Witch-Cult Abbey – Mark Samuels

ZAGAVA MMXX

My previous reviews of Mark Samuels here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/mark-samuels/ and of this publisher here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/zagava/

When I read this book, Covfefe permitting, my thoughts will appear in the comment stream below…

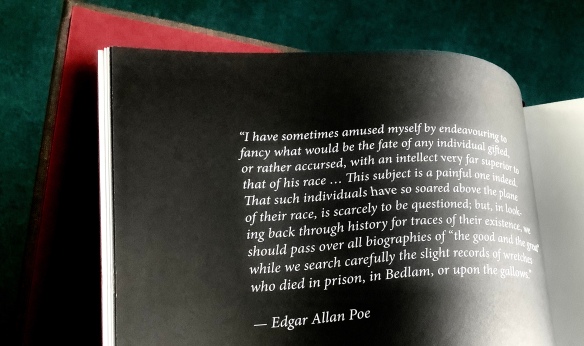

This is a hefty stylish book, 12 by 8 inches, with stiff luxurious white printed pages, interspersed with numerous black divider pages, some generously decorated, between each chapter. Some of these black pages bear quoted extracts from famous authors. My edition is numbered 50/199 and has around 190 pages.

My first gestalt real-time review in 2008 was of a Mark Samuels book. At my advanced age and in current times of Covfefe, I am determined not to finish my review of this book until I am on the point of death.

.

Chapter One

“My sole purpose, it seemed, was to hibernate until this outbreak of leprous ideologies had played itself out across the European continent.”

An engaging, often evocatively detailed, account of a narrator who is referred to, by other characters, as Mr Prior, and who refers to himself as a “half-cripple”, living during the Second World War, with the status of a guest, in a Cockney family, a London beset by air raids and nightly resorts to Anderson Shelters. Much to the sadness of his hosts, he is unexpectedly given a trial job — by dint of a previous position he once held — as a library cataloguer at Thool Abbey in Hertfordshire … and he travels there by train, an Abbey that sounds as if it had once too easily relinquished its Romishness to the sway of Henry VIII and that king’s scions.

TO BE CONTINUED IN DUE COURSE

My cross-reference to A LITTLE LIGHT READING as an attempt to reconcile my almost permanent suspension (as a failsafe) of this Samuels review: https://elizabethbowensite.wordpress.com/robert-shearman/#comment-1103

Please also see top bold comment above for erstwhile context.

And a few minutes later, since writing above, I found myself writing this here! https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2020/07/10/survivor-song-paul-tremblay/#comment-19494

Chapter 2

“What has blocked out the daylight? Is it the work of Germany?”

This reminds me of my very recent review of this author’s Posterity here? Was it Gallows Langley Station there, too, nearer into our present than the Second World War here and air raid blackouts in this book? I forget. Well, whatever the case, I do forget, but I ask — do I meet Lady Degabaston here at Thool Abbey after a night of nightmares, a night still prevailing? If so, this Samuels female character it is quite an introduction to, an Edith Sitwell sort, perhaps, with my having been made to stay, with my useless fob-watch, overnight without being interviewed for the bookish work first, and provided with a gentleman’s travelling kit: an array of stuff to make up for the fact that I did not have any suitcase with me.

I am more enthralled than I expected to be, so I will persist with this sporadic reading till I finish it.

“‘Do the dead speak a language whose meaning contains all possible meanings since their mode of being is outside space and time?’

It appeared to be nothing more than a book of gibberish, and I replaced it on the shelf.”

I shall sooner rather than later find out the answer to that italicised question, possibly, as the health condition that struck me in 2015 (and was hopefully dealt with at that time) has unfortunately returned and spread in recent months. Hence, my very gradual resumption of this last review, although some proposed treatment may help me.

Graveyard-worm leeches are maybe more efficacious, having now read the start of the next chapter below!

Pages 47 -53

“The laboured incremental advance was taking an even greater toll on my nerves.”

