the state. Who can we trust? Can we trust this book’s protagonism of Anush herself, a doubt I suddenly felt when granted a glimpse here of another character’s point of view of her giving a “filly-free toss of the jaw.”

Can we trust indeed this apparent freehold author himself, who may indeed be as unreliable as another conceivable book’s ‘unreliable narrator’ device amidst any leasehold techniques of its narrative pecking-order? Can I even trust myself as reader?

Pages 126 – 137

“‘Our Soviet state does not allow such things — as ghosts.’”

…as heard by Anush years ago.

I do trust her, whatever I may have thought yesterday, and I follow her, although I am not the one she imagines with binoculars or stalking her into (justified?) paranoia, yes, I follow her amid her new seemingly enforced ‘sick-leave’ from her digging job, amid early morning, with various scents and fruits being sold, and later, in a Holy Qur’an, itself half-hidden in a drawer in her lodging digs, she finds a pamphlet (nested like a Catholic Church within the Mezquita of Córdoba?) (or like Satan as a serpent in Eden?) about an old Christian (now disused) chapel in a nearby village called Kish (a building looking like “a squat-bodied insecticide gun aimed up”) and I imagine her, perhaps wrongly, as if about to enter her own version of a M.R. James story when visiting this church during her new-found leisure time, as surely she is destined to do, amid all the (imagined?) conspiracies and spies around her…although she may not be the prime target among her erstwhile fellow diggers. Meanwhile, I need not continue repeating mention of this book’s elegantly, sometimes idiosyncratically, evocative descriptions of genius loci as places and of books, food, beverages and individually precarious people… and you must take these literary assets as read, while you yourself follow (or even stalk by lurking!) my future reading of this particular novella, indeed of this whole book.

Pages 137 – 144

“A kaleidoscope of worries swirled within the harried fancy of Anush.”

Anush is worried about being surveyed by a ‘shark’, as she — our trusty protagonist who ironically does not trust herself (“Was it because she was unworthy?” etc) with a ‘digging-devil voice’, and also harbouring religious doubts despite her faith in a Christian God — follows her own short, state-allowed trek to the pamphlet’s church or chapel, walking past “a huddle of habitaunces”, as if the disused, deconsecrated church actually expected and awaited her.

A sense of its eventual interior — I felt it alongside this new version of an M.R. James ecclesiastical explorer (usually male) now our heroine but with dithering confused balance as she sees a tricorn design within a chandelier, as if of “crouching foetuses”—

Only with books couched like this book can the reader be a trepidatious explorer, too. No spoilers intended, just a companion traveller.

Pages 144 – 152

“‘Absorbing the sacred aura’—“

…as I do, too, regarding the text’s words, whatever the scatological pit-crypting of her shadowing shark by dint of making her own “tuft-enticement out-thrust”…the Anush bush, as it were? The ‘hot bitch’, rampant against the one who called her that.

This is not M.R. James at all, but something even more powerful, the faith of a woman and her means of attack, as the derelict church (itself regaining God’s soul that was once within it) almost mocks her, then irks her, inspires her, with its holy hollows below, into an equivalent righteous raping of a man, not by him. A catharsis and purging of her past? Hunter and quarry. Intrinsic subtle or plain faith in her God and the blatant instinct of revenge. Whatever the case, this High Noon — of two duellists within this church and all that the church and the land’s hinterland of history entail — is played out in possibly the most powerful tranche of fiction one is privileged to read. Beyond the battlefield’s trench of the reader’s own mind.

Above scene is now significantly CROSS-referenced with that in pages 137-139 here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2020/04/17/witch-cult-abbey-mark-samuels/#comment-22615

Pingback: Synchronicity rampant… | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time ReviewsEdit

Pingback: Hunter and Quarry | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time Reviews Edit

Pages 152 – 164

“BAM—BAM—BAM—BAM. BAM—BAM—BAM—BAM.”

An ominous tolling of knocks of what has been released from the pit-crypts and allowed to roam the Earth as a monster of Hell or politics.

But equally, yes, M. R. James, after all, I guess, with forces released from church meddlers, but, it is now possibly more like Robert Aickman — with my having very recently, and with disturbing convenience, reviewed (HERE) his rare masterpiece of a story entitled ‘The Breakthrough’ where the floor of a church is somehow BAMMED open with comparable results!

What Anush brings back with her to her digs is, however, mingled with a purging nod toward the ‘Apostle of Tarsus’ (Cf Saul as the actual name of the main protagonist of the Samuels book that I referenced above yesterday!) and to the “Pieta-like pose” of those innocents thus purged. A most satisfying and spiritually enhancing finale to this novella that I will not clarify further because any innocent readers need to read it first without full prior knowledge of what lies in store for them.

THE SANATORIUM AT CHAKHIRSHIRINCELO

Pages 165 – 167

The scene is set and I am already captivated, and not only because I am already a lover of sanatorium plots as written by great writers ever since my first youthful reading of Mann’s Magic Mountain and my later reading of John Cowper Powys’s The Inmates and Aickman’s Into The Wood…

This one is situated in a sanatorium for those suffering with their mental health under the sway of the ‘Supreme Soviet’ in 1968, and we are introduced to an intriguing character of middle-aged Dr Yevegeny Bondarchenko and his ‘annexe’ of an office like a prow of a ship nested in a building in the land contiguous to Iran as gouged within a similar cleft as the annexe, I infer. The Power descriptions of the Soviet influence on nomenclature and on the chosen geography of the awesome place itself cannot be done justice here. Just to mention that I happened to read a short book yesterday (here) entitled ‘Annex / Anexo’ and I have already felt an initial frisson of possibly unintentional thematic connection…or cross-section?

nullimmortalis August 8, 2021 at 8:46 am Edit

This review now continues here: https://elizabethbowensite.wordpress.com/albert-power/