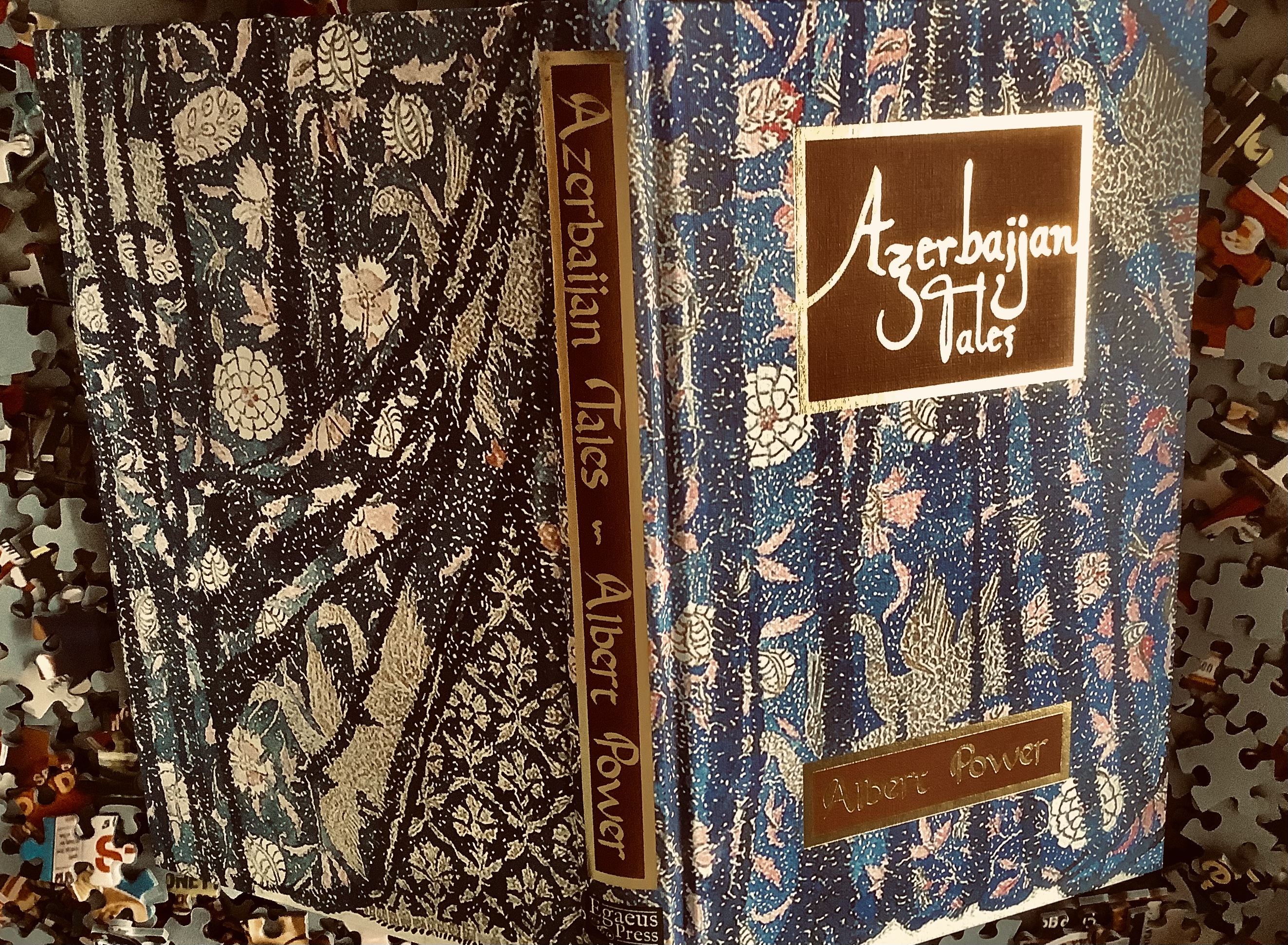

Azerbaijan Tales by Albert Power

Part Two of this review, as continued from here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2021/07/23/azerbaijan-tales-by-albert-power/