I have been dabbling recently in much of that gluey Zenoism (‘incremental’ as in Zeno’s Paradox), especially while reviewing Aickman’s Fontana Great Ghost Stories series in detail, and also Samuels’ own ‘Posterity’ as the woman narrator there, like the male one here, also gets bogged down in trying to escape from somewhere.

Now he’s suddenly back at the Abbey being tended to by a doctor, an old man who looks my age; there the similarity ends, I contend!

Pages that are stubbornly, insidiously gluey with benightedness, and his trying to control what he deems is his own dream, one that possibly turns out not to be his dream at all, and other shapes and figures with dark catchphrases, including the Degabaston woman who invited him here.

Leeched by graveyard-worms. Fulsomely nightmarish. But for what purpose of paranoia? Or purely for disturbing others who are looking in by means of these words being read? Do those others want to be thus disturbed by what they read, and, if so, is it successful in so doing this?

Pages 53 – 59

“ I felt somehow permanently enervated, not through an outside force, but rather due to a decay in my own internal powers; the type of enervation that comes only with advancing age. Could a few days spent within the abbey correspond to a span of years spent in the outside world?”

Could it be happening to me spending my twilight period reading about this abbey? It may not be a nerve agent or mock gestapo forces or a strange time-immune moon or the wizened denizens of the abbey itself or even paranoia? — but I sense it is all these causing me to get confused, during another attempted escape, about the various forces attempting to keep me here to ‘catalogue’ this very book! Its various parodies of life and its other abominations. Should I sign up? Yes, I have already appended my signature on page 54, where indicated by an [X]. And I still do not know the nature of whatever has induced me to do so….

Chapter 4

Pages 65 – 71

Generally disturbing, I found, having recognised my own signature beside the [X]! — so it must be me the reader who is now contracted to fulfil the duties of Thool Abbey, being imprisoned by this very book written about it, and frightened by its denizens into efficiently cataloguing all the literally prehensile books in its library. Me, not him, as the narrator, as seen in the devious mirror of this book that it has inveigled me into reflecting upon. The act of my reading and reviewing now become an unruly game of chess between the book and its putative critic. My only respite closing it for as long as possible between readings…

https://vaultofevil.proboards.com/post/70059

Pingback: Cult or Fearless Faith? | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time Reviews Edit

Pages 71 – 75

“Still, Kruptos contaminates the understanding of all those who have read even some small part of the immeasurable whole:”

As the narrator continues to be constrained to fill the blank bibliography book and, eventually, he is caught up in the book mentioned above as written by a Thomas Ariel, as if its reader is always Caliban? Or something even worse? Diverted from straightforward cataloguing to absorbing!

The Kruptos book in many volumes, volumes that don’t start nor end, is said to create its own author — or, I ask, its own reader, even its own critic? — and this possibly sheds some crazy rationalisation on why I must have started, with this very author, my gestalt real-time reviewing project all those years ago!

Needless to say, I currently have a strong love-hate relationship with this author’s book. And with the potentially theosophical, literary and linguistic revelation of the book that this book now seems to contain.

Is the ‘witch-cult’ a symbol of what this author seemed to see as a cabal against himself some years ago? Genuinely not thought of that possibility till now.

Chapter Five

Pages 81-85

“…that damnable central book clutched to the bosom of the faceless witch-corpse;”

A chapter that starts with a telling quotation from Thomas De Quincey that tells me a lot more than I may have wished to be told. As a reader of this possibly self-damned book about a damned task involving other damned books — while trapped in a lockdown of endless night and self-tooth extraction which, in part at least, is only too reminiscent of our very recent past — I feel implicated, if not ‘contaminated’, as it itself says. Even without an explicit knowledge of the books that the protagonist is trying to by-pass for me by acts of omission or mis-cataloguing, something is seeping through to me nevertheless. And who, if not what, is Dr Cressop? Not annexed to one of those Ligottian doctors, such as Locrian, I trust.

The Abbey’s own annexe, meanwhile, has “…whispers like the wheezing of a last breath […] as its ancient structure settled as uneasily as the bones of a dying patient turned over in a hospital bed.” Marked to die?

Pages 85-89

I forget as I often forget these days, but is this the first time we learn that the narrator’s name is Saul Prior? A priory, if not an abbey? And surely it may be a spoiler to tell you any more about an apparent respite from night’s darkness at the time of the arrival of the Revd. Alphonsus Winters who seeks to enter what Saul believes to be the “madhouse” of this abbey.

This book has made a sudden turn for the worst or the best? Good or bad both in its events awaiting Saul and in its quality as fiction entertainment?

A page-turner whereby I somehow ever dread turning to its next page!

Chapter Six

Pages 95 – 99

“…is it not written in holy scripture that devils themselves will quote scripture to gain an advantage?”

…as this Godly author himself pretends to do or actually does?

And I am getting bemused by who or what is conspiring with whom or what against whom or what, by the difference between philosophical teleology and freakish teratology and by why we now seem to be invoking the name of Lilith Blake from ‘The White Hands.’

On the bright side, being thus bemused, even confused, is a sort of prophylactic for the reader against any insidious text, if indeed it is insidious? Equally, confusion can draw you in further than you would otherwise dare if you had clearly, if fallaciously, believed you understood the text’s intentions?

Pages 100 – 111

A ‘sin-steeped’ fictional device of info-dump represented by a long ‘verbal’ or verbalised ‘document’ as mission statement and backstory, representing Winters’ role in gaining entrance to the the Abbey for purposes of exorcising it (unless I misunderstand it). It is Gothickly couched in all manner of charnel unspeakabilities and conspiracies of lineage, ‘mad science’ and perceived hellish blasphemy to the one true Christian belief, and deploying, I guess, this book’s freeholder expression of views on religious and political European history as it affected, it is argued, England and this freeholder’s own personal victimised backstory regarding, inter alia, the leasehold distaff of our humanity — counterpointed by the spear of freehold self-literary references. Unless, again, I misunderstand it all.

A remarkable document in itself.

https://www.ligotti.net/showpost.php?p=1696&postcount=3

Pingback: Lilith Blake | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time Reviews Edit

Chapter 7

Pages 117 – 120

There are so many utterly blank as well as black pages in this book it makes it look thicker than it is. A parallel with the ever slow Zenoism of its time duration, inasmuch as Saul (the Soul who received a Road-to-Damascus?) fails to have noted that it is now 1948 (the year I was born) and the War is well and truly over as Winters now informs him, with the Socialists having defeated different Socialists. I am still on unsteady ground here as to who is good and who is bad in this now seemingly demented and attritional book. Perhaps none of us are wholly good or bad, but a necessarily optimal share of both? Or is Winters right when saying: “A grey neutrality of twilight cannot persist: one or other force must ultimately triumph.” But which one, I ask, as I riffle again through some pages without any writing on. Zeno would claim 4 minutes 33 seconds lasts forever? And blank stories are the only true meaningful ones? Aickman, if not Ligotti and Lovecraft, knew the answer, I claim — claiming this, as I do, from the depths of this also seemingly demented and attritional book review, a review mutually infecting — and infected by — a book equally demented and attritional!

See

“Here was a qualified Nothing, a Nothing of such deep despair, I could not be absolved of my aesthetic responsibility — a nonhope Nothing, a non-Nothing —“

a few days ago here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2021/07/28/a-non-nothing/

Pages 120 – 125

“The hunched figure of Lady Degabaston awaited us there, seated…”

…and indeed I called her earlier an Edith Sitwell type character!

But I will no longer taint her memory as a great poet with this comparison with Damnuels’ character. There are some incredible moments of horror and despair as Winters and his predecessor in exorcism are seen to have been or will be tortured even after death? I think the scene where Winters removes his gloves (were we told he was wearing gloves when we first met him?) and what then happens is probably — in its foregoing context and in its isolation as a single scene — one of the sheerest horror moments in all horror genre literature. And I do not say that lightly.

I am confident already that this book, however it subsequently pans out, deserves its honourable place HERE and thus it has been granted. The prehensile book in motion, one that I always predicted would come my way, and one that seems to morph itself between one reading and the next…

“…and it seemed to me that the architecture of the abbey had subsequently reorganised itself in a manner to baffle the unwary.”