EGAEUS PRESS MMXXI

My previous reviews of Albert Power: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/29098-2/ and of this publisher: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/tag/egaeus-press/

When I read this book, my thoughts will appear in the comment stream below…

nullimmortalis August 7, 2021 at 8:44 am

THE SANATORIUM AT CHAKHIRSHIRINCELO

Pages 165 – 167

The scene is set and I am already captivated, and not only because I am already a lover of sanatorium plots as written by great writers ever since my first youthful reading of Mann’s Magic Mountain and my later reading of John Cowper Powys’s The Inmates and Aickman’s Into The Wood…

This one is situated in a sanatorium for those suffering with their mental health under the sway of the ‘Supreme Soviet’ in 1968, and we are introduced to an intriguing character of middle-aged Dr Yevegeny Bondarchenko and his ‘annexe’ of an office like a prow of a ship nested in a building in the land contiguous to Iran as gouged within a similar cleft as the annexe, I infer. The Power descriptions of the Soviet influence on nomenclature and on the chosen geography of the awesome place itself cannot be done justice here. Just to mention that I happened to read a short book yesterday (here) entitled ‘Annex / Anexo’ and I have already felt an initial frisson of possibly unintentional thematic connection…or cross-section?

Pages 168 – 178

To a new “dirty digging”…!

At least one thing of which I can be sure — you will never forget this initial meeting between Yevgeny and imposing and elegant and unmarried Lyudmilla Andereievna Parkostina, a Soviet official who has come to assess a woman patient’s possibly too early release. This patient’s anecdotal backstory involving aspersions of the Sapphic as well as of the murderous (akin to that earlier in the Kish work?)

And the implied reflection on our doctor hero, and his own mixed feelings about Lyudmilla herself as a woman, as he she imposes herself: at his own place instead of him, at the powerful position at the apex of the annexe window…

The build-up of characterisation and plot is uniquely Powerful. Each word punching above its weight within its context, such words as ‘helmed’ ‘river’ as a verb, ‘already’, ‘ice-crack’, ‘verge’, in fact almost every word! And I am only scratching the surface, even though many will think this review is already too long, no doubt.

This is one of those books to be hidden under my blotter, perhaps, when certain people visit me?

Pages 178 – 184

“He felt a pang as he took in the sight of that solitary ironwood.”

…being the sapling he once uprooted from the wet lands and replanted here with surprising subsequent growth of its boughs, much like, I infer, some of the romantic blank verse that he plants and uproots and plants and replants under his blotter. And this ironwood is where he sits silent near Tahira Karayeva (the ‘plaintive, pretty’ patient of whom I spoke above). He thinks of the comparative age gap in War and Peace. And you may infer what you like from what I thus eke out about this undoubtedly great Power work of literature, especially if you are accompanying my journey through it without also reading it first.

Not that, tantalisingly, I yet understand it all. If ever.

Pages 184 – 188

“Sunlight seemed not to be her element, though it adorned her.”

Without fear of being repetitive, I shall now repeat the mantra — ‘you will not forget’ … now, away from Yevgeny’s POV, it is this meeting between ‘mad’ Tahira and Lyudmila, the latter woman ostensibly (amid the “art in the bull-ring of adversarial inquiry”), inspecting the former — an almost (or even actual) tactile encounter between two individually beautiful women, as we feast upon the words, not eked out at all, that are used to describe the airs and graces that clothe their talking bodies. Yes, you will never forget. Meanwhile, I wondered before (and forgot to mention) whether Tahira’s erstwhile incident at the Pirembel cave is in anyway akin to the Marabar caves elsewhere in literature?