Chapter Eight

Pages 130 – 135

“I could not be sure these thoughts were entirely my own.”

So what point this review of them? I need possibly long years of reflection, to answer that question.

Suffice to say, from the ascertainable, checkable quoting of Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius in white print upon black paper to the siren-call of Lilith Blake into the depths of her damnuelled tomb, I wonder if these pages represent an example of the now classic co-vivid nightmare: mixing real life and half-slumbrous visions that have become all so common in recent times, but I suspect this was all written down before such a concept became known to us all. Written before 2020, the year it was first published. I certainly hope, for various reasons selfish and selfless, that this unique and limited prehensile book does not morph itself into a mass paperback printed one. My edition is currently numbered 50/199 and if you subtract the first number from the second, the result is the long-term house number of someone whom this author once knew quite well.

A ‘Subtract’ – an apt terminology for this book itself?

Pages 135 – 137

“More than ever, I was conscious of being subject to the dreams of some irresistible outside agency or force.”

Another uncanny prophecy of what we all now know as the literally co-vivid dream.

And I feel I am myself exploring, as well as exploring myself, in this Pharaoh-like tomb of Lilith Blake — in this underground ‘tholos’? — a resting-place not surrounded by Egyptian treasures but strikingly by what we all know as… (a word, when in the singular, beginning and ending with the same consonantal sounds as those that begin and end Lilith’s surname.)

You see, I intend no spoilers; I am merely acting as a companion explorer.

Re ‘tholos’ — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beehive_tomb

Pages 137 – 139

What Saul sees in the pit-crypt is beyond words, but the author manages to convey what he sees of the buried Lilith Blake and what might be buried within the woman, whether dead or undead. It is another of those sheer horror scenes that, dare I say, does actually work well in this case. If ‘well’ is the right word!

More important, for me, perhaps, is another one of those synchronous synergies between two books that I happen, by chance, to be reading and real-time reviewing simultaneously. This one is possibly the most striking mutual synergy ever in my reviewing career so far. About half an hour ago, I read THIS scene in a Power book (pages 144-152), a scene which has now become the potentially exact spiritual or emotional or gender or historical inverse equivalent of this scene in the Samuels. The implications of such a contra-directional synergy to any of you who have read both books are literally manifold. If not womanifold!

Pingback: Synchronicity rampant… | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time ReviewsEdit

Pingback: Hunter and Quarry | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time Reviews Edit

Pages 139 – 141

In the Power book referenced above yesterday there is today an explicit mention of the ‘Apostle of Tarsus’ in the section I just read and reviewed earlier this morning and I think some self-assumed freehold creator of this Thool book now has his Road to Damascus as he experiences even worse nightmares beyond the initial worse-than-any-other nightmares, as if there is a freeholder beyond himself! His discrete and independent self now become a leasehold self? And yet another book is now referenced in this Thool book, a book explicitly called ‘The White Hands’ (the one that created Lilith Blake but now seen to be created by her?), a book that has in turn gradually entrammelled, and thus negatively transcended, his life as a would-be creator of his own books for posterity?

These few pages are utterly horrific — with no half-measures granted by Zeno now?

There is still a quarter of this Thool book yet to read, so perhaps all this will eventually be resolved for the better? To give it time for such a resolution to be fully completed, I shall now delay reading the final chapters at least for a while…

Cross-referenced here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2021/08/05/annexe-brian-evenson/#comment-22632

Chapter Nine

Pages 146 – 148

I may now resume my reading of this book but with even more gluey Zenoism, and I now note from De Quincey of the possibility of two brains of divergent badness or goodness, and the narrator’s own now antipathy to books themselves not only to the Thool library itself and any chuckling lectors beyond its currently locked door. (A sign of those two brains battling over various decisions — leading to and from this very book that has deterred me reading it for the last week or two, till today? The handleable beauty of books versus what they may contain?)

“…the sight of ink befouling blank pages was, to me, akin to the sight of decay or disease festering its way over unblemished skin.”

This review will continue here in due course: https://etepsed.wordpress.com/mark-samuels/