Cross-referenced here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2021/08/05/vastarien-literary-journal-vol-4-no-1/#comment-22669

Pages 189 – 193

“The dispensary where Tahira handed over at the counter the prescription drugs and powders that were got ready in a contained-off room behind, was at the far end of an annexe…”

Tahira’s POV now as we are perhaps led unreliably to believe the tale she tells to Lyudmila about the day she was stalked by that awful awful sensuous man (Cf Kish story) when seated by the Soviet patriotic monument (or am I being unreliable?) on her break from working at the dispensary to eat an egg and onion sandwich. Tahira’s own sensual self-awareness of language during our journey of her POV is quite dizzying with words. She is ‘seduced by her own musings’, it is suggested. As I am by my reading of them. As you will be, too. Better, however, to read the source words not someone else’s interpretation springing from them. Perhaps the purpose of any book review to entice reading of it is to posit thus?

Pages 193 – 202

“Worse a fate surely could in lieu befall […] Feint became woman and if feint was required . . .”

I spent most of the Nineties and Noughties writing, disseminating and, yes, self-gratifyingly reading my own works, after spending a lifetime before that, from the Fifties, reading mainly other writers dead and alive. This current period of the Tensies and Twenties so far represents hopefully my redemption by reading and disseminating the world’s great works — by utilising, in a passion of reading moments, whatever empirical power there is in my own words to express something permanent about these other writers’ works as an evolving gestalt, their works being greater far than my own works… but a redemption perhaps even more pretentious and self-gratifying than what it redeems?

And, perhaps more than most, this book is exponentially one of those great works.

This section is an amazing meeting of minds and bodies of two women, where we try to plumb their different and perhaps instinctively mutual motives by whatever unreliable or reliable source or POV that tells us about them in such a moving and beautifully wordy way. Two women that is almost its own unconscious troilism with tentigo, resonating platonic and otherwise. One to rescue whom from what? In this contiguity of Azerbaijan and Iran, annexed by a Soviet Supreme instead of God. But what of the man who sits by the ironwood tree?

Empirical perhaps, on my part, but even empiricism can be fallacious when interpreting books? And the recurrent metaphor of swimming in this section of Power’s pages reminds me that I have never been able to swim…

Pages 203 – 209

I now withdraw my assistance to the new reader for fear of spoilers. For fear, also, that any more assistance I should now proffer will be even more misleading than it may have been for past pages. Suffice to say, that I recall the writer’s name of Murad Pavelovsky from earlier in this novella, in connection with the papers Yevgeny hides under his blotter. And now some account that goes alongside a reference to Clark Ashton Smith who had died seven years earlier. Even a nod to Lovecraft, which as a word in itself rather than a person may be germane?

An account of four characters beyond mere troilism (characters including Tahira and Pavelovsky, but excluding Yevgeny and Lyudmila) who I have learnt to be crucial to this story now entering past events in 1968 of more symbolic Kish-like diggings? … no, not really, but more the once tentatively proffered Marabarness of Pirembel caves? Upon a new contiguous annexe with the Caspian and thus the fruit fields of Turkmenistan?

Caves, the entering of which is now Power-evoked at outset of entry, as accompanied by a fifth character in the shape of the caves’ curator, but also not without a reference to a Soviet woman composer, as one of these four characters (a woman I mentioned earlier above in contiguity with Tahira and my use of the word ‘Sapphic’?), a composer not unlike one of my favourites: Sofia Gubaidulina?

My previous review of the works of Clark Ashton Smith: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2014/08/30/the-dark-eidolon-and-other-fantasies-clark-ashton-smith/

Pingback: Oreto and Power | The Des Lewis Gestalt Real-Time Reviews

Pages 209 – 215

“An author is never done with striving to recall.”

I write real-time book reviews as just such a striving, and I am glad I am eking this novella out, slowing it down, in fact, just like the journey into the caves with these five crucially tension-triggerable characters who “dug steadily downwards into the innards of the earth”, deeper even than those digs in Kish, a “hypnotic” slowth as if an Aickman-like Zeno’s Paradox in a Jules Verne plot, twisting tortuously along “omnicircumferent” paths. Then there is that sound, not Rats in the Walls so much as a flutter or muffled mutter or nibble. Inspiring the music lover in me to be reminded of Janacek’s path and Tartini’s Trill with the explicit help of this wordy sound-fest of a text. The composer character, too, scratching staves on paper (as an echo of the sound?) to help record such a sound with music notes. The writer character looks on in a thoughtful recall of his own.

Why are these characters tension-triggerable, you ask? Well, you need to read this novella to discover such Mysterious Kôr.

Pages 215 – 219

“—ah, here was a trickier truth to catch.”

The cave system, and the erstwhile Marabar caves incident is perhaps about to be apotheosised by Pirembel, as the writer participant in it, already in what we thought the top gear of rarefied writing, reaches an even higher gear, perhaps the highest ever reached in literature, towards a new human evolution from caves instead of seas, and more through the “praeteroptic mind”, the projecting of a writer’s mind into the woman’s body standing next to him within such a cave system, and then watching the other woman composing into a notebook again, as we, too, as readers, embody the erstwhile “screaming and shrieking, squirming and struggling—“ and so much more that any reviewer cannot reveal. Cannot as well as should not. And if I cannot, who can?

Pages 219 – 227

“…it would be well to grease in time the choked chains of narrative.”

To grease my own speed of reading it, too?

But I am still sticking like a fly in aspic with the richly turned prose, as we gain more and more traction upon these five characters while digging, excavating, within the deepest lore within this book. Whether literary cloying or legends of severed heads and communities, far worse than today’s news of Taliban. that lived down here and now as “orgiastic savageries” infiltrating the sense conduits of the various characters. Including the apparent “ogling” by one upon another. But can women ogle women? Brutish men certainly can. Consuming skulls to the bone, “what might be perceived as the optical equivalent to the insidious whisper of chewing”, with the composer also sticky with “taking an inordinately long time to get down on paper the basic refrain of her rhythm…” An “aura of unease” and “unspeakable truth.” Human lovecraft as Lovecraft?

Pages 227 -233

“…snail-style to crawl by slow stages back up — […] …that mirksome burrow to eke out the yet more abysmal horror which hid within.”

A rare time where ‘abysmal’ is used in its full radiation of meaning. These pages are touched with madness, madness by its depicted characters as well as by the two leasehold or surrogate or collaborative authors called Yevgeny and Pavelovsky, but by its sole imputed freehold author himself and each reader alike, too!

I will not divulge details of this culmination of the cave system’s catharsis in case such details are spoilers or might also make potential readers fear for their own madness should they ever read this work, for me tantamount to word music as composed by both modern experimental and traditionally harmonic composers in spiritual collusion or collision. Logically, though, what would such filtered details say about this book review itself as written by someone who is reading it?

Pages 233 – 252

“What was the truth of the tunnel that narrowed to the girth of a pipette…”

I am astonishingly satisfied by this denouement, even though the mixed motives are still clearing and unclearing and clearing again and unclearing again, at the annexe points in 1968 with still shahful Iran — on a day today in my own real-time where Azerbaijan, if for no other reason, assonates, as a word, with Afghanistan, and thus connected to it by some tunnel of truth.

Mixed motives of lust, love or Leninism, Sapphic or otherwise, and the events retold by various means and reliabilities, the mixed madnesses, where even those we were most relying on become those we least rely on by dint of madness. And the reader flounders underground, too: even the most astute reviewer could be wrong, as Lovecraftian monsters enter for real my own life from time to time. I even interpreted the text under the blotter wrongly or I misremembered it and Yevgeny remembered it better than myself. I just KNOW he lived happily ever after with the woman from beside the ironwood tree. Yet you may know differently.

Whatever the case, I don’t think I ever read a work so beguiling and so full of surprising words. Not an “improbable farrago of macabrerie”, but something impossible that someone sanctioned as possible to print in a book by means of being on the nearest possible verge of truth. Yet, whether Verne or Forster, it (and much else) teeters on the edge of ‘TRAP’. And I myself was that doctor who was somehow seen with a monocle?

“There were, there had to be, more important things in life even than books…”

SIGH FOR A SONG UNSONG

A poem as perceivably poignant annexe to Tahira’s story.

Kish and tell.

“The spilth of ‘yes’ or pith of ‘nay’:

‘Be seeing you some other day.’”

end